Folium Librorum Vitae Deditum. Jaargang 2

(1952)– [tijdschrift] Folium–

[pagina 113]

| |

[Nummer 5-6] | |

Oscar Wilde's Ballad of Reading Gaol

| |

[pagina 114]

| |

sity Library of Prague, through whose help I received a Czech edition of the Ballad not otherwise obtainable in Western Europe. My sincere gratitude is due to all those mentioned. | |

IEver since it was first published, Oscar Wilde's Ballad of Reading Gaol has appealed strongly to those susceptible to the charms of this genre. The theme is perpetually topical: wantonly tortured and ill-treated in the name of a doubtful justice, the victim - surely no less God's creature than the hangman, the sheriff and the judge - voices his lament. It is rendered in a form that never fails to affect an open-minded reader, even though historians of literature can trace back some of its elements to earlier examples. The Ballad was received in England with great enthusiasm and enjoyed an extraordinary success from the very date of its publication - a success that must be rated all the more highly as the book came out only six months after Wilde's release from gaol, at a time when not only his works but his very name were taboo in EnglandGa naar eindnoot1). That this success in England cannot be ascribed to mere sensationalism is shown by the impression the Ballad made abroad - which will be dealt with below - but also by the judgments passed upon it by the leading critics and writers of the day. Shortly after its publication, no less a man than Arthur Symons devoted nearly two quarto columns to a reviewGa naar eindnoot2) in which he called the Ballad ‘this very powerful piece of writing’ - a judgment that still holds good. A few years later, enthusiastic praise was bestowed upon it by the very influential Lady CurrieGa naar eindnoot3), who went so far as to put some parts of the Ballad on a level with the descriptions in Dante's Inferno, but thought the Ballad infinitely more human. One of Wilde's earliest biographers, Leonard Croswell Ingleby, ranks it highest in the ballad literature of the whole worldGa naar eindnoot4). Fifteen years after it was published, Holbrook Jackson described the work as a creation ‘which bears every indication of permanence’ and added: ‘Had the Ballad been written a hundred years ago, it would have been printed as a broadsheet and sold in the streets by the balladmongers; it is so common and so great as that’Ga naar eindnoot5). Arthur Ransome praises its poetical power; he knows of no other poem that so intensifies our horror of mortalityGa naar eindnoot6). | |

[pagina 115]

| |

For Frank Harris it is by far the most powerful ballad in the whole of English poetryGa naar eindnoot7), for John Cowper Powys the best tragical ballad since Coleridge's ‘Ancient Mariner’Ga naar eindnoot8). Martin Birnbaum calls it ‘one of the most perfect poems of its kind’Ga naar eindnoot9), Monahan ‘the best fruit of Wilde's talent - indeed the one work that has united all suffrages’Ga naar eindnoot10). The most extravagant praise of all was bestowed on it by Boris Brasol: ‘Original all through and as an indictment of capital punishment it ranks with such a heartbreaking story as Andreev's The Seven that were hanged’ or Prince Mishkin's unforgettable account, in ‘The Idiot’, of the confused feelings of a man sentenced to die... The grim realism of the Ballad, despite the limitations inherent in poetry, is as powerful as that achieved by Zola in ‘Germinal’ or by Tolstoy in ‘The Death of Ivan Ilyich’Ga naar eindnoot11). A little later, Frances Winwar expresses herself with hardly less enthusiasm: ‘In the heart-wrung stanzas of the Ballad he attained the peak of his poetic achievement. Higher he could not go: there was no greater elevation’Ga naar eindnoot12). Even writers critical of Wilde's poetry make an exception in favour of the Ballad. Among them are Lord Alfred Douglas, who condemns all Wilde's other poems but praises the BalladGa naar eindnoot13), and Burton Roscoe, who has few kind words for Wilde's work but cannot help remarking: ‘The Ballad of Reading Gaol has already taken its place among the imperishable ballads of a literature rich in ballads’Ga naar eindnoot14). Critical opinion outside the English-speaking countries was equally enthusiastic. I cannot claim to have collected all the relevant passages systematically, but the following examples may suffice. Shortly after the French translation was published, Octave Uzanne wrote a review of three pagesGa naar eindnoot15). About thirty years later, André Maurois called the Ballad ‘a really very fine piece of work’Ga naar eindnoot16), and Léon Lemonnier refers to it as Wilde's masterpiece, ‘of grandiose simplicity’Ga naar eindnoot17). In Germany Bernhard Fehr devoted to it a separate chapter of 14 pages in his ‘Studien zu Oscar Wildes Gedichten’Ga naar eindnoot18). Like a good many other critics, he emphasizes that here Wilde did not treat a literary theme but gave poetic expression to a real experience. From the Spanishspeaking world I quote Alvaro Alcala GalianoGa naar eindnoot19): ‘a tense and vigorous realism runs through the terrifying stanzas of his macabre Ballad, which deserves to be included in all anthologies... Never before had Wilde roused such a fever of excitement in the reader’. Jorge Luis BorgesGa naar eindnoot20) finds in the Ballad the highest poetical | |

