Burgerhartlezing 2012. Nobody's Children? Enlightenment Foundlings, Identity and Individual Rights

(2012)–Catriona Seth, [tijdschrift] Burgerhartlezing, [tijdschrift] Documentatieblad werkgroep Achttiende eeuw–

[pagina 7]

| |

Nobody's Children?

| |

Identity on the cardsIn 1770, it is estimated that 35% of children born in Paris were abandoned.Ga naar eindnoot1 The figure had risen steadily over the century. The great scientist d'Alembert owed his Christian names - Jean le Rond - to the fact that he was left on the steps of the church of Saint-Jean le Rond in Paris, near Notre-Dame cathedral, in 1717, as his unmarried mother, Claudine-Alexandrine Guérin de Tencin, daughter of a renowned noble family and a famous intellectual in her own right, had no intention of bringing him up. He was one of the luckier ones: his father's family paid a pension to his nursemaid and he was given a loving foster home. But the most famous foundlings perhaps of the whole of the eighteenth century have disappeared from view. They are the five children Rousseau claimed to have had with his semi-illiterate partner Thérèse Levasseur. Voltaire revealed their existence to the public at large in a pamphlet called Le Sentiment des citoyens (1764). This poured scorn on the author of the period's most famous pedagogical treatise, Emile (1762), who had cast out his own offspring. Rousseau himself admitted to having abandoned his children both in texts like his autobiographical Confessions and Rêveries du promeneur solitaire, and in private correspondence, for instance in a 1751 letter to Suzanne Dupin de Francueil,Ga naar eindnoot2 the daughter of one of his patronesses. He who was to be a metaphorical father-figure in many upbringings and the very ‘père de la Révolution’ according to republican doxa, severed all links with these children, whose precise dates of birth are unknown. In the first reference to his paternity in the Confessions, Rousseau states he heard | |

[pagina 8]

| |

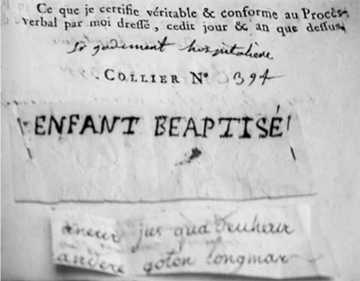

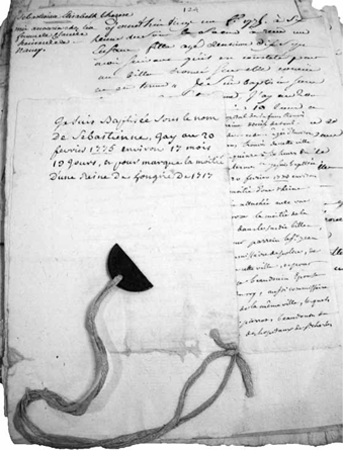

frequent mention of the foundling hospital in Paris within a circle of people of sometimes dubious moral standing who frequented Mme La Selle. He started to believe that abandoning children was not necessarily to be rejected if you were an honest person in any kind of trouble, a seduced woman, a cuckolded husband, a partner in an illicit affair and so onGa naar eindnoot3 - as a character in an earlier novel, himself a foundling, put it: Qu'ils soient bâtards ou légitimes, on ne s'informe jamais d'où ils [the foundlings] viennent. Grande ressource pour les pauvres! Mais commodité bien plus grande pour cacher les fruits impurs d'un amour clandestin!Ga naar eindnoot4 Madame Levasseur helped Rousseau convince Thérèse that the foundling hospital would be the best place for her future child: [...] On choisit une sage-femme prudente et sûre, appelée Mlle Gouin, qui demeurait à la pointe St-Eustache, pour lui confier ce dépôt, et quand le temps fut venu, Thérèse fut menée par sa mère chez la Gouin pour y faire ses couches. J'allai l'y voir plusieurs fois, et je lui portai un chiffre que j'avais fait à double sur deux cartes, dont une fut mise dans les langes de l'enfant, et il fut déposé par la sage-femme au bureau des Enfants-Trouvés, dans la forme ordinaire. L'année suivante, même inconvénient, au chiffre près qui fut négligé.Ga naar eindnoot5 Rousseau abandoned his first child, probably born in 1746 or 1747, with a cipher - what Shakespeare calls a ‘character’ in The Winter's TaleGa naar eindnoot6 - on a playing card. One could speculate about the aspects of chance which card-games entail, and indeed about the card itself - did Rousseau choose a King of Hearts, for instance, or his favourite number? One should however also keep in mind that the back of playing cards was blank at the time and that they were often used for taking notes - Louis XVI jotted down lists of people to invite and Rousseau himself penned drafts for the Rêveries du promeneur solitaire on cards. They were also, as the case of Rousseau's infant suggests, often used to identify foundlings, usually because the object itself was personalised with a note. The Jack of Clubs on the back of which baby Sophie's details were written on September 13th 1783 in Rouen, gives an example of the practice. The pale blue ribbon attached to the card was used to tie it to the girl's neck.Ga naar eindnoot7 The coloured card would be immediately identifiable, even to one who could not read - as the childhood game of ‘snap’ shows even nowadays. The message on the reverse gave important details concerning the infant, but not her parents' names. Foundling hospitals in France accepted anonymous children: the parents did not need to identify themselves. Many towns had foundling wheels in which an infant could be left without the person who had brought him or her being seen from within the hospital or convent in which they were situated. Anonymity was preserved in ex- | |

