Folium Librorum Vitae Deditum. Jaargang 3

(1953)– [tijdschrift] Folium–

[pagina 1]

| |

[Nummer 1-2] | |

Oscar Wilde's Ballad of Reading Gaol

| |

[pagina 2]

| |

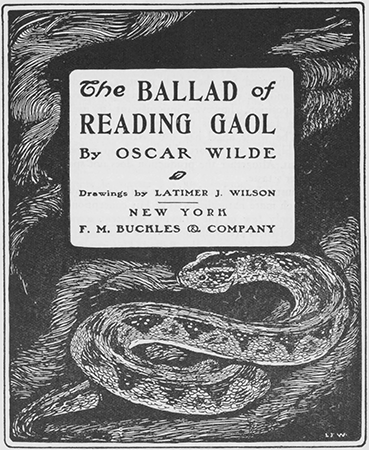

promised at once to do a frontispiece for it - in a manner which immediately convinced me that he will never do it’Ga naar eindnoot83). On 2 October 1897, Wilde writes to Smithers from Naples that he hopes the second edition would be illustratedGa naar eindnoot84). But only nine weeks later, on 8 December, he reacts unfavourably to the proposal of Elizabeth Marbury, the American literary agent, for an illustrated edition: ‘Her suggestion of illustrating is of course out of question. Pray tell her from me that I feel it would entirely spoil any beauty the poem has, and not add anything to its psychological revelations. The horror of prison life is the contrast between the grotesqueness of one's aspect and the tragedy of one's soul. Illustration would emphasize the former, and conceal the latter. Of course I refer to realistic illustration’Ga naar eindnoot85). Fairly soon, however, Wilde must have changed his mind once more. For Davray, in describing his collaboration with the author on the French translation, states expressly that Wilde spoke more than once about an illustrated edition of the Ballad and liked to picture to himself the drawings, type, size, and binding. The poet and the translator even tried jointly to interest a publisher in a bibliophile edition, and, says Davray, sketches for the drawings were submitted. But the plan came to nothingGa naar eindnoot86). It took nine years until the first illustrated edition appeared. The firm of Buckles & Co. in New York, encouraged by the enormous popularity of the poem and the lack of any copyright protection in the United States, published in 1907 an edition with pen drawings by Latimer J. Wilson. It is a large octavo volume without any typographical merits. On every page the text is framed in a double border of thorns and accompanied by a marginal drawing (borders and drawings printed in brown). This edition has become so scarce that, apart from a copy in my own collection, I could trace only three copies, all of them in American Public Libraries: one in the Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. (where it is kept in the Rare Book Department), one in the Cincinnati University Library, and one in the Clark Collection. The title is framed by a design representing a serpent and clouds. Each of the six parts of the poem is preceded by a half-title with a vignette and each begins with a head border and ends with a tail-border, which is twice combined with the marginal drawing. The illustrations of the book thus comprise: a border round the title, six half-title vignettes, three headborders, 27 marginal borders. (of which two are repeated un- | |

[pagina 3]

| |

Title page of the first illustrated edition, 1907. Original size.

| |

[pagina 4]

| |

changed and two others reversed), two combined marginal and tail-pieces, and lastly a cover-design in three colours (black, white and gold, on grey cloth) representing a mourning angel with three doves above and four roses underneathGa naar eindnoot87). In 1923 the book was reprinted by Peter P. Mulligan Inc., New York. In this new edition, the same blocks appear to have been used, but the title border is missing. The cover-design, which is repeated on the dust jacket, is printed from the old die, but only from that originally used for the black printing, the doves at the upper edge and the rose at the lower being omitted. Thus the artist's composition, however insignificant in itself, has been destroyed, a fact which is not apparent to the unsuspecting spectator. The white angel has also been left out, and all that remains are his hood and a part of his wings: an entirely meaningless ornament. Altogether the production does not speak well for the publisher's taste. Wilson's illustrations, though clearly influenced by Beardsley, are in a much more naturalistic style. His conception of the task was right: only few of the drawing represent scenes from the poem; most of them are symbolic, and the ideas expressed in them correspond with those of the Ballad. Unfortunately Wilson's abilities lagged far behind his intentions and the artistic quality of the drawings is only slight; their sole importance lies in their chronological priority. The next illustration to the Ballad, a heliogravure after a drawing, originated at the same time as Wilson's designs, but did not appear until two years later, in the Sunflower Edition of the Collected Works, published in 1909 by the Lamb Publishing Company ([vol. I], Poems, p. 265), The caption ‘... Each evil sprite that walks by night’ connects it with Part III, stanza 19. It represents a man half rising from his resting place and seeing a vision which is indicated by two grimacing devils in the top lefthand corner. The signature reads: ‘Albert Hencke, Copyright 1907 by A.R. Keller & Co. Inc.’ The artistic quality is again very mediocre. In the same year, 1907, the H.M. Caldwell Co. of New York and Boston published the Ballad as No. 57 of their ‘Remarque Series’. The frontispiece, by an unnamed artist, is in the naturalistic manner of the eighteen-eighties and shows the gateway of a castle in the style of Windsor, probably intended to represent the prison. Bottom left there is a minute head of Wilde in the form of a | |