[pagina 116]

| |

merit and declares that every reader is moved and carried away by it. In the Netherlands, Mrs. K.C. Boxmann-Winkler devoted a separate study to ‘De Profundis’ and the BalladGa naar eindnoot21); she calls the Ballad ‘the most marvellous poem Wilde ever wrote’ and speaks of its power and originality and of its ‘almost perfect purified tranquillity’. In Brazil, P. Balmaceda Cardoso calls it an admirable poemGa naar eindnoot22); in Poland, S.J. Imber claims that the Ballad has obtained a lasting place among the poems expressing human suffering; he extols its power of expression, the loftiness of its sentiments, and the consummate beauty of formGa naar eindnoot23). Konstantin Balmont, the eminent Russian lyric poet who translated the Ballad, declares that in it Wilde has pictured the horrors of imprisonment and the absurdity of capital punishment with a power unattained by any European poet before himGa naar eindnoot24). The well-known critic and essayist Evgeni Anickov speaks of its solemn simplicity and points to the harmony between profound thought and suffering and to its melody of charity and horrorGa naar eindnoot25). The best and most extensive analysis of the work is that of the Frenchman Robert Merle in his monograph on WildeGa naar eindnoot26). He too regards the Ballad as Wilde's masterpiece and devotes to it a separate chapter (p. 411-72). Against this international chorus of praise I have come across only two unfavourable opinions: one pronounced, shortly after the book came out, by Wilde's contemporary, the poet J. HenleyGa naar eindnoot27), who is now almost forgotten, the other an analysis by Mario VinciguerraGa naar eindnoot28), who slashes the Ballad to shreds. When Wilde was released from prison in May 1897, he crossed the Channel and settled in June at Berneval near Dieppe on the north coast of France. He must have set to work on the Ballad at once, for as early as July it is mentioned in his correspondenceGa naar eindnoot29). On 24 August 1897 he sent to his publisher Leonard Smithers the first part of the manuscript to be copied; the rest followed in October from Naples, whither Lord Alfred Douglas had called him. The book was published on 13 February 1898 (copyright dated January 1898), beautifully printed on handmade paper, in a limited edition of 830 copies (‘of this Edition eight hundred copies have been printed on hand-made paper, and thirty copies on Japanese vellum’). This first edition was sold out almost overnight, the book was reprinted in the same month, and by June 1899, no fewer than seven editions had appearedGa naar eindnoot30). At this stage something extraordinary began to enter into | |

