Burgerhartlezing 2013. The Sense of Justice. A Realistic Utopia?

(2013)–Céline Spector, [tijdschrift] Burgerhartlezing, [tijdschrift] Documentatieblad werkgroep Achttiende eeuw–

[pagina 7]

| |

The Sense of Justice. A Realistic Utopia?

| |

[pagina 8]

| |

blican concept of citizenship. Why Rousseau? A full theory of citizenship requires an analysis of the reasons why one should prefer, in a liberal society, to defend just institutions, even when these institutions ask for sacrifices in terms of narrow self-interest. In John Rawls' influential work (A Theory of Justice, 1971), the ‘sense of justice’ defined as the desire to defend just institutions is the basis of a ‘realistic utopia’. At the heart of Rawls' theory of citizenship, the sense of justice prevents citizens from giving into the temptation of ‘free riding’ (taking benefits from social institutions without contributing fairly) and promotes a genuine sense of cooperation and fair play.

So what is left from the Enlightenment today? After a quick historical inquiry about the ‘revolution of citizenship’ which took place in the eighteenth century around the 1750-1760s, I will focus on two major ‘philosophes’, who contributed more than any others to this ‘revolution’ before the French Revolution. The former is usually considered as a liberal (MontesquieuGa naar voetnoot4); the latter is often regarded as one of the most important pre-revolutionary republican thinkers (Rousseau). In the last section of my talk, I will show how their respective depictions of the ethos of citizenship, associated with liberty and equality, is still at work in contemporary political theory. | |

I. Citizen or Bourgeois? From legal status to political agencyLike other terms associated with the development of a secular national consciousness (nation, patrie and patriote), the term citoyen became more and more frequent from the 1750s on. The Encyclopédie of Diderot and d'Alembert gives a hint of this process. In the first half of the century, different words were used to describe the inhabitants of the kingdom of France (including the old term regnicole): habitants and bourgeois referred more directly to place of residence, and the term sujet was much in use in the context of the absolute monarchy. But in Diderot's entry, the citizen is contrasted with the habitant and with the bourgeois. Under certain conditions only may the bourgeois become a citizen: BOURGEOIS, CITOYEN, HABITANT [Grammaire] | |

[pagina 9]

| |

les intérêts de sa ville contre les attentats qui la menacent, en devient citoyen. Les hommes sont habitans de la terre. Les villes sont pleines de bourgeois; il y a peu de citoyens parmi ces bourgeois. L'habitation suppose un lieu; la bourgeoisie suppose une ville; la qualité de citoyen, une société dont chaque particulier connoît les affaires & aime le bien, & peut se promettre de parvenir aux premières dignités.Ga naar voetnoot5 [terms relating to one's residence in a Place. The burgher is one whose ordinary residence is in a city; the citizen is a burgher whose position is related to the society of which he is a member, and the inhabitant is a person in particular relation to his residence pure & simple. One is an inhabitant of the city, the province or the country: one is a burgher of Paris. The burghers of Paris who take to heart the interests of their city against threatening attacks, have thereby become citizens. Men are inhabitants of the earth. The cities are full of burghers; there are few citizens among the burghers. Habitation requires a place, the burgher requires a city; the qualification of citizen needs a society in which each knows its customs & loves the good, & may epect to achieve the essential dignities.] According to the historian Peter Sahlins,Ga naar voetnoot6 Diderot's entry in the Encyclopédie followed the famous definition by the French legal theorist Jean Bodin in assuming that the citizen was something else than the ‘honorary citizen’ of a particular town or city. But unlike Bodin, Diderot did not frame his argument around the legal distinctions between citizens and foreigners. The entry ‘citizen’ did not presume a socially inclusive category of ‘nationals’ that stood opposed to ‘aliens’. Diderot identified a narrower category of rights-bearing subjects, members of civil society: ‘He who is a member of a free society (made up) of several families; who partakes of the rights of society, and enjoys its liberties (franchises)’. P. Sahlins argues that Diderot's definition broke dramatically with traditional French legal culture: the king was no longer cast as a paternal or absolute source of citizenship; rather, it was society itself (civil society) that conferred rights and obligations on its members. On his passing remarks on naturalization, Diderot argued that ‘naturalized citizens’ and not ‘naturalized foreigners’ were defined as ‘those to whom society has accorded participation in its rights and liberties although they are not born in its midst’.