[pagina 5]

| |

remarque (from which the series probably derived its name). The illustration has no artistic merit. It was repeated as frontispiece to the undated edition of the Dodge Publication Co., New York, which came out probably in 1915. In Europe it is Germany that can claim the honour of the first illustrated edition. Holitscher's translation, published by the Axel Juncker Verlag of Berlin-Charlottenburg in 1916 (imprint without date of publication) is accompanied by five full-page line blocks after drawings by Otto Schmalhausen. Four of them are purely symbolical, and the artist has not followed the text too closely: the fleeing murderer in the woods, a prisoner in his cell, staring into the light, a figure moving in an imaginary prison yard with a gallows against the sky, the murderer collapsed under the starry sky, and lastly a cathedral with white figures and a dead man in the foreground. Schmalhausen's interpretation of his task may be considered quite legitimate but his drawings have little artistic merit and are in no way worthy of the poem and its importance. The first valuable illustration to the Ballad appeared in 1918, when the Hyperionverlag in Berlin published Felix Grafe's translation with a frontispiece by Alfred Kubin (950 numbered copies, the first 50 on handmade paper). It represents the chained murderer, a figure of exuberant vigour with the sinister expression of a maniac. In choosing for his theme the immediate, and not intrinsically important, motif of the ballad instead of grappling with its real substance, Kubin has evaded the real problem. But if he had to limit himself to one drawing, he was certainly justified in taking this course. And as he had to draw a frontispiece to serve as an introduction, I feel that in picturing the man whose act is the starting-point of the poem, Kubin did better than all the other artists whose task was, like his, limited to a single illustration. For they, with few exceptions, chose for their subject a scene from the poem. The other illustrated edition of the same year has also high artistic merits. It is the French translation by Davray with two-colour woodcuts by Daragnès, printed by the master-printer Léon Pichon in 395 copies: Nos. 1-30 on Japan paper, with a double set of the woodcuts and one original drawing by the artist; the other copies with a single set, Nos. 31-80 on China paper, Nos. 81-180 on Imperial Japan, and Nos. 181-395 on hand-made Van Gelder paperGa naar eindnoot88). The woodcuts comprise a small title | |

[pagina 6]

| |

vignette representing a knotted noose; a headpiece and a tailpiece to each part (except the third, which has only a headpiece); one woodcut inserted in the first part, eight in the third part, two in the fouith part and three in the fifth part.

Daragnès. Woodcut in two colours. From the French translation by Davray, published by Pichon, 1918. Original size.

Thus the total number of woodcuts (without the title vignette) is twenty-five. All of them are printed in black over a flat pale umber tone, which gives the prints the intended sombre and tragical character. None of the illustrations is full-page; they are all interspersed in | |

[pagina 7]

| |

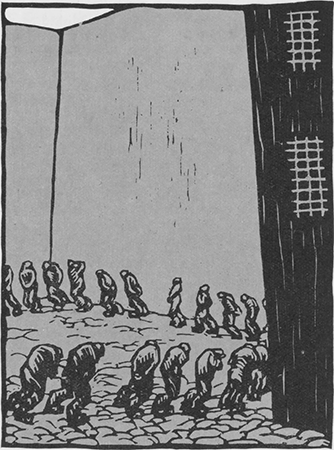

the text, and the prose of the translation results in a well-balanced type area, alternately stressed and relieved by the woodcuts. Apart from the use of a square typographical ornament, which looks rather dated, the book is altogether beautifully printed in 12 point Cochin Roman. The artist was not intent upon following the text closely; instead he created a kind of melancholy accompaniment blending into complete unity with the words. Only in a few cases does he refer directly to situations depicted in the Ballad, e.g. in the two illustrations of the walk in the prison yard, the second time by the open grave. Most of the woodcuts represent the prisoner in his cell and concentrate upon expressing the mood and conveying the atmosphere. The few woodcuts on different themes show the same tendency to paraphrase, e.g. a bird's-eye view of the prison buildings or an empty corner of the courtyard with the open grave. The manner in which the artist tackles the vision of phantoms in Part III is characteristic: whereas the second-rate illustrators vie with each other in mustering devils' grimaces and ghosts, Daragnès contents himself with purely ornamental silhouettes, which in their very disembodiment have a much more uncanny effect than any number of banal horned monsters. The volume opens with Davray's foreword (referred to above), in which the translator describes his collaboration with Wilde and their common efforts to find a publisher for an illustrated edition. He goes so far as to assert that this was the first edition to be illustrated, a claim which we know to be unjustified. But it must be admitted that the Ballad appears here for the first time with illustrations of artistic merit and in a really fine bibliophile production; the edition of the Hyperionverlag has only a frontispiece and thus cannot be classified as illustrated in the proper sense of the word. In the following year appeared the Czech edition with woodcuts by František Kobliha. In addition to one illustration proper, a frontispiece of a seated male figure in a sombre fantastic landscape, the artist has cut three vignettes, one for the title, one for the text, and one for the end, all of them purely ornamental; the text vignette is repeated at the end of each sectionGa naar eindnoot89). In the frontispiece it was clearly the artist's intention to capture the mood of the poem, but his illustration is too general to achieve the purpose: it would be equally well suited for dozens of other | |

[pagina 8]