[pagina 117]

| |

the history of the book. Smithers, its publisher, a man of no common personality and of more than average intellectual abilities and interests, was closely connected with the literary London of the ninetiesGa naar eindnoot31). But in the long run his success in business bore no relation to his abilities, and his morals as a publisher were not of the highest. Nor would Wilde have chosen him had his choice been quite free: but his friend Robert Ross tells us that no other publisher could be found - and indeed, which firm of repute could have dared to lend its imprint to a book by the notorious author? In 1898 Smithers was in bad financial circumstances (he was later declared bankrupt), and after Wilde's death in 1900 he proceeded to bring out one edition after the other, all with the date 1898, in order to cheat the heirs out of their royalties. He may have profited from the fact that the poet's inheritance proved a very complicated matter: since the trial, Wilde's estate had been administered under the bankruptcy laws; in fact, the proceedings took about twelve years and it was not until 1908 that his heirs recovered control of the inheritance. The publishing rights of the Ballad - and of the other poems - were transferred to the well-known firm of Methuen, and within a few years several further editions appeared. In 1911 Wilde's poems, including the Ballad, were collected in one volume and published im Methuen's popular ‘Shilling Library’Ga naar eindnoot32); thenceforth they were reprinted in this form, and there was no longer any need for a separate edition of the BalladGa naar eindnoot33). It was only towards and after the end of the second World War that the need for a new separate edition of the Ballad made itself felt in England. In 1944 the Unicorn Press in London published a small, cheap edition, followed by a second and third printing in 1945, a fourth in 1946 and a fifth in 1948. At the same time as the lastmentioned edition, the Castle Press brought out its edition of the works of Oscar Wilde, in which the Ballad is accompanied by the impressive illustrations of Arthur Wragg, which will be dealt with more fully in the discussion of the illustrated editions below. While he was engaged in preparing the English edition, Smithers had been negotiating with Elizabeth Marbury, a literary agent in New York, with a view to selling the U.S.A. rights. This proved to be harder than she had expected, and it was with difficulty that she managed to obtain $ 100 for the publication | |

[pagina 118]

| |

of the poem in ‘The Journal’Ga naar eindnoot34). But Smithers neglected to comply with the copyright formalities required by American law, and the poem was not protected in the United States. The enormous success of the Ballad in the U.S.A. is evident from the fact that it was reprinted innumerable times. In the appendix to this essay I have listed the editions I have been able to identify. There are likely to be others, but they are very hard to trace, consisting as they do of cheap little books, which are not mentioned even in the Cumulative Book Index; even in a country of more conservative outlook than the United States, such booklets would hardly have been preserved. There are still more proofs of the popularity of Wilde and his Ballad on the other side of the Atlantic. The two largest Wilde collections were formed in the United States: that of John B. StetsonGa naar eindnoot35), now sold, contained the only preserved fragment of the manuscript, the proof sheets dated 1897, three copies of the first edition (one with an autograph letter from Wilde to Smithers, another with a dedication to Max Beerbohm, the third in the special edition on Japan paper), the first American edition in book form, and finally a special copy containing 23 original drawings (a description of this copy will follow in the list of illustrated editions below). The other large collection is that of W.A. Clark Jr., now belonging to the University of California Library and described in a five-volume catalogueGa naar eindnoot36). Apart from the original British editions, this catalogue lists 19 American reprints. The history of the Ballad's origin has been told twice in the U.S.A.: by Richard Butler GlaenzerGa naar eindnoot37) and by John WinterichGa naar eindnoot38), though the latter speaks more about Wilde's life than about the poem. Most of the illustrated editions of the work have appeared in the United States. Considering Wilde's close relations to Parisian authors and French literature (strangely enough it is not generally known that his Salome was first written and published in French), it is not surprising that a French translation should have appeared only a few months after the first English edition. The French prefer to read foreign poetry in prose translations, and hence the translation of Henry D. Davray, made under the supervision of, and in collaboration with, the author and published in the Mercure de France of May 1898, is not in verse form. Of course the rhythmic character of the original is lost, but this very example proves that a good prose translation can do justice to the quality of the | |

