Bijdragen en Mededelingen betreffende de Geschiedenis der Nederlanden. Deel 102

(1987)– [tijdschrift] Bijdragen en Mededeelingen van het Historisch Genootschap–

[pagina 229]

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Welvarend Holland

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

[pagina 230]

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Europa - met uitzondering van Antwerpen - voordeed’. This was the case both in 1535-1565 and again in the period 1575-1650 (172; see also 166). Holland's relative prosperity is affirmed by Noordegraaf, and his explanation for it is fully consistent with what I offered in 1974. ‘[Ik] acht’ writes Noordegraaf, een groeiende arbeidsproduktiviteit en schaarste op de arbeidsmarkt van groot belang... Daarin zou de sleutel kunnen liggen voor de oplossing van het vraagstuk dat in Holland - ondanks een snel groeiende bevolking - koopkracht en levensstandaard vanaf 1535 zich verhoudingsgewijs gunstig ontwikkelden (182; see also 95)Ga naar voetnoot2. If I were writing The Dutch Rural Economy today, I could rely on Hollands Welvaren? to make exactly the argument that I made with the help of the unsatisfactory data discussed above. But, were I to do so, I would be no less vulnerable to criticism than I am now. In ten year's time a certain Dr. Zuidegraaf would dismiss as unreliable the study that now appears to offer me precisely what I want. What are the shortcomings of Noordegraaf s book? | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The standard of livingAny study aspiring to chart trend and level of the standard of living in Holland must present new evidence describing wages, for that is the subject about which the least is now known. Ideally, we should like to be presented data on several occupations, at several locations both urban and rural. It would be unrealistic to suppose that archival sources always allow such an ideal to be realized, but Noordegraaf shows little interest in the need for diversity. He confines his analysis to the wages paid to two occupations, masons (metselaars) en hod carriers (opperlieden), in two cities, Haarlem and Leiden. For the description of seventeenth century developments he adds data from Alkmaar (drawn from his exemplary study Daglonen in Alkmaar, 1500-1850), and wage quotations from several other cities are displayed in graphs, but these are not actually used in the analysisGa naar voetnoot3. Noordegraaf apparently felt no need to cast a wider net because of his confidence that Haarlem wage rates reflected faithfully the rates in other cities (172). But the limited data presented in Hollands Welvaren? shows that this confidence is misplaced. Haarlem and Leiden ‘metselaars’ wages varied greatly through most of the sixteenth century, as Noordegraaf himself acknowledges. Moreover, Haarlem's wage rates did not always correspond to those of other cities. Consider conditions in 1555, a year chosen only because Noordegraaf has data for several cities in or around this year. In the eight time series drawn from six cities displayed in Noordegraaf'ss graphs the day wages of metselaars varied from 6 to 12 stuivers. The highest rate, double the lowest ones and 50 percent higher than any others, was paid in Haarlem. Apparently, the information that emboldens Noordegraaf to regard Haarlem as representative of Holland's cities is drawn from some other, unnamed, source. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

[pagina 231]

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

To calculate real wages nominal wages must be deflated by an index of prices paid by the type of wage earner in question. Ideally, the index should be composed of prices for all the major types of expenditure (food, clothing, fuel, housing, taxes) and the prices should be weighted by their share of total expenditures. Published price time series do not permit the construction of the ideal ‘consumer price index’ for sixteenth century Holland, but the many commodity prices published by Posthumus and others make it possible to approximate such an index. Indeed, long ago Posthumus constructed one for use in his Leidsche lakenindustrieGa naar voetnoot4. Here, again, Noordegraaf shows little interest in questions of representativeness. He quickly satisfies himself that the ‘customary’ use of grain prices as the single measure of purchasing power will suffice. Is this because other prices behave much as grain prices? There is abundant evidence to the contrary. Is it because expenditures on grain overwhelmed other expenditures in the typical worker's budget? There is reason to believe that a diversified diet makes this assumption less valid in Holland than in other regions of Europe. In any event, Noordegraaf does not let these matters detain him. His study is based entirely on Utrecht and Leiden time series for wheat and ryeGa naar voetnoot5. Thus far we see Noordegraaf declining every opportunity to improve upon the conventional, limited approach to the historical study of the real wage. With the data just described he is in a position to calculate the liters of rye or wheat that could be obtained by a day of labor as a bricklayer or helper in Haarlem or Leiden. This has the virtue of being a straightforward calculation, and one that can readily be compared to similar work done long ago by other European scholarsGa naar voetnoot6. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