| |

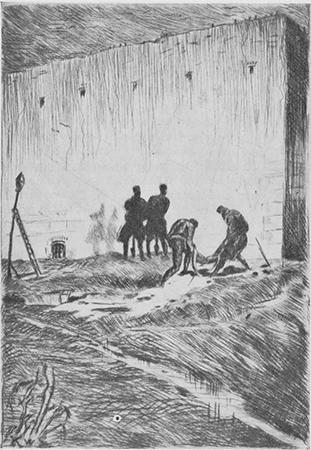

works of tragic poetry. A comparison of Kobliha's frontispiece with Kubin's shows well how much better the latter has succeeded in creating a true illustrative introduction to the events of the Ballad. The translation by Felix Grafe, to which Kubin had contributed a frontispiece in 1918, was republished by the Hyperionverlag in 1920 (undated like the first edition) with a cover design by an excellent graphic artist, Emil Preetorius of Munich. This edition is a volume of the ‘Jedermanns-Bücherei’, a series in miniature size (91 × 64 mm) devoted to masterpieces of world literature, illustrated by good artists and neatly printed. The Ballad is set in a rarely used typeface, the Ehmcke Rustika; the illustration represents three prisoners during exercise, in a silhouette manner which Preetorius has used on several other occasions with impressive resultsGa naar eindnoot90). The Hungarian edition de-luxe published by the Dante Press in Budapest in 1921 is not very successful. It is a royal quarto volume (315 × 228 mm), printed on the recto pages only and containing eight signed etchings by Gyula Komjáti Vanyerka. They are ‘pictorial supplements’ of the most oldfashioned kind, as is already evident from their dimensions: size of each etching 130 × 86 mm, size of the plates about 145/150 × 110/115 mm. This size is not related to the dimensions of the book nor to those of the type area, and the intrusive effect of the etchings in further increased by the one-sided printing, through which each etching faces a blank page. The prints as such are well etched, but they are completely academie and devoid of imagination. The meaning of the first print has so far eluded me: by the side of a naked girl of blank, doll-like beauty stands a man in evening dress, whose repulsive, leering face is that of a sensual rake; in the background there is an indication of some heads peeping from behind a curtain, one of them also leering. The illustration would be convincing as that of a Budapest brothel scene but not as bearing on the Ballad. The other etchings fit in better with the spirit of the poem: the murderer by the bed of his victim, the prisoner staring towards the light with a yearning look, the round in the prison yard with two warders, the prisoner in his cell, then the gallows (with a hangman straight from the opera), the visions (with ghosts drawn in a naturalistic way), and the burial of the executed manGa naar eindnoot91). The year 1923 yielded the richest harvest of illustrated editions | |

[pagina 9]

| |

of the Ballad - no fewer than four; one of them, the American reprint of the illustrations by Wilson, has already been discussed. The other three appeared in Germany.

Gyula Komjáti Vanyerka. Etching. From the Hungarian translation by Arpád Tóth, 1921. Original size.

This was no mere coincidence: the German inflation, then at its height, led to a general flight from money into all manner of goods, also into books, with a consequent boom in editions de-luxe. These were by no means | |

[pagina 10]

| |

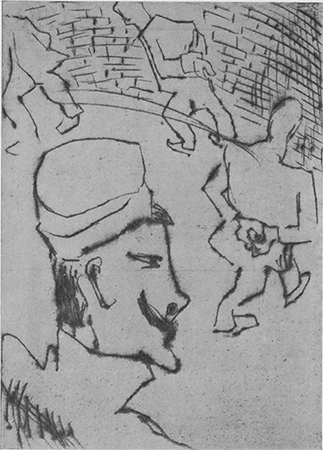

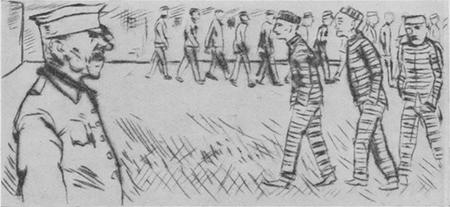

all in good taste, but the Ballad came off well, for all three editions of it were illustrated by serious artists who deserve closer study. The Axel Juncker Verlag, which seven years earlier had brought out the first illustrated edition to appear in Europe, now commissioned Otto Pankok (not to be confused with Bernhard Pankok, the purely decorative artist) to illustrate the Ballad. His seven etchings - five full-page ones, a vignette at the beginning (the publisher's emblem) and one at the end (a skull) - accompany Holitscher's translation in a de-luxe editionGa naar eindnoot92). This imposing quarto volume, beautifully set in 16 point Walbaum RomanGa naar eindnoot93), is the only edition of the Ballad to contain expressionistic illustrations. Anyone averse to expressionism will not think the etchings beautiful, but he too will have to admit that they are highly expressive and form a moving accompaniment to the text. The subjects are simple: the murderer, the prisoner looking up towards the light, the round in the prison yard (with a back view of three prisoners and the main accent on the warder's head in the foreground), the prisoner in his cell, and finally the hanged man. The etchings have been designed with the greatest economy - the cell for instance is rendered convincingly with a few lines suggesting a corner - and by this means the artist has achieved a concentrated tragical effect. Finally mention should be made of the cover vignette in black and red, a radiant sun behind bars, which also evokes an atmosphere of excitement. The edition illustrated by Rudolf Schlichter, and published by O.C. Recht in MunichGa naar eindnoot94), contains not a German translation but the original English text. Of all editions of the Ballad it is the most profusely illustrated: it has no fewer than 60 etchings. The whole of the text is printed in small capitals; on most pages there are two stanzas, on some only one. Each page is decorated with an etched headpiece 88 mm wide (equal to the width of the imaginary type area) and 40 mm high - an arrangement that made possible a complete uniformity in the appearance of the pages. This uniformity is disturbed only where the printer who overprinted the etchings failed to place one or the other in correct position. Rudolf Schlichter belongs to that school of German artists which prepared the transition from Expressionism to the Neue Sachlichkeit, the school to which George Grosz also belonged. Like the latter's, Schlichter's art has a pronounced social bias and hence | |

[pagina 11]

| |

Otto Pankok. Etching. From the German translation by Arthur Holitscher, 1923. Original size 187 by 135 millimeters.

| |

[pagina 12]

| |

Rudolf Schlichter. Etchings. From the edition published by O.C. Recht, Munich [1923]. Original size.

| |

[pagina 13]