[pagina 119]

| |

Title page of the first American edition (original size)

| |

[pagina 120]

| |

original and even claim poetic merit, while avoiding the dangers arising from rhyme. Many years later Davray wrote about his collaboration with Wilde, and I shall come back to this. His translation ranks as a classic feat; from 1898 to 1948 it was frequently reprinted, and a new de-luxe edition of it (without illustrations) appeared as late as 1944Ga naar eindnoot39). In the same year there appeared in Brussels a reprint of Davray's translation with his preface, the only Belgian edition of the Ballad known to me. Once Davray's translation had been published, French copyright regulations made another edition impossible for many years. Even after the expiry of the copyright protection, no one else attempted to translate the poem because the high literary quality of Davray's version, and probably also the lustre shed on it by the collaboration of Wilde himself, had given it a permanent place in French literature. But the Ballad was no less valued and popular in France, as is shown by the many reprints of Davray's text and by the numerous illustrated de luxe editions, which will be discussed below. Even French musicians made use of the Ballad: the composer Jacques Ibert (born 1890) published in 1921 a symphonic poem entitled La Ballade du Geôle de Reading. So simple things are in France, so complicated are they in Germany. No German translation of the Ballad published in the first few years after 1898 has come to my knowledge, and none is listed as a separate publication in the bibliographical reference works. In 1903 the Inselverlag brought out the first German translation, by Wilhelm Schoelermann, in a limited edition of 300 numbered copies, followed in 1904, 1905 and 1907 by a second, third and fourth edition. Was this publication authorized? Hardly. Not only because there is no mention of any authorization in the book, but also because the other translations which appeared shortly afterwards were allowed to go unchallenged; and as the Inselverlag has always guarded its rights jealously, it is fair to assume that it possessed no rights in the Ballad which it could have asserted. I was not referring to the translation by George Sylvester Viereck which, though made in New York as early as 1904, was not published until 1922Ga naar eindnoot40). In 1906, however, the Max Hesse Verlag of Leipzig brought out a translation by O.A. SchröderGa naar eindnoot41) with an explanatory introduction of 38 pages. This introduction, in spite of a certain dryness and pedantry, was not without merits at the time, but subsequent literary and biographical researches | |

[pagina 121]

| |

have rendered it rather obsolete. In the same year, Wilde's Collected Works came out in the Wiener Verlag; the first volume contains the poems, translated by Otto Hauser, among them the BalladGa naar eindnoot42). A year later, in 1907, the ‘authorized’ translation by Walther Unus appeared as No. 4864 of Reclam's ‘Universal-Bibliothek’ (reprinted in 1926), in 1910 Eduard Thorn's translation was published by Bruns of Minden. In 1916 Axel Juncker in Berlin brought out a translation by Arthur Holitscher as one of the series of ‘Orplid-Bücher’ (with illustrations by Schmalhausen; new edition 1920); in the following year, 1917, two new translations came out: Felix Grafe's in the HyperionverlagGa naar eindnoot43), with af frontispiece by Kubin, and Albrecht Schaeffer'sGa naar eindnoot43a) as an ‘Inselbuch’ (No. 220). How was it possible that within 14 years no fewer than nine different German translations could appear of a work protected

German translation by F. Grafe. 2nd edition, 1920. Cover design by Emil Prectorius (Original size)

| |

[pagina 122]

| |

German translation bij F. Grafe. First edition (1918), Frontispiece bij A. Kubin. (Original size)

| |

[pagina 123]

| |

by copyright? The legal position was quite clear. The Berne Convention of 1886 (art. 5, 1), the German copyright law of 1901 (art. 12)Ga naar eindnoot44), and the revised Berne Convention of 1908 (art. 8), all prohibited the printing of a translation of the Ballad without the permission of whoever controlled the English rights, whether the publisher or the author's heirsGa naar eindnoot45). Of all German translations only the Reclam edition claimed to be authorized. It appeared in 1907, that is before the expiration of the 10 years which then protected a translation. Hence any other translation would have constituted an infringement of Reclam's rights. But as nothing is known of a protest by this firm against any of the numerous subsequent translations, it is fair to assume that there was something dubious about the so-called authorization. The other eight translations did not even pretend to any appearance of legality. How it was possible that reputable firms did not scruple to publish the Ballad in disregard of the copyright it is hard to say. The explanation lies perhaps in the complications attending Wilde's inheritance, as already mentioned; when his heirs regained control of the rights in 1908, the ten-year period of protection had elapsed and this was probably why they did not trouble themselves about any earlier offending translations. However that may be, no stronger proof can be conceived of the effect the Ballad had in Germany than the fact that so many translations were made, most of them running into several editions. I know of no equally successful poem in modern literature, and even of older poetry only such epoch-making works as Dante's Divina Commedia and Shakespeare's Sonnets have been translated so frequently; the translations of these works, however, were spread over long periods of time and not made in the brief span of less than fifteen years. It is not my object here to analyse all these translations and to draw comparisons between them: this is a bibliographical and not a literary study. All I will say is this: each translation has its strong and its weak points and none is so outstanding that it deserves to be given special prominence. But there is one that does not appeal to me: Holitscher's attempt to replace the rhythm of the original by doggerellike verse suggesting the tone of the German folk-ballad remains to me unconvincing. I cannot help feeling that this translation does not do justice to the English original and is a failure. Apart from the published German translations, there are some | |