[pagina 9]

| |

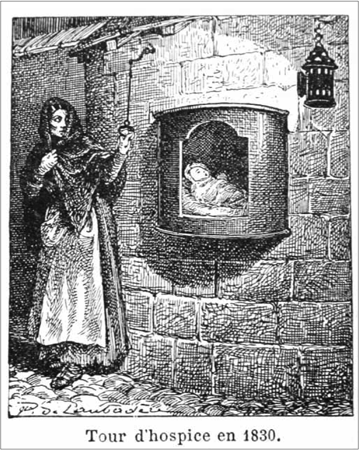

actly the same way as with modern ‘baby-boxes’ which have sprung up in countries like Belgium, Germany and Japan - the two installed in Hamburg in 2000 were set up with specific reference to foundling wheels, which were put into service in the Hanseatic town between 1709 and 1714 at the instigation of a Dutch tradesman.Ga naar eindnoot8   Figures 1 and 2: Playing card left with a foundling in Rouen on September 13th 1783

| |

Reading (between) the linesFor the child to be given an identity in eighteenth-century foundling hospitals there was a two-way process. In the first instance, the parent, like Jean-Jacques Rousseau, could leave a note affording elements of information. It might be a fully-blown official document, like a baptismal certificate complete with the full names of the birth mother and father, or it could be something allusive like a cipher or a quotation, a request (for the child to be given a particular name, for instance, or to be brought up without swaddling), prayers, thanks etc. It sometimes offered some kind of explanation for what could be construed as a desperate gesture - Rousseau in his aforementioned letter to Mme de Francueil states why he left his children: J'ai mis mes enfants aux Enfants-Trouvés; j'ai chargé de leur entretien l'établissement fait pour cela. Si ma misère et mes maux m'ôtent le pouvoir de remplir un soin si cher, c'est un malheur dont il faut me plaindre, et non un crime à me reprocher. Je leur dois la subsistance, je la leur ai procurée meilleure ou plus sûre au moins que je n'aurais pu la leur donner moi-même.Ga naar eindnoot9 | |

[pagina 10]