Other historians share this conception of the Enlightenment revolution of citizenship. Focusing on France, Elizabeth Rechniewski identifies at least three broad trends in the evolution of the conception of the citizen in the second half of the eighteenth century: secularization, moralization, and democratization.Ga naar voetnoot7 First, the secularization of | |

[pagina 10]

| |

the citizen: in the course of the eighteenth century, the link between Catholicism and citizenship became gradually looser, and eventually so weak that the Declaration of 1787 restored civil status to the Protestants (the same happened a little later with the Jews).Ga naar voetnoot8 Second, the moralization of the citizen: the new yardstick was usefulness to the nation, ‘utilité publique’. At a time very much critical of a frivolous court and of an aristocratic-dominated society whose ‘moeurs’ were dictated by women and whose aim was to please, a virile, masculine ideal of citizenship fostered. Last but not least, the democratization of citizenship, associated to its individualization: the citizen was not defined either by birth or by social status any more. Nevertheless, the political dimension is certainly the most salient one. According to Peter Sahlins' groundbreaking work Unnaturally French: Foreign Citizens in the Old Regime and After,Ga naar voetnoot9 the citizenship revolution of the eighteenth century broke the ‘absolute citizen’ apart. The place of the citizen shifted from law to politics, from a legal subject to a political being. Absolute citizenship, created in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries by French jurists, was now being dismantled. Like Daniel Gordon, P. Sahlins insists on the republican discourse, but also on the more concrete political struggles for religious toleration and tax exemptions at the end of the Old Regime: ‘More than simply returning to the political citizen of Aristotle, republican Rome, or the medieval city-states of Italy, the eighteenth-century citizenship revolution involved, in this first instantiation, a fundamentally novel and essentially modern construction of the citizen as a public and political being distinct from the citizen as a legal member of the polity’.Ga naar voetnoot10 The good or true citizen was now conceived as a person devoted entirely to the public good; beyond this ethical behaviour, the citizen became the subject of certain rights, among them the right to the security of his person and of his property.

Peter Sahlins also highlights a second trend: on the one hand, as a rights-bearing member of society the citizen eventually became the very source of sovereignty; on the other hand, the category of citizenship became simultaneously more restrictive both socially and politically. The new citizenship passed from a legal membership category encompassing the totality of the French population to a limited membership category: only a portion of the population would be a citizen, and among them, even fewer could be ‘good citizens’. Generally excluded from the category were beggars, idlers, slaves, servants and, of course, women. In this lecture, I will leave aside all these exclusions, assuming all that has already been said in Marxist and feminist studies,Ga naar voetnoot11 but we need to keep in mind that the ‘citizen’ that I will mention now is | |

[pagina 11]

| |

a white male, who owns enough to be considered as ‘independent’ and potentially ‘autonomous’. Fair enough, but how accurate is this vision? Did the Enlightenment transform, so the story goes, ‘political status’ into ‘political agency’? In the second part of my paper, I will intentionally blur Sahlins' story, showing how an opposite trend was also at work in Montesquieu's masterpiece The Spirit of the Laws - before Rousseau's attempt, in the Social Contract, to subvert Montesquieu's categories (like Marx did a century later with Hegel's dialectic). I will not address here the classical topoi of the relationship between citizenship and nation building.Ga naar voetnoot12 Rather, I will go back to these major texts and reflect upon their attempt to build what I call a ‘realistic utopia’, taking men as they are and laws as they ought to be. | |