[pagina 124]

| |

that have never been printed. The poet Karl August Klein, of Hamburg, who was connected with the circle around Stefan George, has made a translation of which I have a copy; made in his old age, not long before his death in the spring of 1952, it does not belong to his best work and seems to me to be unsuccessful. On 28 January 1951, the Nordwestdeutsche Rundfunk in Hamburg broadcast a new translation by Ralf Rudolf Rudeloff. He very kindly sent me a typescript of his translation, which is of high quality and is in no way inferior to the earlier translations. It is to be regretted that it has not been published so far, as it certainly merits being known more widely. Though German is not the only language in which there is more than one translation, no other language can boast the same number. Still, there are no fewer than at least seven versions in Spanish, five in Italian, and five in Dutch. Only ten months after the first English edition, a Spanish translation from the hand of Dario HerreraGa naar eindnoot46) appeared in the Argentinian review ‘El Mercurio Americano’. The Spanish mother-country did not follow until ten years later with the version of Ricardo Baeza, which appeared in the periodical ‘Prometeo’ in 1909Ga naar eindnoot47) and was published in bookform in 1911 by Lelénica of Madrid. The next translation, that of Jacinto Càrdenas, was published in 1925 in the Argentinian periodical ‘Nosotros’Ga naar eindnoot48), and subsequently in bookform (Buenos Ayres, n.d.). In the small town of Papayán in Columbia, Guillermo ValenciaGa naar eindnoot49) published a new translation in 1932. Two years later there followed a costly edition de luxe of Wilde's Selected PoemsGa naar eindnoot50), for which the Ballad was translated by Mariano de Vedia y Mitra in collaboration with Luis Maria Diaz Carvalho. A more recent translation into Spanish is by the well-known writer J. Gómez de la Serna; it appeared first in Wilde's Collected Works (vol. 6) published in 1943Ga naar eindnoot51)), and was reprinted later in a separate volume by Bruguera in BercelonaGa naar eindnoot52). The most recent translation into Spanish appeared in 1946; it is by León Mirlas and is included in an anthology from Wilde's poetry published by the Espasa-Calpe Argentina in Buenos Aires in the popular series Collección Austral. A further Spanish translation appeared in 1916 as No. 7 of the ‘Ediciones Mínimas’ in Buenos Aires. A copy of this edition is in the Biblioteca Nacional of Buenos Aires, but not, as far as I was able to ascertain, in any Library in Europe or North America. | |

[pagina 125]