[pagina 232]

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

But at this point Noordegraaf raises his sights; he is not content with such a ‘technical’ measure of purchasing power. To measure something closer to the standard of living he proposes to calculate average annual earnings. This requires knowledge of seasonal differences in the daily wage (winter versus summer wages) and the number of days worked per year. Noordegraaf confronts an important and neglected event in Holland's economic history, the abolition of saints' day by the Synod of Dordrecht in 1574. In theory the maximum number of working days suddenly rose by approximately 50 to 312 days per year. In practice, the change was less sudden, since the observance of many religious holidays had been in decline for some time; nor was observance of the 1574 decree universal and instantaneous. Nevertheless, in the course of several decades the labor market experienced an important institutional change, one that increased the maximum work year by about 20 percent. Another factor affecting annual earnings is unemployment (whether caused by economic problems, severe weather, civil disturbance, epidemic, etc.). Noordegraaf makes an important contribution in constructing a rough chronology of periods of relatively strong and weak demand for labor (more about this below), but this does not make it possible to actually specify the average annual number of workdays lost for these reasons. Consequently, he lets himself be guided by a handful of historical examples to set the average annual number of days worked at 245 up to 1540, 260 from then until 1575, and 275 thereafter. These are ‘stylized facts’ intended to serve as approximations of the long term trend. Noordegraaf's use of these ‘stylized facts’ is puzzling. He bases his rejection of more broadly based approaches to the measurement of wages and prices on the argument that these do violence to historical ‘reality’. He wishes to make tangible statements about specific types of workers: for example, liters of rye purchasable by masons employed by the stadfabriek of Haarlem, rather than an index of purchasing power of construction labor in Holland. Yet his estimates of average annual days worked corresponds to no reality, and imposes on the final calculation of purchasing power an uncheckable bias. It would have been far better to make the calculations on a daily basis, and/or on a maximum annual earnings basis. Then further adjustments for unemployment could be made explicitly. By now it must be clear why Noordegraaf's calculations of the standard of living in Holland are inadequate to their task: they are too narrowly based in terms of occupations, locations, and prices, and whatever ‘realism’ they possess is placed in jeopardy by the assumptions made about the number of days worked. If we place these objections aside for a moment, what patterns do the calculations of purchasing power reveal? Noordegraaf presents his findings in a series of graphs of annual and smoothed data. All of the time series have substantial lacunae, and Noordegraaf rejects as too hazardous the combining and splicing of the separate time series to reveal long-term trends. We are left with Noordegraaf's descriptive statements based on impressions that are never expressed in quantitative terms. He seems to have examined each time series separately, but he seems never to have compared them. I say this because comparisons reveal anomalous patterns that cry out for explanation, but the book makes no mention of them. The rye purchasing power of the same occupation in the same city can vary by over 50 percent in the same year depending on which employer and which price series is usedGa naar eindnoot7. A particularly knotty problem is presented by the inconsistencies between the earnings of metselaars and | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

[pagina 233]

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

opperlieden working for the St. Catherijnengasthuis and the stadfabriek of Leiden. The gasthuis time series ends in 1569 while the stadfabriek series begins in 1575. Using the same Utrecht market prices, rye purchasing power rose from 6.4 to 12.1 liters for opperlieden and from 11.0 to 15.2 liters for metselaars. In the same interval employees of the Haarlem stadfabriek (also using Utrecht market prices) saw their rye purchasing power fall: opperlieden from 10.6 liters in 1569 to 8.8 liters in 1575; metselaars from 20.7 to 13.6 litersGa naar voetnoot8. How can we accept these time series as representative for Holland so long as these anomalies are not discussed? Noordegraaf devotes little attention to these issues because his chief interest (his probleemstelling notwithstanding) is short-term fluctuations in the standard of living. Much of the book is devoted to the identification of periods of high prices, low purchasing power, and general economic difficulty. The most impressive contribution of the book is Noordegraaf's corroboration of quantitative evidence about crisis periods with literary evidence. One could wish for greater precision in the dating of crises and in the measurement of their severity, but Noordegraaf's contribution remains valuable. It is interesting to note that his identification of periods of high and low purchasing power (113-115) and of high and low demand for labor (77-90) largely coincide. This means that high unemployment was compounded by low real wages while high levels of employment were reinforced by high real wages. This conjuncture is well known for the relatively brief crise de subsistence; its implications for the longer periods of expansion and malaise delineated by Noordegraaf deserve further study. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The labor marketBecause he emphasizes short-term variations in his analysis of real wage data, Noordegraaf's conclusion that real wages in Holland held up and even rose in the course of the ‘long sixteenth century’ is not given great prominence. This reviewer's position has been that Noordegraaf's conclusion is probably correct, but that he has not succeeded in putting that position on a firm quantitative footing. We now turn to Noordegraaf's explanations of the labor market behavior that yielded the pattern of wages just discussed. Here I shall argue that his analysis is confusing and, in places, patently wrong. Moreover, where his observations are correct and valuable, they are not given the emphasis they deserve. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