II. Two main contributions to the theory of citizenship: Montesquieu, Rousseau1) Montesquieu: from political agency to legal status?Is republican citizenship out of reach for modern times? In The Spirit of the Laws (1748), Montesquieu insists on the requirements associated with republican virtue. According to him, the survival of republican - and furthermore democratic - institutions can only be achieved through patriotic feelings (amour de la patrie), associated to love of equality (amour de l'égalité) and love of frugality (amour de la frugalité): ‘Love of equality in a democracy limits ambition to the single desire, the single happiness, if rendering greater services to one's homeland than other citizens’.Ga naar voetnoot13 Even more than to Aristotle's Politics, Montesquieu refers to Machiavelli's Discourses on the First Decade of Titus Livy. For Montesquieu, popular sovereignty is founded on civic, and not Christian virtue: political virtue is a preference for the public interest over the private interest. Civic practices associated to democratic citizenship therefore rely on equality and frugality, which must be maintained by agrarian and sumptuary laws. Private wealth and private pleasure must be banned from a democracy: the expansion of luxury and the escalation of private passions (such as ambition and greed) can only bring about corruption - the dissolution of patriotic feelings. Even more dangerous than the decline of the military virtues are the particularization of interests and the dissociation of the citizens' peculiar aspirations from the glory of their country (SL, VII, 2).

Civic virtue seems close to heroism. Citizens' participation in power demands the ‘continual sacrifice of our persons’ and of our interests,Ga naar voetnoot14 and the abandonment of a | |

[pagina 12]

| |

large part of the citizens' private lives and personal safety, all in the name of virtue. Maintaining equality alive is an ‘ever arduous’ task, requiring the perpetual constraint of customs (moeurs).Ga naar voetnoot15 Such a feat can only be achieved through a ceaseless moral policing, which would not suit at all modern monarchies, founded on honour and not virtue: ‘It is not only crimes that destroy virtue, but also negligence, mistakes, a certain slackness in the love of the homeland, dangerous examples, the seeds of corruption, that which does not run counter to the laws but eludes them, that which does not destroy them but weakens them: all these should be corrected by censors’ (SL, V, 19). In republican Rome, the institution of censorship was central; this unceasing supervision was supposed to lead to civic virtue. Montesquieu referred to the example of the Aeropagyte, where a child was put to death for having blinded his bird: ‘Notice that the question is not that of condemning a crime but of judging mores in a republic founded on mores’ (SL, V, 19). The instauration of a pyramidal chain of subordination also anchors political discipline in a moral bedrock. The subordination of the young to the old, of children to parents, of wives to husbands sustains the authority of the senate. In a democracy, this conservation of allegiance is paramount to the survival of the state (SL, V, 7). The corruption of the republic occurs precisely at the moment when public values lose their legitimacy in the face of a new emerging individualist order.  Charles-Louis de Montesquieu (1689-1755)

But is this conception of citizenship as political agency still within our reach? In the Spirit of the Laws, Montesquieu opposed ancient and modern times, virtue and commerce. A few exceptions set apart, Montesquieu regarded democracy as unsuited to modern states with large populations distracted from civic virtue by commerce, finance, and wealth. Thus he referred with a mixture of awe and admiration to ‘all the heroic virtues we find in the ancients and know only by hearsay’ (SL, III, 5). In his | |

[pagina 13]

| |

private notes (Mes Pensées), Montesquieu draws a line between Ancient and Moderns: Quand on pense à la petitesse de nos motifs, à la bassesse de nos moyens, à l'avarice avec laquelle nous cherchons de viles récompenses, à cette ambition si différente de l'amour de la gloire, on est étonné de la différence des spectacles, et il semble que, depuis que ces deux grands peuples ne sont plus, les hommes se sont raccourcis d'une coudée (Pensée 598). The development of commerce in contemporary European states condemns republics to corruption: ‘The political men of Greece who lived under popular government recognized no other force to sustain it than virtue. Those of today speak to us only of manufacturing, commerce, finance, wealth, and even luxury’ (SL, III, 3). Most of the time (Holland, Switzerland and other commercial republics were for a while exceptions to the rule),Ga naar voetnoot16 the development of commerce and wealth seems to be incompatible with the conservation of civic virtue. To Montesquieu, the ancient vision of citizenship is therefore obsolete. A lack of political virtue foredoomed the republican temptation in seventeenth-century England: It was a fine spectacle in the last century to see the impotent attempts of the English to establish democracy among themselves. As those who took part in public affairs had no virtue at all, as their ambition was excited by the success of the most audacious oneGa naar voetnoot17 and the spirit of one faction was repressed only by the spirit of another, the government was constantly changing; the people, stunned, sought democracy and found it nowhere. Finally, after much motion and many shocks and jolts, they had to come to rest on the very government that had been proscribed (SL, III, 3). So it may be said that the English Republican thinker Harrington, seeking liberty, ‘built Chalcedon with the shore of Byzantium before his eyes’ (XI, 6).Ga naar voetnoot18 The Spirit of the Laws thus painted a completely different picture of contemporary England as ‘a | |