| |

his prints are severe in their lines and militant in conception. The large number of illustrations has enabled the artist to give artistic expression to all the situations in the Ballad, from the murder to the purification of the malefactor. Most typical are such prints as that on page 21: to illustrate the lines; ‘It is sweet to dance to violins when love and life are fair’, the artist has produced a biting satire on modern amusement business, with girls of easy morals and coarse ‘gentlemen’ hunting after cheap pleasures. Another example is the illustration to the stanza beginning: ‘Around, around, they waltzed and wound’ (p. 37). There are no dancing spectres, but in the centre of the print stands Death in evening dress and top hat, behind him the naked body of a headless woman, before him a female figure like the écorchés illustrated in anatomy manuals for the study of tendons and muscles (i.e. only the raw flesh stripped of skin and fat), and in the background a few distorted, leering faces. An illustration such as this seems to me particularly instructive, showing as it does that Wilde has made so great an impression upon men of a sub sequent generation that he succeeds in touching their own proper problems. In Schlichter's mind, Wilde's ghosts are not just phantoms and spectres, but become immediately associated with the ghosts of his own time, the hectic and unhealthy period of the German inflationGa naar eindnoot95). The curious thing about this edition is that the publishers apparently reprinted the English text without the permission of Wilde's heirsGa naar eindnoot96). For even though under German copyright law anyone was free to publish a translation - since no authorized translation had been published within ten years of the first English edition - the unlicensed reprinting of the original was undoubtedly illegal. In assigning a third illustrated German edition to the year 1923, we are only partially correct. The edition in question is that containing the woodcuts by the well-known Flemish painter, woodcutter and illustrator Frans Masereel. The only indication of date in the colophon reads: ‘The woodcuts by Frans Masereel date from the spring of 1923’, but nothing is said about the publication date. According to the ‘Deutsche Nationalbibliographie’ the book was not available until 1924. Masereel tried to solve his problem by placing the murderer's person in the centre of his work. The volume contains seven full-page woodcuts and the criminal is depicted in all of them. | |

[pagina 14]

| |

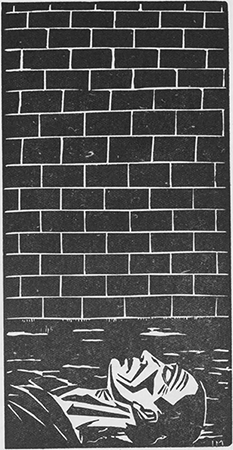

Frans Masereel. Woodcut. From the edition published by the Drei Masken Verlag, Munich, 1923. Original size.

| |

[pagina 15]

| |

In the first, on the frontispiece, he is shown standing upright, the hands in fetters, but instead of the head a board with the inscription C.3.3 (Wilde's number as prisoner, which appears also on the title-page instead of his name); in the last, at the beginning of the sixth part, his corpse in the prison yard. In the other five full-page woodcuts, which precede each of the first five parts, he is seen in attitudes related to the text of the poem: staring upwards, lost in thought, despairing, at prayer, and finally peeping through the bars of the door into the corridor. In this way the full-page woodcuts serve as pictorial accompaniment to the spiritual progress of the poem. The factual side of the story is illustrated in the halfpage woodcuts at the head of each part: the arrest at the scene of the murder, the round in the prison yard, the murderer between two gaolers, the prisoner in his cell, the hanged man on the gallows, the filling of the newly-dug grave. In addition to the woodcuts described, 23 small vignettes interspersed in the text enrich the book both by their contrast to the type and by their illustrative accentuation of the words. Some of these vignettes are symbolic, such as the murderer's hands dripping with blood, or Death peeping over the wall, others are illustrative, such as a hand with a dagger, the prison yard, the nocturnal vision, and others. The concluding illustration, a slightly larger vignette, shows the dead man under a rain of tears, and thus alludes to the basic sentiment of the poem: compassion. All in all Masereel has created 37 woodcuts for the Ballad. The typographical design of the book is exquisite. The text is set in the Bauer Foundry's black-letter type, whose heavy face blends into complete unity with the woodcuts, which are worked entirely out of the black. There are five stanzas to a page, equal in depth to the full-page plates. The half-page headpieces correspond in depth to two stanzas, the small interspersed vignettes to one. In this way the severe rhythm of the type area is preserved throughout and the eye is never disturbed by an unharmonious page. The edition was published originally by the Drei-Masken-Verlag of Munich, as the eleventh of their ‘Obeliskdrucke’, a bibliophile series issued by this otherwise purely literary publishing house. 340 numbered copies were printed, the first 70 of them on handmade paper; of this special set, Masereel has signed all full-page woodcuts, a fact not mentioned in the colophon. In the autumn of 1925, a year after the edition had been pub- | |

[pagina 16]

| |

lished, a further 500 copies, including 50 on hand-made paper, were sold to Methuen & Co., London, in flat sheets. They were overprinted with Methuen's imprint and bound in London, - the unusual case of a de-luxe edition with original illustrations being distributed as such in two editions. Of all illustrated editions of the Ballad, the Masereel edition seems to me to have the highest artistic importance. This is necessarily a subjective estimation, but I must confess that, both in conception and in execution, Masereel's woodcuts have made the deepest impression on me. Surely there can be few who will remain unmoved by their suggestive power. The Yiddish translation by Karlin, published in New York in 1925, has a cover-design by Z. Maod, an illustrator not quite unknown in the United StatesGa naar eindnoot97); the design is repeated on the dustwrapper. Slightly expressionistic in manner, it represents the prisoner in his cell, bowed down by the burden of his deed. The Hebraic lettering worked into the drawing is anything but successful and recalls the worst lapses of the German Jugendstil. Owing to the poor technical execution of the printing, I have been unable to determine whether the design is a woodcut or a pendrawing done in woodcut manner; the latter seems to me more likely. The illustrations of the highest technical perfection and ingenuity are those in the French edition published by Javal und Bourdeaux, Paris, 1937. This is a re-issue of the old translation by Davray, but with a considerably longer preface than that in the Daragnès edition of 1918. The coloured illustrations were designed by G. Cornélius and each etched on three different plates by Thévenin. The desired polychrome effect is achieved by printing the three colours side by side and over each other. The results that can be attained by means of this difficult and rarely used technique of printing from original plates are often amazing, and one cannot enough admire the masterly skill of the printer. Cornélius has created nine full-page and six half-page drawings for the BalladGa naar eindnoot98), besides some vignettes in line-etching. But the illustrations, and indeed the book as a whole, arouse very mixed feelings. Certain artistic qualities of the etchings cannot be denied; especially the Wilde portrait at the beginning and the purification of the murderer at the end of the book are decidedly impressive. Yet we remain unsatisfied. The etchings are overcoloured, many figures are too large and burst the format of the book; the whole | |