| |

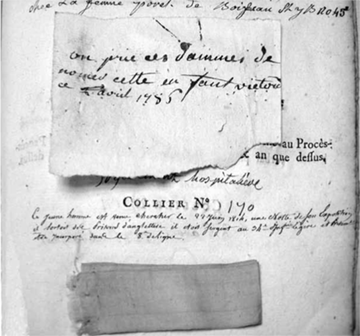

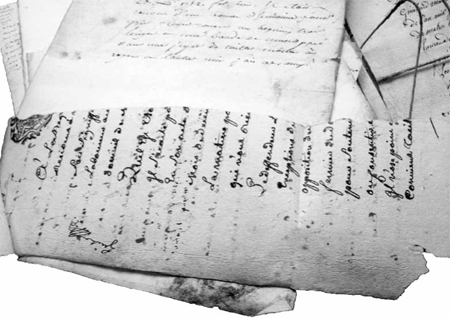

Unlike some of his contemporaries who could not envisage having another mouth to feed, Rousseau was not dying of hunger, but he had no regular income and never knew what the morrow would bring. His contention that, ‘par la rustique éducation qu'on leur donne, ils [his abandoned children] seront plus heureux que leur père’, was considered a form of sophistry by contemporaries like the marquise de La Tour du Pin,Ga naar eindnoot10 but echoes other comments of the time as one discovers in the records kept in various archival sources. In January 1789, little Lucien was found in Rouen with the following note which may well have been dictated by parents who could neither read nor write as they are referred to in the 3rd person and it uses both the pronouns of the 1st and 3rd person singular to refer to the infant: je suis né aujourd'hui 7 janvier de légitime mariage. Mon père et ma mère souffrant d'extrême misère ont été hors de pouvoir de luy faire recevoir le Baptême et de me rendre les services que ma tendre jeunesse les oblige de me donner. Ce n'est qu'avec la plus humiliante affliction et douleur la plus sensible qu'il m'abandonne et m'expose en attendans que le ciel les favorise destre en état de me rappeler au sein de ma famille.Ga naar eindnoot11 When infants - etymologically those who cannot talk - are purportedly, as in the lines I have just quoted, the authors of messages, this may be because they are deemed to be innocent and therefore seen as more susceptible to be welcomed by the authorities than their parents who have failed them. It may also be that they are being released, empowered, and emancipated de facto: nobody else can speak for them as their parents have renounced any responsibility for their offspring.  Figure 3: Illegible note left with an 18th-century foundling in Lorraine

| |

[pagina 11]

| |

Figure 4: Message left with an 18th-century foundling in Normandy

Such texts were not merely a way for the abandoning parent to make him or herself feel better and, implicitly, to implore the benevolence of any civil or religious authorities who might judge them ill for abandoning their child, but they were a way to identify the foundling. There was an implicit trust, even by the illiterate, in the written word as a means of identifying a child or indeed, beyond strings of letters or sometimes numbers, in any sign scratched, with pen and ink, on a scrap of paper - sometimes a recuperated piece which has another text written or printed on the reverse side.Ga naar eindnoot12 Occasionally it is impossible to decipher a message, as the nuns indicate in their registers - see the apparent set of names which make no sense, ‘viacques guiller our mes’ -, or to understand the meaning of the letters painstakingly inscribed by someone whose mastery of the written language was shaky at best as in the ‘O O O’ on the scrap of paper appended to a foundling register in Rouen. Many of the children were left with notes written either by the person who was present at the birth, a midwife or surgeon, in the case of a new-born - and most foundlings were new-borns - or by a scrivener. To give a precise figure as an example, in Rouen, between November 4th 1776 and October 20th 1777, 255 of the 375 children received by the hospital bore a written message - this means that more than 2/3 of the foundlings had notes at a time when literacy rates were not that high.Ga naar eindnoot13 Take the case of a 9-month-old boy whose mother gave an unusual number of details in her note: L'enfant est Baptise ils apelle Pierre Louïs La mere est incapable de le nourrir elle prie les Dames de prester leurs soins de charité pour Le petit garçon on Le Retirera dans 18 mois au plus Tart deux ans La marque de Teste est un rubant gris blanc Trois neux un Rubant aux col et aux bras gaushe fait a Roüen Ce 14 9bre 1775. Cet | |

[pagina 12]

| |

Enfant a 9 mois 8 jours on prie Ces Dames Den avoir soin Car il est Extremement vif. fils naturel de marie francoise Léchalier.Ga naar eindnoot14 The mother returned to pick up her child almost immediately. She was asked to sign for him but just drew a cross, as she was illiterate. An administrator noted that the mark was that of Marie Françoise Lechalé, femme Caron.Ga naar eindnoot15 She was married yet if we return to church registers, we discover further details regarding her son. He was christened in the working-class parish of St Maclou in February 1774. His mother's name is given as Marie Françoise Lechelier but his father is said to be unknown. His godfather, who painstakingly wrote his name on the parish register, is a sawyer called Pierre Caron. The plot thickens with a godfather whose surname is the same as that of Pierre Louis' future stepfather... Three months after his initial brief passage, Pierre Louis was back at the hospital with a new note: Jay Exposé mon Enfant Le 21 fevrier 1776 cet Enfant senomme pierre Louïs agé dun an et 14 jours il a pour vêtement une Brassiere a Tour bleu, un petit bonet de plusieurs Couleurs qui sont blanche rouge et vertes, un Mauvais Lange, il a pour Remarque un petit bout de CordeLet blanc au Col nouë a deux noëuds ainsy qu'au bras gauche on Redemandera LEnfant dans 3 ans aux plus Tard on vous prié d'en avoir soin Le Dit Enfant est fils naturel de Marie francoise Lechaley.Ga naar eindnoot16  Figure 5: Note stating a child has been baptised but which does not give a name (Rouen, 1784)