[pagina 14]

| |

nation where the republic hides under the form of monarchy’.Ga naar voetnoot19 The ‘commercial society’ embodied a new modern direction in republicanism, which took on board the rapid rise of passions and interests.Ga naar voetnoot20 A new concept of citizenship was born: not the ancient citizen-soldier, nor the subject of the absolutist monarchy, but the vigilant working citizen. Politics, far from being forgotten by individuals absorbed by their private affairs, was still the main object of concern in England after the Glorious Revolution: This nation would love its liberty prodigiously because this liberty would be true; and it could happen that, in order to defend that liberty, the nation might sacrifice its goods, its ease, and its interests, and might burden itself with harsher taxes than even the most absolute prince would dare make his subjects bear. [...] Benjamin Constant would later follow Montesquieu on this line: in commercial societies, one finds the potential for a public spirit associated to rational self-interest; in the public sphere, the protection of private passions and interests depends on the full exercise of political rights. | |

2) Rousseau's theory of virtueApparently, Rousseau marked an even more dramatic break with the absolutist model of the citizen in his Social Contract. He was familiar with the Spirit of the Laws since his work as secretary of Madame Dupin, when he had to copy the masterpiece (the pages are kept today in the Library of Bordeaux). Later on, Rousseau accepted the main features of Montesquieu's depiction of republican citizenship, but refused to conclude that democratic citizenship was only one among other options. In his Chapter ‘Of Democracy’, in which he mentions that ‘taking the term in its strictest sense, no true democracy has ever existed, nor ever will exist’, Rousseau emphasized the extraordinary conditions that a democracy should meet (very small state, equality of rank and fortune). But from the same premises as Montesquieu he concluded the exact opposite: ‘That is why a celebrated author (Montesquieu) gave to the Republic virtue as its principle. For all these conditions could not subsist without virtue. But without having made the necessary distinctions, that fine genius often lacked aptness and sometimes clarity; he did not see that, Sovereign authority being everywhere the | |

[pagina 15]

| |

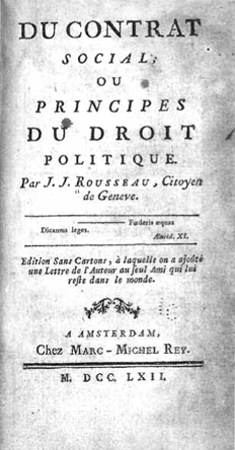

same, the same principle must apply in every well-constituted State, more or less to be sure depending on the form of Government’.Ga naar voetnoot21  Title page Du Contrat Social ou Principes du Droit Politique (1762)