[pagina 234]

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

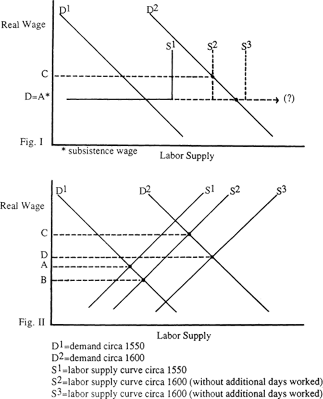

Noordegraaf's discussion of factors determining the standard of living (177-184) is a desultory review of a wide variety of variables, with little or no effort to rank their importance, chart lines of causation, or distinguish short-run from long-run factors. Since the author himself is apologetic about this weak effort (184) I will pass over it to consider his views about long-run changes in wages. (He claims to be speaking about nominal wages, but as we shall see, he is confused on this point. Sometimes he is discussing real, sometimes nominal wages.) Noordegraaf introduces three explanations for the rise in nominal wages that begins around 1540 and proceeds into the 1630s: 1. price inflation, raising the cost of subsistence; 2. the workings of supply and demand for labor; 3. technical and organizational changes that yield increased labor productivity (90-95). The argument that rising prices ‘cause’ rising wages depends on the existence of subsistence level wages. If wages are above the subsistence level some institutional or behavioral explanation must be invoked, which reduces the rise of prices to a background factor. There are two good reasons to reject rising prices as the major cause of rising nominal wages in Holland. First, grain prices rose substantially from the 1460's without occasioning an adjustment of wages until 1540. And when wage rates did move upward, rye prices stood at a level that had been common since 1520. It is hard to see how prices can explain the increase in wages around 1540 when they had risen earlier and exhibited relative stability in the two decades immediately preceding 1540. The second reason to reject this view is more general: the real wage did not stand at subsistence, if that is taken to mean an irreducible minimum standard of living. Noordegraaf's review of sixteenth century wage trends in other European countries confirms that wage laborers suffered major reductions in purchasing power almost everywhere (157-166). Since neither the nominal levels of these wages nor their rye purchasing power was originally greater than in Holland it cannot be argued that wages in Holland were irreducibly low. Holland's workers suffered many periods of scarcity and misery, but the example of workers in other countries teaches us that it could have been worseGa naar voetnoot9. Noordegraaf implicitly recognizes the insufficiency of price inflation as a cause of nominal wage increases when he introduces his ‘vision’ of how supply and demand functioned in the labor markets of pre-industrial Holland. The demand for labor did not place upward pressure on the wage rate until the supply of labor was exhausted. Likewise, reduced demand did not cause wages to fall; it simply produced unemployment (90-91). In other words, all responses to changes in the demand for labor took the form of quantity adjustments and none took the form of price (wage) adjustments. Figure I displays the type of supply and demand situation that Noordegraaf apparently has in mind. The supply of labor is perfectly elastic at a given (presumably subsistence level) wage. When the labor supply (defined by the legal and customary constraints on employers and employees) is exhausted, wage rates rise as employers compete for each | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

[pagina 235]

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

[pagina 236]