On both occasions, the boy's age is given with the utmost precision, which is, in itself, an indication of his importance to his mother. She disclosed her full name and admitted to the child's illegitimacy. The second time she left him, she promised to take her son back within three years. She was true to her word: on December 14th, a little less than 10 months later, she picked him up again. The boy was in and out of the home, | |

[pagina 13]

| |

which shows that occasional stints in the institution were ways of making ends meet for people with limited means: Marie Françoise Léchelier never intended to get rid of her child; she wanted him back. When she made promises, she kept her word. The boy was initially registered with the number 655. On his second stay in the hospital he became number 768. Nothing in the archives suggests that anyone made the immediate connection between his first and second visit, even though he was one of the rare foundlings not to be a new-born and to have been deposited, on both occasions, with a note which gave his full identity - if one excepts the problematic question of who his father was and whether his godfather and stepfather were one and the same. | |

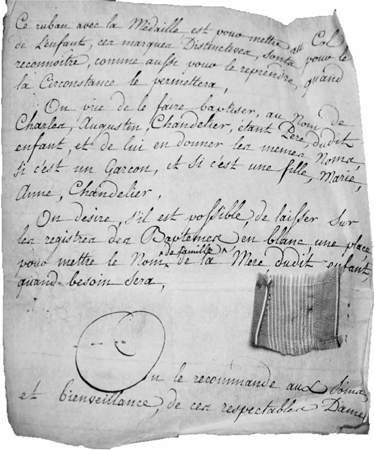

Christian names or forenames?The notes left with foundlings, known in French as ‘excuses’, afford different types of information. Sometimes there is a single word: ‘Baptisé’, which acts as a sort of letter of introduction in order to let everyone know the child is their brother or sister in Christ and will not go to limbo if he or she diesGa naar eindnoot17 - at a time when infant mortality was so high in such institutions that Panckouke's Dictionnaire des Sciences Médicales suggested that they should have, engraved over their doors, an inscription reading: ‘Ici on fait mourir les enfans aux frais du public’Ga naar eindnoot18 [Here children are allowed to die at public expense]. The Christian name is not necessarily noted as though it was unimportant compared with the fact of having been welcomed into the Church and having thus become one of God's children, like in the 1784 note on the photograph. Such is also the case in the 1785 note where capitals give the essential information: ‘ENFANT BEAPTISÉ’.  Figure 6: Note simply stating an abandoned infant has been baptised (Rouen, 1785)

Some foundlings were left with their baptismal certificates. Failure to deposit such a document with a christened child may denote a desire to hide his or her parentage: one did not always admit the same information to all. Your parish priest would know you. When I first became interested in Enlightenment attitudes towards foundlings, I hunted for the baptismal certificates of children abandoned in Rouen. I fast came to know which of the more than 20 parishes of the city were the ones in which poor mothers were most likely to give birth. When they left their children with even minor indicati- | |

[pagina 14]

| |

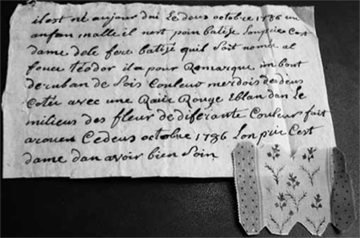

ons, such as a Christian name, I sifted through the parish registers to try to ascertain whether there were further clues as to their identity and background. At times I discovered that a mother might hide her name from the foundling hospital, but give it in full to the priest, as though afraid of not admitting to her true identity when meeting with God's representative on earth. Possibly ashamed by your action - as the fact that most children were abandoned before dawn or after dusk tends to show - you might not feel like letting on to the foundling hospital who you were and where you came from.  Figure 7: Note and ribbon left on October 2nd 1786 with an infant in Rouen