What was wrong with Montesquieu? In his famous footnote of the Social Contract, Rousseau casts on all previous modern writers, except d'Alembert - whose article ‘Geneva’ he had already sharply criticized elsewhere: The true meaning of this word (citizen) has been almost wholly erased in the modern world; most people today take a town for a city and a townsman for a citizen. They are unaware that houses make a town but citizens make a City. [...] I have not read that the title Cives has ever been given to the subjects of any Prince, not even in Olden times to the Macedonians, not in our own day to the English, closer to liberty though they be than all the rest. The French alone adopt this title citizens quite casually, since as can be seen from their Dictionaries they have no real idea about it; otherwise by usurping it they would fall into the crime of Lèse-Majesté. Among them, this name expresses a quality, not a right. When Bodin thought to speak about our citizens and Townsmen, he made a serious blunder in taking one for another. M. d'Alembert did not fall into the same error, and in his article ‘Geneva’ clearly distinguished the four orders of men (even five, counting mere foreigners) who exist in our town, and of whom two alone make up the Republic. No other French author, to my knowledge, has understood the true meaning of the word citizen.Ga naar voetnoot22 The Social Contract dismissed all previous definitions of the citizen offered by philosophers, and singled out Bodin, noting that ‘when Bodin wanted to speak of our citizens and burgesses, he made the gross error of mistaking the one for the other’ (I, 6). But according to Peter Sahlins, the criticism was deeply unfair: ‘It reveals more about the prejudices of the self-proclaimed citizen of Geneva than about Rousseau as a close reader of texts. Bodin devoted great attention to the distinction between a bourgeois | |

[pagina 16]

| |

in a town or city and the citizen of the kingdom; the former was not a true but rather a merely “honorary” citizen’.Ga naar voetnoot23 Yet the footnote was meaningful: Rousseau dismissed Bodin and other French authors, among them Montesquieu, who ‘denatured’ citizenship by ignoring or minimizing its active participatory character.

To be a citizen, for Rousseau, is to act according to one's ‘general will’: to will the ‘common good’ of the body politic, rather than one's personal or particular interests. To act for the common good may require hard sacrifices. In his famous description of the lawgiver, Rousseau describes the requirements of membership: Anyone who dares undertake to give a people institutions must feel capable of so to speak changing human nature; of transforming every individual, who in himself is a perfect and solitary whole, into part of a greater whole from which this individual in a sense receives his life and his being; of substituting a partial and corporate (moral) existence for the physical and independent existence that we have all received from nature. [...] So that when every citizen is nothing and can do nothing other than through all his fellows [...], then legislation may be said to be at the highest point of perfection it can attain.Ga naar voetnoot24  Jean-Jacques Rousseau (1712-1778)

In Émile (and one may find similar texts in the Discourse on Political Economy, or in the Considerations on the government of Poland, Rousseau mentions the public education that was most powerfully depicted in Plato's Republic: ‘Good social institutions are those that best know how to denature man, to take his absolute existence from him in | |

[pagina 17]

| |

order to give him a relative one and transport the I into the common unity, with the result that each individual believes himself no longer one but part of the unity and no longer feels except within the whole. A citizen of Rome was neither Caius nor Lucius, he was Roman’.Ga naar voetnoot25

But this view is not uncontroversial. Recently, the political theorist Joshua Cohen considered that this line of interpretation got Rousseau wrong, or focused on Rousseau's own exaggeration. According to J. Cohen, ‘Rousseau does not embrace the strong conception of civic unity that we find in Plato's Republic’.Ga naar voetnoot26 He does not subscribe to the Platonic conception where citizens identify their own good with the good of the whole. Contrary to a widely accepted interpretation, Rousseau does not endorse a vision of the citizen whose individual interest and identity are fully absorbed into a public identity. Membership in the society of the general will does not require the complete renunciation of all particular desires. Rousseau was well aware of the difference between ancient and modern peoples. Talking to Genevans, he treated them as ‘bourgeois’ rather than true citizens: ‘you are neither Romans, nor Spartans; you are not even Athenians. Leave aside these great names that do not suit you. You are Merchants, Artisans, Bourgeois, always occupied with their private interests, with their work, with their trafficking, with their gain, people for whom even liberty is only a means for acquiring without obstacle and for possessing in safety’.Ga naar voetnoot27