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

others workers. This characterization of the supply curve of labor assumes that workers place no value on leisure and are prepared to work as much as physically possible at the going wage. When the supply is exhausted one of two things happen: wages are driven up or the rules governing the length of the work year are changed. This account conveniently forgets an alternative source of labor: immigration. If the supply of labor is perfectly elastic at the subsistence wage there must be reserves of unor underemployed labor in outlying regions that can be tapped. There is little reason to expect that the vertical section of the supply curve would ever be reached. Indeed, this view prevails among economic historians who have addressed the issue. Van Ravesteyn, in 1906, Charles Boxer, in 1965, and Van Dillen, in 1970, all held that the very attractiveness of the Republic's labor markets caused them to be chronically oversupplied, making improvements in the real wage impossibleGa naar voetnoot10. An alternative approach, embodying more conventional assumptions about labor market behavior is presented in Figure II. There the short-run supply curve is elastic: higher wages increase the amount of labor offered. Over time the growth of population causes the entire curve to shift toward the right. Between 1550 and 1600 Holland's population grew by roughly 67 percent (from, say, 300,000 to 500,000). If the demand for labor had not also increased the equilibrium real wage would have fallen (from A to B). Something like this happened in most of Europe in the course of the sixteenth century. In Holland the demand curve also shifted to the right, indeed, it shifted so far as to substantially increase the equilibrium wage (point C). In addition, the maximum length of the work year rose by 20 percent. This has the effect of shifting the supply curve yet further to the right (S³). Note that the combined effect of population growth and the reduction of feast days doubled the volume of labor available at a given wage in the course of the second half of the sixteenth century. This doubling seems to have been composed of three roughly equal parts: natural increase, immigration, and extention of the work year. The increase in demand sufficed to absorb this augmented supply at a real wage that was at least equal to its earlier level. Figure II placed it at point D. Figure II presents a labor market model that avoids reliance on the extreme assumptions that adhere to Noordegraaf's approach. Labor need not be assumed entirely indifferent to leisure, the abolition of saints' days need not be interpreted as an expression of economic necessity, and wages need not be assumed to rest at bare subsistence. In addition, figure II is unambiguously a representation of factors affecting changes in the real wage, while Noordegraaf's model is confusing on this score. He claims to be discussing nominal wages, but the horizontal ‘subsistence wage’ that dominates his account must be a real wage concept. This brings me to Noordegraaf's third explanation for the behavior of wages in sixteenth century Holland: increased labor productivity. This had been my explanation in 1974 for Holland's deviant behavior and, as I noted above, it is emphasized by Noordegraaf as well. This is an explanation of real wage growth, of course (contrary to Noorde- | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

[pagina 237]

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

graaf's repeated assertions to the contrary). It is not compatible with Noordegraaf's subsistence wage arguments, but is compatible with the model shown in figure II | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

ConclusionI have taken some pains to review the explanations offered in Hollands Welvaren? even though they are amateurish and contradictory. My objective is not (simply) to embarrass the author, but to call attention to the fact that no amount of data gathering (and this study unfortunately cannot be faulted for excessive data gathering) can overcome methodological and theoretical ignorance and/of casualness. The data do not ‘speak for themselves’. In these reactionary times the historical profession is being called upon to retreat from the new initiatives made possible by the incorporation of social scientific theory and quantitative methods in historical research. Our aim should be to make history the focal point of social theory rather than simply to convert history into an applied social science. But today the call is out for a return to intellectual isolationism. The claim is made that traditional philological research, source criticism, and casual empiricism should be restored to their rightful position at the core of the disciplineGa naar voetnoot11. The argument is artfully presented as nothing more than a desire for balance. Who, after all, can fail to acknowledge the importance of correct readings of historical documents? No one should be misled about what is at stake. The weakness of the book under discussion here is a case in point. We do not know how representative Haarlem is of Holland; we do not know how representative rye prices are of the cost of living; we are told nothing specific about trends in the real (rye) wage; we are left with crude impressions of the short term variations in real wages; the account of labor market behavior is transparently inconsistent and naive. How can our understanding of the issues addressed in Hollands Welvaren? be advanced by a work so informal in its method and so idiosyncratic in its design? How can history ever lose its reputation as a ‘gezelschapsspel voor fijne luiden’Ga naar voetnoot12 when its practitioners devote themselves to the savouring of nuances (184) to the neglect of acquiring a basic understanding of the phenomenon at issue? | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