At other times, the message gives a name but adds that the child has not been christened, as in the following case: the picture shows the scrap of exquisitely printed flowery ribbon, which was included for identification purposes, and one can notice that it has been cut out to add further detail. It has obviously been chosen because it is highly original and thus easy to recognise. As it is a luxury item, there is no waste - only a small piece, just sufficient to work out the repeat in the pattern, has actually been left: il est né aujour dui Le deus octobre 1786 un anfan malle il nest poin batise. Lonprie Cest dame dele fere batisé quil Soit nomér al fonce téodor il a pour Remarque imbout de ruban de Sois Couleur merdois des deus Cotés avec une Raiie Rouge Eblan dan Le milieus des fleur de diferante Couleur fait arouen Cedeus octobre 1786 Lon prie Cest dame dan avoir bien Soin.Ga naar eindnoot19 Or the following: Une fille nommée Marie Louise Godefroy née le 28 8bre 1771, portant pour reconnaissance un petit morceau de ruban de soie à fond blanc peint de plusieurs couleurs sur lesquelles est imprimé un cachet dont on garde le double afin d'en user le plus tôt possible pour rendre ladite fille à des parents que des raisons de nécessité forcent d'agir ainsi pour le moment. On recommande à l'humanité cette enfant que l'on prie de ne point éloigner. Dès les premiers moments que l'on saura où elle est, l'on gratifiera la nourrice par les mains des dames de l'hôpital chargées de ce | |

[pagina 15]

| |

soin si la chose est favorable comme on se l'imagine. Elle n'a reçu nulle forme de baptême.Ga naar eindnoot20 Such cases occur more often as we approach the end of the century, which tends to confirm that religion was, to a certain extent, losing some of its influence.Ga naar eindnoot21 It also points to the importance of individual identity illustrated by one's own name as opposed to the collective salvation offered by the Christian church.  Figure 8: 1785 note requesting an infant be called Victoire

In a note like Marie Louise Godefroy's she has a clear identity with what would appear to be two Christian names and a surname. She exists as an individual even though the Church act of baptism, which was the only source of records - and therefore of official identity in Ancien Régime France -, has not taken place. This is all the more interesting in that some foundling hospitals - though not Rouen where she was abandoned - would change any given names as a matter of course.Ga naar eindnoot22 This shows a definite secularisation of identity, which is being tied to the birth parents' choice and not to the act of welcoming the new-born into the church with his or her godparents as patrons of the symbolic birth, as their name indicates. Many parents stressed how important it was to them for their child to bear a particular name. The playing card pictured supra left with a little girl who had been christened ‘Sophie’ illustrates this. The message ends: ‘qui [i.e. qu'il] ne me soit pas donné d'autre Nom’ [I am not to be given any other Name]. We have no indication as to why it was selected, but there | |

[pagina 16]

| |

was probably a reason for it to have been chosen, above and beyond the fact that it was pretty or fashionable - it was the name of one of the royal princesses. It may have been the name of the baby's mother or of another member of her family or entourage and it could therefore have an implicit protective value, as though by calling the girl Sophie one could guarantee her the talents, looks or charm of another person of that name. To give another slightly different example, it is unlikely that the child left in 1785 with a pink ribbon and a request for her to be named Victoire - another of the royal princesses bore that particular name - had been christened since there is no remark to that effect. It is also a name whose meaning is immediately obvious in modern French.  Figure 9: Note giving alternative Christian names according to the child's sex

| |

[pagina 17]

| |

The parents' own Christian names are requested for their child in a message, which had been drafted before the future foundling was actually born. This is clear as two options are set out with the alternative of the baby being baptised - by the hospital - as Charles Augustin Chandelier, after his father, if he is a boy, or as Marie Anne Chandelier if she is a girl. The sisters are also asked for the baptismal register to include a blank space in which the mother's maiden name can be inserted at a later stage. This suggests that the mother is being protected, either because she is unmarried or because she is married to someone other than Chandelier, but also that the new-born infant is to be given a partial identity at birth - that of its father -, and a full identity as soon as the mother can reveal her name without fear of reprisals or shame. Written in an elegant hand, on a large sheet of paper, the message was probably dictated - possibly to a scrivener - as its composition prior to the actual birth suggests. It would tend to indicate that baby Chandelier's mother, at least, was illiterate. At times there may have been, in Catholic France, a desire to put the child under the patronage of a particular saint, and this can have led to the choice of a name. It is clear that in cases like this the parent was not forfeiting all right to the infant. Stressing the importance of names, the Enlightenment writer Bernardin de Saint-Pierre noted that ‘Un enfant se patronne sur son nom’, quoting Bayle's example of the unfortunate sound of the inquisitor Torquemada's surname and its links to burning.Ga naar eindnoot23 As Saint-Pierre mentions, a name can help forge one's character: Notre nom est le premier et le dernier bien qui soit à notre disposition; il détermine, dès l'enfance, nos inclinations; il nous occupe pendant la vie et jusqu'après la mort. Il me reste un nom, dit-on. Ce sont les noms qui illustrent ou déshonorent la terre.Ga naar eindnoot24 By giving a name, a parent was offering an intangible, immaterial gift, one whose full meaning could not be understood without explanation - all of us at some time or another have wondered why our names were chosen for us: after a relative? a famous person? a place? One of my French friends always thought she had been named ‘Joséphine’ after her grandmother's cook until she discovered that her mother had a particular devotion to St Joseph. In addition, whilst one could be abandoned with warm clothes, these would do their time. One can never outgrow one's name. This suggests that some children were left because materially it was impossible to keep them, but also that on an affective and symbolic level, their parents did not wish to cut all ties with them. The choice of a name was like a blessing given. A child would have more reality if thought of as Jean or Madeleine, than simply as an anonymous baby one had abandoned: in the choice of name, there is an individualisation de facto. There is also an implicit idea that the child will live and need a social identity, not simply a safe-conduct to Heaven. | |