J. Cohen, however, does not conclude from this well-known page that citizenship is out of reach for modern individuals according to Rousseau. He insists on the difference between citizenship as an absorption in an organic whole (a negation of the self), and citizenship as the ability to make sound deliberations and decisions. The great-legislator passage about the pitch of civic perfection also conflicts with what Rousseau says elsewhere about the persistence of separate interests and a dimension of private personhood in the society of the general will. Citizens cannot fully transcend the conflicts between inclination and duty, and fortunately, a just society does not require a renunciation of all particular interests. Finally, the real issue with civic virtue is primacy. According to this ‘liberal’ interpretation, one of Rousseau's chief concerns is to figure out what takes precedence in practical reason, in our deliberations about appropriate public conduct. We all want to be secure and free, but perhaps prefer that others bear the costs; so there is always a danger that, as Rousseau writes, ‘in detaching his own interest from the common interest, each sees clearly that he cannot separate it off entirely; but his share of the public evil seems as nothing to him, compared with the exclusive good that he means to appropriate. This particular good | |

[pagina 18]

| |

aside, he wills the general good in his own interest just as strongly as anyone else’.Ga naar voetnoot28

Finally, citizenship is associated here to the duty of fair play, or to the ‘sense of justice’: one should not benefit from just institutions and avoid bearing the burden or paying one's fair share. J. Cohen's ‘light version’ of Rousseau's theory of citizenship is typical of its appropriation by liberal contemporary theorists, who do not wish to defend an archaic view of political virtue. Opposed to the republican rehabilitation of Rousseau (Maurizio Viroli, Jean-Fabien Spitz), this ‘liberal’ reading of Rousseau must be kept in mind; it allows for a contemporary reassessment of his conception of citizenship. In a nutshell, the citizen is just a name for the responsible, intelligent individual, aware of his fundamental interests, who consequently does not want to be a free rider of just institutions. | |

III. John Rawls' realistic utopia John Rawls (1921-2002)

So what is left of the Enlightenment's theory of citizenship? As a precursor of the Kantian concept of autonomy, Rousseau may be considered as a central inspiration for one of the most important political philosophers of the twentieth century, namely John RawlsGa naar voetnoot29 (who taught Joshua Cohen at Harvard).Ga naar voetnoot30 In his stated wish to round off the tradition of Locke, Rousseau and Kant, Rawls cites The Social Contract as one of the sources for his theory of ‘well-ordered society’, arguing that it opened the way for him to combine a contract-based theory of justice with a reflection on the ‘stability’ of a just society.Ga naar voetnoot31 In A Theory of Justice, Rousseau's contractualism is instrumental in clarifying how the concept of equality is bound up with that of liberty; it accounts for the formation of the motives that will enable institutions to survive in the long term. Rawls partly situates in Émile the origins of his own theory of the ‘sense of justice’ which enables reasonable agents to understand and follow principles of justice, and to follow their duty of fair play.Ga naar voetnoot32 Thus, far from being a | |

[pagina 19]

| |

source of totalitarianism or a gravedigger of liberty, and unlike the way a certain Cold War liberal tradition would depict him,Ga naar voetnoot33 Rousseau appears as the advocate of a just and stable society, conceived as the essential prerequisite for true freedom. For the first time in history, he appears as a forerunner of political liberalism.Ga naar voetnoot34 But one needs to be clear as to which Rousseau is an ally in Rawls' critique of utilitarianism. In the last part of my lecture, I shall therefore focus on the reading outlined in Rawls' Lectures on the History of Political Philosophy, given to Harvard graduates and undergraduates between the second half of the 1960s and the second half of the 1990s.Ga naar voetnoot35 In these synoptic courses covering the period from Hobbes to Marx (taking in Locke, Hume and Mill and a few variants),Ga naar voetnoot36 Rawls ventures a bold interpretation of Rousseau's theory of citizenship in terms of ‘realistic utopianism’. | |