[pagina 17]

| |

is too pretentious and one is left wondering whether the illustrations should not have been relegated to a less obtrusive role. The same applies to the typographical design. The book is handprinted in two colours; there are 225 numbered copies on Imperial Japan. The printing is of high craftsmanship, but the typeface in which the poem is set, the broad half-bold Egyptienne, is not pleasing to the eye, the coloured oblongs on which the initials of each stanza as well as the page numbers are placed and which are repeated, for good measure, to the right and left of the running headlines, are too much of a good thing. The value set on this book by French bibliophiles, a value indicated by its relatively high price, is due, I believe, to its technical rather than to any typographical or artistic perfections. Here it is not possible to quote corresponding passages of the Ballad, because the illustrations are merely intended as background music and do not refer to any particular lines. After the Sunflower Edition of 1909, no illustrated edition had appeared in the United States for eighteen years, unless we count the cover-design by Maod. In 1927, Boni and Liveright published an imposing volume ‘The Poems of Oscar Wilde’, illustrated by Jean de Bosschère, in 2000 numbered copies. The Ballad, which runs from p. 239 to p. 271, has seven illustrations: a title vignette (a mask), three colour plates and three in black and white. Under each illustration appears the line by which it was inspired. The colour plates represent the murder (‘and murdered in her bed’ I, 1), the last night of the sentenced man (‘he lay as one who lies and dreams’. III, 14), and the horror of the fellow-prisoners (‘pale Anguish keeps the heavy gate’, V, 5). The black-and-white plates represent a prisoner in his cell (‘in the cave of black Despair’, II, 3), the hard labour (‘and sweated on the mill’, III, 9) and the phantom of the mad drummer (‘like a madman on a drum’, III, 34). The feeling of horror is well brought out in the black-and-white prints, although the literal interpretation of the metaphor that links the drummer with the poet's own heart is not convincing. The coloured illustrations, however, seem to me quite unsuccessful. It is true that they are most expertly printed in many colours, including even gold, but being elegant, fashionable, and superficial, they are diametrically opposed to the spirit of the poem. No doubt Wilde did occasionally display these qualities, but certainly not in the Ballad. The incongruity is the more curious as the whole volume of 336 pages has no more than | |

[pagina 18]

| |

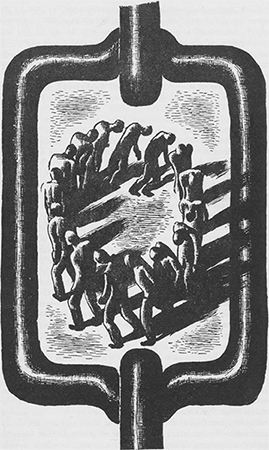

eight coloured and eight black-and-white plates and the artist, therefore, had a wide choice of poems to which his coloured prints would have been better suited.  John Vassos. Pencil drawing. From the edition published by E.P. Dutton & Co., New York, 1928. Original size 162 by 128 millimeters.

Already in the following year two new illustrated editions appeared in New York, one published by Dutton & Cie., with compositions by John Vassos, the other by Macy-Masius (The Van- | |

[pagina 19]

| |

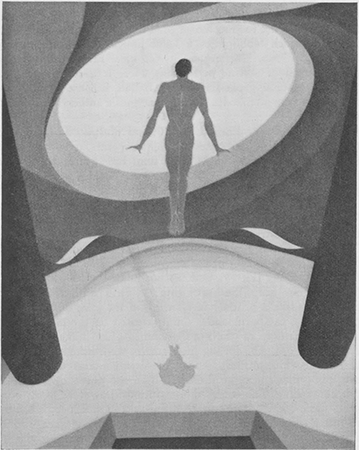

guard Press), with mezzotint drawings by Lynd Ward. John Vassos, a Greek emigrant to the United States, had made his name in the previous year with an illustrated edition of Wilde's SalomeGa naar eindnoot99). If his plates to Salome are full of pathos, this fits in well enough with the text. Not only is the play a tragedy, but its structure and language are of a certain theatrical showiness which an illustrator may legitimately imitate. But to embellish a work like the Ballad with opera settings seems hardly permissible, and this is just what Vassos has done. On opening the book, we find a frontispiece typical of his manner: an enormous, curving flight of steps rising up into the air amidst decorations, and on the topmost step a minute figure of a man with outstretched arms drawn in silhouette. Of the Ballad, with its tragedy and its vehemently accusing spirit, there is not the faintest trace. The other fifteen full-page illustrations continue in the same vein. The prison has become a grandiose temple with mighty vaults, the barred window of the cell is about twice as high as the prisoner standing before it (think of a prisoner's cell with a window 12 ft. high!), the pale spectre is a beautiful, thinly veiled female nude with one arm raised highGa naar eindnoot100). The publishers have spared no expense in the production of the book. The illustrations are admirably printed in the Knudsen process; there are only two stanzas on each page; not only the illustrations but also the pages facing them and bearing the captions have blank reverses. On the title page as well as on the cover there is a small ornamental vignette; the wrapper is not illustratedGa naar eindnoot101). The Macy-Masius edition is beautifully produced. It is in royal octavo format, set in Blado italics and printed on all-rag paper (according to the colophon, in 2000 copies). Every page has a border with figures, running down at the outside and of the same depth as the type area; there are six such border designs, each being repeated throughout one part of the poem. The title-page has two marginal borders with the title between them. Over Wilde's dedication and again before each part there is a small vignette. On the endpapers - both at the beginning and at the end of the book - the vision of the prisoner in his cell is represented. The main decorative design are 25 full-page illustrations (one of which is repeated on the wrapper). Of the three New York illustrators of the years 1927-8, Ward is, in spite of a certain academie stiffness, by far the most artistic, although he, | |