[pagina 18]

| |

Meeting the foundlings halfway Figure 10: Half coin left in 1775 with a foundling from Lorraine

Rousseau states, as we have noted, that, on abandoning his first child, he left a playing-card with a cipher and kept a copy. The fact of writing the message out twice or writing it out once and cutting it in two in order for the matching parts to be shown or to come together is at once an indication of a characteristic process of the time, as surviving archives show, and a gesture with huge symbolic impact. The most obvious illustration of this is probably to be found when children are left, not simply with a token like a cross or an engraving of a local saint, but with halves of coins, pictures or ribbons: obviously by reuniting the two halves, the one left with the foundling and the one brought by the parent, one would have an external confirmation of identity. No-one outside the abandoning process would know enough to create a fake in order to recuperate a child and the parent could go back secure in the knowledge that by bringing one half and being given the foundling left with the other half, he or she was returning with his or her offspring. The picture shows Sebastienne Gay's token, left with her in 1775 when she entered the Nancy foundling hospital. It is a simple coin. | |

[pagina 19]

| |

At other times children were left with halves of rare foreign currency or of medals. Fictional tales and plays often use similar objects as ways to identify characters. In the 1718 Promenades de Mr Le Noble, an illegitimate child of two high-ranking parents is christened under false names and left at the foundling hospital with fine linen, a purse containing the princely sum of three hundred louis and half an antique gold coin wrapped in a note reading: ‘On prie que cet enfant soit élevé avec distinction, il sera retiré par celui qui apportera la contrepart de cette pièce’.Ga naar eindnoot25 In a novel written just after the Revolution by Ducray-Duminil, a little girl called Jeanne, known as Jeannette, is adopted from the Paris foundling hospital by Monsieur and Madame d'Eranville, a noble couple with no family of their own. She is well treated by them, clothed in fine garments, calls them ‘Maman’ and ‘Papa’, but falls short of being treated like a legitimate child, especially when Mme d'Eranville gives birth to a daughter: ‘Tout était changé pour Jeannette: elle sentait qu'elle n'était plus qu'une pauvre fille des Enfants-Trouvés, élevée par charité, et qui devait, par ses services, reconnaître les bontés qu'on avait pour elle.’Ga naar eindnoot26 She is in a sense returned to the identity of a foundling, with no particular prospects, and her adoptive parents intend to marry her off to a farmer. Her prospects change after the dying Monsieur d'Eranville reveals a surprising document - the piece of paper discovered when she was found: Ma femme et moi nous avons enfermé soigneusement cet écrit, assez vague d'ailleurs, et nous n'avons jamais voulu en faire usage; mais, si tu en as besoin, Jeannette, tu t'en serviras [...]. Jeannette, si tu m'en crois, tu resteras dans l'ignorance où tu as vécu jusqu'à présent. À quoi te servira-t-il de retrouver des parents qui ont été assez dénaturés pour t'abandonner, qui peuvent à présent abuser de leurs droits imaginaires pour te tourmenter? S'ils sont pauvres, quel bien en attendras-tu? S'ils sont opulents, tu t'exposeras à leur mépris, aux vexations peut-être d'héritiers avides dont ta présence détruira les espérances.Ga naar eindnoot27 The information will be instrumental in revealing Jeannette's true identity when a character explains how his late brother abandoned a child at his master's request. Jeannette - like an eighteenth-century foundling from Lorraine whose document is visible on the photograph - was left with a torn piece of paper, which reads: Cette enfant s'appelle Jeanne Vic...