1) The sense of justiceIn his Lectures, Rawls translates Rousseau's idea in his own terms: to be a citizen is to pursue one's ‘fundamental interests’ (mainly freedom, equality and the development of our faculties). To Rawls, it is clear that this modern theory of citizenship appears with Rousseau: in contrast with Hobbes and Hume, Rousseau does not identify the citizen's fundamental interests with the drive for self-preservation and acquisition, nor does he identify them with ‘property’ (goods, life and liberty), in contrast to Locke. According to Rousseau, both amour de soi and amour-propre can find their optimal expression in society, not in the sense that individuals can maximize their well-being when they live within society, but rather in the sense that freedom, perfectibility and the egalitarian desire for recognition can all develop within it.Ga naar voetnoot37 Thus, in his Lectures, Rawls regards Rousseau as one of the most important thinkers on the issue of citizenship while claiming a liberal understanding of his theory. All that is required for the stability of society is a ‘sense of justice’, which is a capacity to understand and to follow the principles of justice based on the social contract.Ga naar voetnoot38 Rousseau's definition of autonomy, as obedience to the law that one has laid down oneself, is at the heart of citizenship. Citizenship in society allows a passage from instinct to morality and makes human beings capable of obeying the very laws that they institute for themselves.Ga naar voetnoot39 | |

[pagina 20]

| |

Not only does the social contract provide the essential social background conditions for civil freedom (‘assuming that fundamental laws are properly based on what is required for the common good, citizens are free to pursue their aims within the limits laid down by the general will’)Ga naar voetnoot40; it accounts for our moral freedom, since the general will is our own will, our true will.

In this powerful line of interpretation, Rawls implicitly discusses Judith Shklar's influential reading in Men and Citizen. For Shklar, the citizen's general will pursues ‘nothing but a hard personal interest’, even if it is an interest that all citizens share. Nor is its content vague: it always tends to equality. In other words, the general will ‘is general because the prevention of inequality is the greatest single interest that men in society share, whatever other ends they might have’.Ga naar voetnoot41 The citizen pursues the interest of man in general against those particular wills, which lead men to seek privileges. Finally, the general will is the will of ‘man in general’, a will to fairness towards all.Ga naar voetnoot42

Yet Rawls brings back into the picture the political dimension of citizenship: the general will is based upon deliberation among individuals, conducted under conditions of fairness (SC, II: 4). For sure, the general will is understood as abstracted from any particular determination or interest; that is why the general will wills justice. In his Lectures, Rawls quotes Rousseau: ‘[T]he idea of justice, which the general will produces, derives from a predilection we each have for ourselves, and thus derives from human nature as such’.Ga naar voetnoot43 As in Shklar, citizens will equality first, because of the nature of their fundamental interests, including their interest in avoiding the social conditions of personal dependence (equality is necessary for liberty). But pace Shklar, citizenship cannot be conceived without an institutional background: ‘[O]nly reasons based on the fundamental interests we share as citizens should count as reasons when we are acting as members of the Assembly in enacting constitutional norms or basic laws’.Ga naar voetnoot44 That is what citizenship is truly about: the fundamental interests take absolute priority over our particular interests when we vote for fundamental laws and consider basic political and social institutions. A little later, the Lectures define the general will from the point of view of ‘public reason’. To vote in accordance with the general will means to accept as valid only a certain kind of reasoning in public deliberation, the | |

[pagina 21]

| |

kind that corresponds to Rawls' own conception of public reason.Ga naar voetnoot45 Building on these premises, the fact that the general will is always straight, constant, unalterable and pure does not make it either a transcendent idea or a dictate of the sovereign power: the general will is conceived as a form of deliberative reason exercised by each citizen; it is what remains after we take away the particular interests which incline us to partiality.Ga naar voetnoot46 | |