[pagina 20]

| |

too, lapses occasionally into theatrical pomposity. In his full-page prints he keeps slavishly to the text, and he always illustrates a passage appearing on the opposite page, so that it is easy, although there are no captions, to find the lines representedGa naar eindnoot102). In the same year as the editions illustrated by Vassos and by Ward, there appeared a further drawing from an entirely unexpected quarter. The Spanish translation published at Papayán in Columbia has an anonymous wrapper-design representing a gallows in the prison yard. The drawing, executed in an amateurish manner, is printed in red on white paper and pasted on the green wrapper. In 1932 the Antioch Press in Yellow Springs, Ohio, printed a quite attractive edition of the Ballad. Although purely typographical, it must be mentioned here on account of a vignette on the title page showing a nude male figure, with a gallows in the background. The artist's name is not given, and the illustration has no artistic merit. South America has provided another and richer contribution to our subject. In 1935 there appeared at Buenos Ayres Viau & Zona's edition de-luxe of Wilde's Selected Poems (the separate titles have been quoted in the list of Spanish translations, see note 50). The book contains a very large number of line-engravings after pen-drawings by Manuel Alfredo PachecoGa naar eindnoot103). The size is royal quarto and the production truly lavish. Yet as a whole the volume is rather disappointing because appearance and illustrations are still in the Jugendstil, which had been discarded in Europe twenty years earlier. The Ballad is decorated with 20 illustrations, in addition to a title vignette and five tail vignettes, one at the end of each part except the last. Besides there is an ornamental design of a tower, forming part of the half-title preceding each part, there is an ornament for the running headline on each page, and there is even one for the page numbers (the last-mentioned ornament being different for each poem in the book; for the Ballad it is a weight on a chain). It is a pity that from a formal point of view the artist had so little to say. His conception of the illustrator's task seems to be the right one: instead of slavishly keeping to the text, he paraphrases. But Pacheco was more felicitous in his ideas than in their realization. A few years later, a new edition of the Ballad appeared in New York. For its series of ‘Cameo Classics’, the well-known firm | |

[pagina 21]

| |

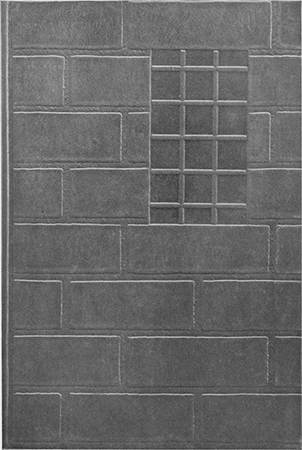

of Grosset & Dunlap had the Ballad illustrated with 20 full-page plates and four tail-vignettes (at the end of parts 1, 2, 4 and 5); the date of publication is not given, but is January 1937Ga naar eindnoot104). The illustrations consist of washed line-etchings and are signed ‘S.’; the unnamed artist is Alfred SkrenderGa naar eindnoot104). As in the American editions of the twenties, captions are printed under the plates. The decorations show technical skill but are somewhat conventional in idea and execution. Curiously enough, the edition has now become rare although it was printed in 6000 copiesGa naar eindnoot104) not so very long ago. It is more difficult to find than those illustrated by Vassos and by Ward, and rarer too than the edition of 1500 copies published by the Limited Editions ClubGa naar eindnoot105). The last mentioned edition appeared in the same year 1937. It was well printed by John S. Fass at the Harbor Press and contains nine full-page lithographs by Zhenya Gay. Of all illustrated editions of the Ballad this is doubtless the one most sought after by American collectors, owing to the fact that the books of the Limited Editions Club are not only collected by members of the club, but are also preferred by those amateurs who rely more on a familiar imprint than on their own taste. Moreover, this is the first American edition in which the illustrations are not reproduced photo-mechanically, but are printed from the original plates. From an artistic point of view, the lithographs are rather feeble and do not rise, either in idea or in form, above a very mediocre levelGa naar eindnoot106). All 1500 copies are signed by the artist and are bound in leather, the front cover being blindtooled with a design representing a wall with a barred window. In the first part of this study we have seen how the strain and stress of war had led to renewed interest being taken in the Ballad. The Second World War, in fact, not only gave rise in Holland to new translations: combining with the traditions of French bibliophilism, it brought forth in France a new crop of illustrated editions. The first of these, published in 1942 by the Librairie Marceau in Paris, contains a large number of coloured drawings by Dignimont, a well-known and prolific French illustrator. There are 7 full-page drawings (including the frontispiece), 8 on half-pages, and 27 smaller illustrations and vignettes, a total of 42 drawings. Dignimont's conception of his task is rather peculiar and unlike that of all other artists who have illustrated the Ballad. Instead of following the poet, who concentrates on intellectual | |

[pagina 22]

| |

Leather binding of the edition published by the Limited Editions Club, with lithographs by Zhenya Gay, New York, 1937. Original size 284 by 190 millimeters.

| |

[pagina 23]

| |

and psychological elements and who tells of the murder and its attendant circumstances no more than is quite indispensable, Dignimont depicts a crime that has taken place in the working-class quarter of a large town and arouses the lively interest of friends and neighbours. To find an illustration typical of his approach we need go no farther than the frontispiece: an everyday scene in a Street, with the prison in the background. Other such scenes not immediately suggested by the poem are quite frequent and result in a discord between text and illustrations: Wilde's words, sombre and laden with pain and horror, are made to go with drawings of a Southern vivacity and serenity, and for all their attractiveness as works of art, the illustrations are in no way imbued with the spirit that informs the BalladGa naar eindnoot107). The very opposite can be said of the other illustrated edition published in France during the war. The artist is once again Daragnès, and his new illustrations are no less impressive and successful than those he had made just over 25 years earlier. It may also have been the mood prevailing during the second World War which aroused in Daragnès the desire to illustrate the Ballad again, twenty-five years after his first edition, which had appeared during the first War. The new volume appeared at Easter 1944, printed on Daragnès' own press. The Ballad is in the original English, set in a large size of Didot Roman. The new illustrations are not cut in wood, but engraved in mezzotint. On the title page we see the murderer in the prison yard looking up to the sky; the engraving fills the page, leaving blank a rectangular panel, in which the title was overprinted by letterpressGa naar eindnoot108). In addition the volume contains six full-page illustrations: two prisoners with a warder walking in the yard; a prisoner standing in his cell; ten prisoners walking in the yard; the murderer asleep on his plank bed, guarded by a warder; the murderer who has raised himself to the window bars and looks out; the murderer walking up a narrow staircase to the executioner's shed. Besides the text is decorated with six vignettes, also in mezzotint, one at the beginning of each Part: the prisoner standing in his cell, reaching through the window bars, sitting at the table in his cell with the light from above, kneeling over his plank bed, sitting on the plank bed, and finally a bird's eye view of the whole prison. There is also a vignette on the jacket: a hand behind bars. This hand - the first motif to be seen by someone picking up | |