| |

The translator's name is not mentioned in this edition and hence I could not determine whether it is a reprint of an earlier translation or a new one. Like the earliest Spanish translation, the earliest Italian one, that of Giuseppe Vannicola, appeared first in a periodicalGa naar eindnoot53). Later it was published by the firm of Bernardo Lux in Rome as a book, with a preface by André Gide. Whether the undated translation by G. Fracsa de Naro came before or after the one just mentioned I cannot sayGa naar eindnoot54). In 1920 followed Carlo Vallin's translation in Milan; in 1922 Lorenzo Borri's at Pistoia, and finally Adeline Manzotti-Brignone's translation, which was published, undated, in 1926 by Bolla in Milan, together with De Profundis. Her version of the Ballad was reprinted in the second volume of Wilde's works (‘Opere’, ibidem, 1948). The first translation into Dutch was Chr. van Balen'sGa naar eindnoot55), followed by the versions of Hendrik van der Wal (1919)Ga naar eindnoot56) and Leo van Breen (1930)Ga naar eindnoot57). During the last war there appeared two ‘illegal’ editions: a reprint of van der Wal's versionGa naar eindnoot58) and a new translation by Eduard VerkadeGa naar eindnoot59). Finally there is a remarkable translation by A. MarjaGa naar eindnoot60), published by F.G. Kroonder at Bussum in 1945. It is not in literary Dutch, but in thieves' slang (‘bargoens’). Whereas Wilde expresses the feelings of the prisoner at the execution of his fellow-prisoner in highly cultivated language, Marja puts them into the mouth of a common criminal using his uncouth speech. It might be expected that an overbold attempt of this kind must fail to do justice to the decadent elegance of Wilde's style. Surprisingly enough this is not so. The ideas, the rhythm, and even the rhyme scheme of the original are rendered faithfully and I have no hesitation in describing Marja's translation as one of the most successful I know. It was no mere coincidence that during the years 1944 and 1945 three editions of the Ballad appeared in the Netherlands. During the German occupation the theme was specially topical, and it is a proof of the artistic merits of the poem that nearly fifty years after its completion it was felt to be an adequate expression of contemporary problems. There exists a further Dutch translation, which has never been published: the well-known poet M. Nijhoff (born in 1894) translated the Ballad when he was still quite young. But he appears not to value it any longer, for in reply to my enquiry he wrote that he could not lay his hands on it, but would let me know if | |

[pagina 126]

| |

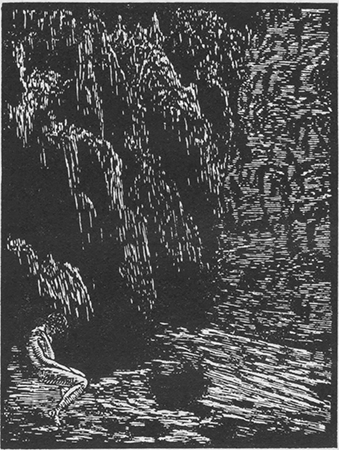

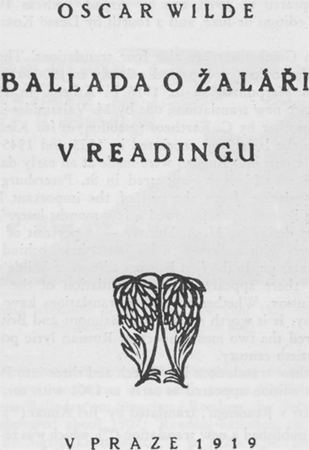

Frontispiece and title of the Czech translation by J. Zivny. Prague, 1919. Woodcut by Fr. Kobliha. (Original size). The words ‘Bailada o Zalari v Rekdingu’ are printed in red.

| |

[pagina 127]

| |

| |

[pagina 128]