2) The social spiritYet it might be objected that Rousseau's theory of citizenship in the Social Contract provides evidence of his authoritarian, or even totalitarian, tendencies. Rousseau's influence on Robespierre and many other Jacobine actors of the French Revolution has often been interpreted in that light. In order to foster patriotism, the lawgiver is supposed to provide the citizen with a form of ‘social spirit’ (esprit social). This social spirit is meant to inform the citizen's desires and beliefs, so that he always gives preference to the common good over his private interests. This has deep implications for the theory of the lawgiver, especially at the founding moment. But for Rawls, the legislator who dares to set about constituting a people of citizens is by no means a demiurge creating a ‘new man’ from scratch. The lawgiver makes it possible to express the social nature of human beings, and brings them to recognize the fundamental interests they have in common. Citing the controversial section of The Social Contract on the need to transform human nature so that a man can become a citizen (II: 7), Rawls debunks the liberal ‘anti-totalitarian’ interpretation.Ga naar voetnoot47 The wish to shape human beings in conformity with the goals of society appears sound, since there is really a need to face the critical issue of stability in the just society, and therefore to shape a social spirit. Rawls thus overturns the anti-totalitarian reading of Rousseau, which condemned him for wanting ‘to force men to be free’.Ga naar voetnoot48 In Rawls' view, once this phrase is placed in context, it gives no cause at all for indignation. On the contrary, it amounts to a common-sense notion that lies at the heart of a properly conceived theory of citizenship: if laws lacked the coercive power to command obedience, some people would be able to operate in society as ‘free riders’, enjoying its benefits without making any contribution of their own. The point is that, if people could enjoy their rights without fulfilling their duties, this would undermine the conditions for mutually advantageous cooperation and thereby compromise the liberty of all. Moreover, to force a recalcitrant citizen to discharge public obligations while enjoying social benefits is | |

[pagina 22]

| |

in effect to make him free, where what is at issue is a moral freedom that goes beyond satisfaction of the instincts and reaches true self-mastery. Citizens are as free after the contract as they were before it (albeit in radically different ways): to force citizens to be free is to remove them from relations of domination and subordination and to place them in relations of mutual respect.Ga naar voetnoot49

Finally, Rawls is aware that this conception of citizenship relies on certain material conditions. Since social inequalities give rise to dependence, fuelling arrogance and scorn on one side, and servility and deference on the other, they must be fought in so far as they do not strictly contribute to public utility. On this point, Rousseau argued that social and economic inequalities should be limited, to ensure the conditions under which citizens can be independent and the general will can achieve adequate expression: ‘does it follow that it [inequality] must not at least be regulated? It is precisely because the force of things always tends to destroy equality that the force of legislation ought always to tend to maintain it’.Ga naar voetnoot50 Rawls takes this remark as inspiration for his reasoning why the basic structure of society (its social institutions) is the primary subject of justice. The limitation of inequality is required to ensure the conditions for liberty, but also the conditions for the highest level of equal respect. It is thanks to limits on social and economic inequality that citizens think of themselves as really equal; they are endowed with the same fundamental interests in ensuring liberty and pursuing their goals within the limits of the law, and with the same capacity for moral freedom. According to Rawls, Rousseau's true originality is most apparent in this social dimension of his doctrine, which draws out the necessity of an equal respect to which material equality is supposed to be instrumental.Ga naar voetnoot51

Hence, despite all the criticism which arose after the Terror and, again and again, after the fall of totalitarian regimes,Ga naar voetnoot52 Rousseau remains a guide for many modern theories of citizenship. There is a risk, however, that in trying to paint Rousseau as a modern liberal one might distort his thought. To take men as they are means to take into account their desires and beliefs, which cannot be reduced to their higher-order interests. In his Constitutional Project for Corsica and in his Considerations on the Government of Poland (two works Rawls never mentions), Rousseau suggests institutional and moral devices to reshape human passions in order to produce citizenship and virtue. To be sure, love of country is the end citizens should pursue; sometimes associated to ‘civil religion’, it can never be reduced to any ‘reasonable’ and ‘rational’ interest. In the Social Contract itself, where the word ‘virtue’ is almost absent, citizens are not only motivated by their desire for freedom and perfectibility. In a well-ordered society, | |

[pagina 23]

| |

the main object of desire becomes the motherland - an expansion of amour de soi to encompass the enlarged self of the country. The emphasis is put on a national solidarity, an attachment to a distinctive way of life, and on demanding requirements of civic virtue.Ga naar voetnoot53

So, Rawls can further his ends only by painting Rousseau with a particular, partly deformed face in order to make him an ally against the utilitarian mainstream. The citizen here becomes an alternative to the free rider. His sense of justice is supposed to make him act according to the duty of fair play, and to sustain just institutions from which he has benefited. It is a Rousseau without passions, a Rousseau without tensions, who lays bare the depravities of society in order to offer a more rational path to a ‘realistic utopia’.Ga naar voetnoot54 |

|