[pagina 24]

| |

the volume - has not been chosen without good reason. Just as Masereel twenty years earlier had been the first to illustrate the text by designing ever new variations on the person of the murderer, so Daragnès, in his new treatment of the Ballad, puts the emphasis on the murderer's hands. They are stressed again and again, and are given a new and different expression each time. By this means these illustrations acquire a character all their own. It goes without saying that the volume as a whole, with typography and illustrations designed by so serious an artist as Daragnès, is one of the finest editions of the Ballad. But even this fine book was pirated: as Wilde had died in 1900, his works were protected under French law at least until 1950. Thus it was the fate of the poem to be illegally reprinted, shortly before the expiration of the copyright, in the only civilized country in which the copyright in the translation had been fully honoured throughout its term. Immediately after the end of the Second World War, the translation by Marja was published in HollandGa naar eindnoot109). The ordinary edition of this translation has on the jacket a drawing of the barred window of the prison. This unsigned illustration, according to the publishers the work of Johan H. van Eikeren, is of no importance for a history of the illustrations to the poem. In the following year, 1946, a bilingual edition of the Ballad was published by Fernand Hazan, Paris. The English text is printed in red, in small italics, in the two inner top corners of each opening, surrounded by Davray's prose translation printed in black, in a larger size of Roman type: a layout similar to that usual in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries for texts with a commentary. The frontispiece, the only illustration in the book, is an etching by René Ben Sussan, a well-known illustrator of present-day France, who has contributed to many French de-luxe editions. It shows high prison walls with two barred Windows, a small speck of sky above; one looks down a shaft, but the prison yard, which must be at the bottom, cannot be seen. The book was printed on handmade paper in an edition of 1900 copiesGa naar eindnoot110). The first fully illustrated edition of the Ballad to appear after the Second World War was that published by the Peter Pauper Press, Mount Vernon, New York: The Ballad of Reading Gaol & Other Poems; with Wood Engravings by Hans Alexander Mueller. The slim volume contains forty poems in addition to the BalladGa naar eindnoot111), and is decorated with twelve illustrations, four of them | |

[pagina 25]

| |

to the Ballad and eight for other poemsGa naar eindnoot112). None of the woodengravings is full-page; the smallest are about a quarter page, the largest about half a page. At the beginning of the Ballad we see the prisoners' round in the yard, between the second and third Part the murderer on the gallows, between the third and fourth the prisoner lying down on his plank bed, and at the end the prisoner seated in his cell (repeated on the title page). The printing of the volume is - like that of all publications of the Peter Pauper Press - of a high standard, and Mueller's illustrations are attractive. The text is printed in black, the wood engravings in olive green; however one cannot help suspecting that the illustrations were printed not from the original wood but from line blocks or electros. Moreover, the relatively light colour does not show the designs to advantage; they would doubtless have come out better in black, but would then have appeared too heavy side by side with the rather light type used for the text. This the printer wished to avoid. Faced with the dilemma of a lack of balance between type and illustrations on the one hand and a reduced effect of the engravings on the other, the latter was preferred as the lesser evil, a solution unfavourable to Mueller's art, but probably advantageous to the book as a whole. We have now discussed no fewer than 28 different editions of Wilde's Ballad containing one or more illustrations, and not one of them was published in England. It was exactly fifty years after the poem was first published that the Castle Press brought out the first illustrated English edition in 1948. In the previous year the same firm had published The Picture of Dorian Gray as the first volume in the series of Wilde's Works with illustrationsGa naar eindnoot113); the Ballad is described as No. 2 of the series. It is illustrated by Arthur Wragg, who has also written a preface. This preface alone is enough to show how well Wragg has caught the spirit of the poem, for brief as it is it goes to the very heart of the work. Wragg was also, it is safe to assume, the only artist so conscientious in his preliminary studies that he went to visit Reading Gaol and Wilde's cell. Nor would it seem far-fetched to think that he was aware of the poet's negative attitude towards the possibilities of ‘realistic illustration’, for no artist, not even the expressionist Pankok, has kept so far away from realism in illustrating the Ballad as Wragg, whose drawings are decidedly surrealistic. We are today still so close to this style that we must beware of judging Wragg's illustrations; most of them appear | |

[pagina 26]

| |

Arthur Wragg. Pen drawing. From the edition published by the Castle Press, London, 1948. Original size.