| |

he should come across it. The first Hungarian translation, by Antal Radó, did not appear until 1908, probably owing to copyright regulations. In the Austrian-Hungarian Empire, as in Germany, the poem was protected by copyright for ten years, and it seems therefore more than a coincidence that the first Hungarian translation appeared immediately after the expiry of that period. It was twice reprinted in Wilde's Collected Works. A new translation by József Szebenyei appeared in 1912, one by Arpád Tóth in 1921 as an illustrated edition de-luxe, and a fourth by Dezsö Kosztolányi in 1928Ga naar eindnoot61). In modern Greek there are also four translations. The first, by D.P. TankopoulosGa naar eindnoot62) appeared as early as 1906, the next, by Alexandros Marponzoglou in 1916 in Athens. In 1919 there appeared two new translations, one by M. Valsamides in Alexandria and another by C. Kartheos (pseudonym for Kleon Lakon) in Athens; the latter was reprinted in 1923 and 1945. Two translations into Russian were made at an early date: a very faithful one, by N. Kern, appeared in St. Petersburg in 1903; a freer translation, from the pen of the important lyric poet Konstantin BalmontGa naar eindnoot63), followed a few months later. The latter has a cover design by M.A. Durnov - a portrait of Wilde, in evening dress with a flower in his buttonhole, behind a barred window. Later on, in the first Russian edition of Wilde's collected worksGa naar eindnoot64), there appeared a new translation of the Ballad by Valerij Briussov. Whether any other translations have appeared I cannot say. It is worth noting that Balmont and Briussov may be considered the two most important Russian lyric poets of the early twentieth century. There are three translations into Czech and three into Polish. The first Czech edition appeared as early as 1901 with the title ‘Ballada o žaláři v Readingu’, translated by Jiří AlmarGa naar eindnoot65). In 1909, Jiri Zivny published a new translationGa naar eindnoot66), which was re-issued ten years later by the original publishers in a de-luxe editionGa naar eindnoot67). Lastly there appeared a new translation bij Frantìšek Vrba a few years agoGa naar eindnoot68). Three Hebrew translations have come to my notice. The only one that has been printed in full is that by Hanania Reichman in his book ‘Mi-Shirat Ha-Olam’ (From the World's Poetry), published 1942 by Yavne, Tel-Aviv, pp. 105-177. Fragments of a | |

[pagina 129]

| |

translation by S. Bass were printed in the monthly ‘M'oznayim’, XII, 1941, pp. 159 ff. Whether Bass has translated the entire Ballad I do not know. It was certainly translated in full by Jacob Garland, but only the first part has so far been published (in the daily paper ‘Davar’, Tel-Aviv, No. 6690, 18 July 1947). It was not until 1911 that the first Polish edition came out, a translation by Andrzej TretiakGa naar eindnoot69). This was thrown into the shade by that of the most important modern Polish poet Jan Kasprowicz, which appeared in 1923Ga naar eindnoot70).

Yiddish translation by A. Karlin. New York. 1925. Cover design by Z. Maod. (Original size)

In 1927, Piotr Lucjan Slucki printed a new translation at Siedlce for private circulation only. There exist two translations in Swedish, two in Yiddish, and two in Bulgarian. ‘Balladen om fängelset i Reading’, by Bertel GripenbergGa naar eindnoot71), appeared about 1907; ‘Reading-balladen, en sång från fängelset, by Sigrid LidströmerGa naar eindnoot72), in 1920. The first Yiddish translation of the Ballad - about 1906 - is by H. RosenblattGa naar eindnoot73), the other - of 1925 - by A. KarlinGa naar eindnoot74). In Bulgarian a prose rendering was published by E.A. MindovGa naar eindnoot75) about 1912-3 and a verse translation by Chr. Siljanov in 1920Ga naar eindnoot76). In other European languages I have been able to find the following translations: Danish by Oskar V. AndersenGa naar eindnoot77), 1910 (three editions); Serbian by Svetislav Stefanovic in 1923Ga naar eindnoot78); White-Rus- | |

[pagina 130]

| |

sian by Mihas Dubrouski in 1926Ga naar eindnoot79); Finnish by Yrjö Jylhä in 1929Ga naar eindnoot80); and finally Portuguese (together with ‘De Profundis’) by Januario LeiteGa naar eindnoot81) [1946]. The National Library in Ankara informed me that there is no translation into Turkish. Unfortunately I was unable to obtain information from some countries behind the Iron Curtain. I regret especially that I had no reply to my enquiry from the Lenin Library in Moscow and hence I cannot say whether there are further translations into Russian except those already mentioned and whether there are any in the other languages represented in the Soviet Union. The enquiries I adressed to Bucharest, to Zagreb and to Tirana have likewise remained unanswered. Non-European languages are not included in my researches because I cannot read any of them. But it may be mentioned that there are two Japanese translations of the Ballad; the first, by Hinatsu Kainosuke, appeared in 1923 in volume 4 of Wilde's Collected Works (reprinted in 1936 and 1950); the other, by Teiichi Hirai, in a edition of Selected Works by Wilde (date of publication not known)Ga naar eindnoot82).

(Will be continued). |

|