[pagina 238]

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

AppendixThis argument is made with vigor by Leo Noordegraaf in ‘Het platteland van Holland in de zestiende eeuw’, Economisch- en sociaal-historisch jaarboek, XLVIII (1985) 8-18. In that article I am held up (‘by coincidence’ says the author) as an example of an historian so blinded by theories and models that I fall into grievous error, misinterpreting key developments of rural economic history. He accuses me of three specific mistakes: misreading the descriptions of occupational structure provided in the Enqueste of 1494 and the Informacie of 1514, misinterpreting a document containing the 1557 request of the village of Nieuwe Niedorp for privileged markets, and distorting the chronology of Alkmaar's market development. These errors, he argues, suffice to undermine my argument that Holland experienced rapid rural specialization in the sixteenth century. Noordegraaf's claim that I misread the Informacie and exaggerate the lack of occupational specialization is without merit; it rests on his overly literal reading of the texts and his misreading of my book, particularly pages 72-73. No amount of close reading of the Informacie will suffice to determine whether the village that supported itself with ‘a little’ farming, fishing, fowling, peat digging, seafaring, etc., did so with every villager a specialist in one activity or with every villager a ‘jack of all trades’. Sometimes the words provide clues (as Noordegraaf concedes); more often the words must be placed in a context of other information, and of a model of the household economy. None of Noordegraaf's objections are more than speculations. Noordegraaf's objection to my abbreviated presentation of the Nieuwe Niedorpers' request for market privileges is valid. He is correct to emphasize that the village possessed a de facto market in 1557 and sought to have it recognized as a ‘vrije markt’. It did this because many other places had recently established markets, and all these were now threatened with suppression by a plakkaat forbidding forestalling (voorverkoop). Noordegraaf corrects my explanation of the petition, but he only strengthens my argument that local markets were becoming more common. Noordegraaf's view that the suppression of rural markets was a periodic occurence, and thus signified little, is hard to credit when one takes cognizance of the historical context of strenuous measures to limit rural commerce: the Order op de buitennering of 1531, a failed effort to suppress rural commerce in Friesland in the same year, the renewed establishment of rural markets after the Revolt, and the Friesian measure of 1602, forbidding non-urban scales except where they had existed for at least 40 years. Noordegraaf is right when he emphasizes the lack of certainty in the interpretation of sources pertaining to market development but this works against his argument more than against mine. Philology provides no sufficient answers to the questions posed in my study. Noordegraaf's claim that I have garbled the chronology of Alkmaar's market development is also correct. Indeed, it is embarrassing to admit that the reason he suggests for this (‘door het omvallen van een kaartenbak’) is close to the truth. The event that I ascribe to 1408 is properly placed in 1545. The error came from conflicting information provided in two secondary sources (C.W. Bruinvis, Geschiedenis van de kaasmarkt..., 4-5; P.N. Boekel, De zuivelexport van Nederland, 21-22) and G. Boomkamp's chronicle, 10, 110. The year 1408 marks the earliest mention of the Alkmaar weighhouse, and the | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

[pagina 239]

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

story of its contracting hinterland and expanding volume concerns the sixteenth and early seventeenth century. Chronology is, to be sure, a holy cow (as Noordegraaf expresses it), but the corrected chronology does no violence to my interpretation of the economic processes - it improves it. The point to be made here is that an old fashioned mistake (first made in 1929) and not an effort to force facts into rigid models is the source of the trouble. The argument of Dutch Rural Economy is certainly in need of revision. I am now of the opinion that the study overemphasized the early sixteenth century as the beginning of economic development. But I made that error originally because of ‘traditional’ historical periodization and my historian's respect for documents (the Enqueste, and the Informacie), not because of the dictates of models. Moreover, my improved understanding has come not from ‘traditional source criticism’ but from the clever quantitative work of D.E.H. de Boer, Graaf en grafiek (Leiden, 1978). Noordegraaf felt that three examples illustrating the evils of theory-infused history would suffice to win his case: ‘drie maal is scheepsrecht’ (15). For various reasons (not all of which do me credit!), none of these examples supports the argument he seeks to make. I therefore feel justified to counter with the American expression: ‘three strikes and you're out’. |

|