| |

[pagina 27]

| |

to be rather forceful and impressive. There are a good many of them: on the jacket, on the endpaper, a title vignette, a border for the dedication, fourteen full-page and eighteen smaller illustrations, all drawn with the pen, but in a technique reminiscent of wood engravings. Wragg must have worked in close collaboration with the typographerGa naar eindnoot114), illustrations and type being very evenly balancedGa naar eindnoot115). The old saying that history does not repeat itself seems not to hold good in the world of books. We have seen that the hardships of war each time rekindled the interest in the text of Wilde's Ballad, while the revival of bibliophile editions in France during the years following the Second World War is comparable to that in Germany after the Great War. Six different editions of the Ballad had come out in Berlin and Munich between 1916 and 1923; five were published in Paris between 1942 and 1952. Of these, three have been discussed above, and two, published more recently, remain to be described. There are in France a number of clubs or societies formed for the purpose of producing at regular intervals fine illustrated books which are distributed to members only and are not for general sale. In the winter of 1950 -51, one of these societies, the ‘Bibliophiles et Graveurs d'Aujourd'hui’ (Booklovers and Engravers of Today) produced an edition of Davray's translation in 120 numbered copies on handmade Rives paper, 110 of them for its members and 10 for the artist and technical staff. The book is illustrated with 15 dry-point etchings by Robert Fonta: a frontispiece, 12 full-page etchings, a vignette at the beginning of the poem and one at the endGa naar eindnoot116). Although no expense was spared in the production, the edition is not to our liking, for while the artist's conception is in harmony with the spirit of the poem, his illustrations form too strong a contrast to the lavish production and to the expensive technique of original etchings. Fonta's belated post-expressionism lacks the force of Pankok's line-work, his hatching technique strikes us as petty, and his figures have no life, but are powerless marionettes. The most recent edition to be listed is that published by the Editions de l'Odéon and illustrated by Tavy Norton. The artist, who belongs to the younger generation, is the son of a French father and an Annamite mother - indeed, one French critic thought he could detect in Notton's line-work the heritage of Far Eastern suppleness. Norton does not belong to the avant-garde, like | |

[pagina 28]

| |

Picasso and Derain; his dry-point etchings are entirely traditional and naturalistic. But given these limits, his work is good and - the word suggests itself - conscientious. He has mastered the technique and has gone far towards entering into the spirit of the Ballad and Wilde's emotions while he was serving his sentence. Yet his etchings do not ding slavishly to the text, but succeed in reflecting the ideas of the poem. The sizable volume (32,5 × 23,5 cm) is printed beautifully in 24 point Garamond, the translation is, as usual, Davray's. Six full-page illustrations (including the frontispiece), one doublepage etching, and six of smaller size, extending over half or three quarters of a page, accompany the French text; the English original, which is appended at the end of each section, is not illustrated. The book is printed on handmade Rives paper in an edition of 200 copies, of which the first 60 contain a suite apart of the etchings with remarques. These prints are interesting and deserve special mentionGa naar eindnoot117). Remarques, as is well known, is the name given to small sketches which some artists draw in the margin of a plate and which are omitted when the edition is printed. Notton, however, has taken the term literally (‘remarks’), adding on each plate a number of more or less short comments, which were etched in. Most of them are quotations from Wilde's ‘De Profundis’, a few are from other sources: from the poet's articles on prison life, from Martin's report on the poet in prison (in Sherard's ‘The Life of Oscar Wilde’), and from Thomas's ‘L'esprit d'Oscar Wilde’. They are clear evidence of how earnestly Notton strove to understand Wilde's personality and emotions while in prison. As there is no room here to analyse all of the etchings with their remarques, we shall restrict ourselves to one example, which is short, but typical. One of Notton's illustrations to Part V of the Ballad is a full-page etching of Christ as Man of Sorrows, seated on a stone, His body covered with weals, the crown of thorns on His head. Above and at the left (running upward) are two quotations from ‘De Profundis’; one of them reads: ‘La place de Christ est, certes, avec les poètes. Sa conception de l'Humanité provenait tout droit de l'imagination qui seule peut la comprendre’ (Christ's place indeed is with the poets. His whole conception of humanity sprang right out of the imagination and can only be realised by it). Having discussed the printed illustrations to the Ballad, we must conclude by mentioning one edition illustrated otherwise than | |

[pagina 29]

| |

with reproductions. It is listed as lot 118 in the sale catalogue of the Anderson Galleries, New York, 23 April 1920 (No. 1484, The Oscar Wilde Collection of John B. Stetson Jr., Elkins Park, Pa.). As I have not seen the copy, and do not know who has acquired it, I think it best to quote the description given in the sale catalogue. The text is apparently one of the undated editions published by Brentano before 1904, as the later editions are all dated. ‘(The Ballad of Reading Gaol.) Each leaf inlaid to 4to, full brown levant morocco; the front cover contains an inlaid panel of gray levant morocco, on which is depicted with inlays of different colored moroccos and gilt tooling, the interior of a prison yard, with convicts marching; the compartments on the back are emblematically tooled and inlaid with a dagger thrust through a red heart; the front doublure of a darker shade of levant morocco has outlined in gold, the figure of a prisoner kneeling beside his cot in the cell; the back doublure has a spider's web in gold on dark brown levant morocco: pale blue silk flys, gilt edges, in slip case.

New York: Brentano, n.d. Extra illustrated by the insertion of 23 original drawings, in wash, pen-and-ink, and color, by McDougall, George Gibbs, Isabel Lyndall, Dwiggins, P.V. Wilson, H.S. Pullinger, M.C. Craven, J.L.G. Ferris, and others, all American artists. The front cover decoration is after the drawing by T.R. Shaver; the front doublure after the drawing by Gibbs; the emblems on the back after the drawing by Dwiggins, and the back doublure after McDougall.’ We have now reached the end of our long list of illustrations to the Ballad, a list of 31 different editions, spread over 45 years, over two continents and eight countries. Our catalogue comprises all manner of books, from the pamphlet with a trivial vignette to the extravagantly lavish publication containing on each page an original etching; from cheap editions printed in thousands of copies to the expensive edition de-luxe worth hundreds of dollars. Illustrators of every rank have tried their hand at the poem: men whose very names are not recorded, second-rate graphic artists long since forgotten, and artists of world renown. Each of them has striven in his own way to grapple with the problem facing him. This only is common to all: however different their period, origin, intellectual outlook and artistic temperament, they all succumbed to the spell of the great poem, which has never and nowhere ceased to appeal to the noblest emotions of humanity. | |

[pagina 37]

| |

|

|