baptisée le jour d'hier; mais sa nais...

son père. Si vous plaignez la cru...

défaire, n'accusez ni son coeur ni...

sa mère. La fatalité qui a poursui...

sera peut-être de les persécuter. Un jour,...

trouvés, où l'on est prié de garder ce...

connaître.Ga naar eindnoot28

| |

[pagina 20]

| |

Figure 11: Torn document left with a foundling in Lorraine

The gist of the message is easy to understand. The novel adds that, as a further precision, the date of the little girl's discovery was indicated by the hospital administrator when she was brought in. A few pages further along, the two halves are reunited: Cette enfant s'appelle Jeanne Victoire Déricourt: elle a été baptisée le jour d'hier; mais sa naissance a comblé les malheurs de son père. Si vous plaignez la cruelle destinée qui le force à s'en défaire, n'accusez ni son coeur ni son indifférence pour sa mère. La fatalité qui a poursuivi ces infortunés, se lassera peut-être de les persécuter. Un jour, on se présentera aux Enfants-trouvés, où l'on est prié de garder ce précieux dépôt qu'on ira reconnaître.Ga naar eindnoot29 The infant's parents were threatened by a ‘lettre de cachet’, an arbitrary royal order for them to be imprisoned, and the foundling hospital seemed the best place to leave their child in safety. They subsequently tried, and failed, to claim her back. Her full name is restored at the end of the novel with the second half of the message giving her surname and implicitly recognising her as having a specific social identity. The two halves make the message clear and offer the means to cast light on an unfortunate event. | |

[pagina 21]

| |

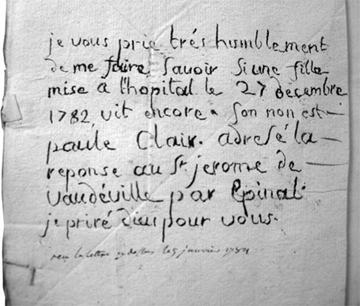

Figure 12: Letter enquiring after ‘Paule Clair’ abandoned in Lorraine in 1782

Archive holdings like those in Rouen and Nancy are full of torn documents, cut ribbons and half medals which are testimonials to children who never regained their birth identity, either because they were not claimed by their parents or because they died too soon. There are also, more often than one might have thought, letters from people enquiring after a child abandoned years earlier - sometimes even one who was left without a message or any identifying object. This tends to show that the easy equation between child abandonment and lack of instinctive maternal love, defended by certain philosophers, even nowadays - I am thinking in particular of Elisabeth Badinter's study L'Amour en plus (Paris, Flammarion, 1980) - cannot reliably use eighteenth-century foundling statistics as evidence. There are touching letters in the archives, written by parents whose circumstances have changed, women who have married - their child's father or another man whom they have made aware of their previous pregnancy - or the extended family of the foundling, attempting to discover the whereabouts of one entrusted to the hospital. Often they show consciousness of the high mortality rates for infants and enquire as to whether, like ‘Paule Clair’, a little girl born in Lorraine, their offspring are still alive. Some talisman-like tokens, intended to identify a foundling one hoped or expected to recuperate, may have given indirect hints as to the child's identity. One, like an unfortunate 4-year-old who was left on April 20th 1789 with a piece of stiff paper, which had obviously served for pins or needles may well have been the child of a pin- | |

[pagina 22]

| |

maker or a seamstress - or at least from a family with some ties to garment-making, the piece of professional detritus being a means to mark him out.Ga naar eindnoot30 One whose note included a quotation from a poem may have been born to a mother and/or father who had received advanced schooling.  Figure 13: Card from pins or needles left with a foundling in Rouen on April 20th 1789

| |

Writing on the bodyNowadays of course DNA-testing makes things a lot clearer. At a time when the scientific study of human morphology was in its infancy, a child's facial and bodily characteristics were rarely observed.Ga naar eindnoot31 If - as I have - you read through all the reports of foundlings in Rouen in the eighteenth century - bearing in mind that in 1789 alone, admittedly a record year for pre-revolutionary times, there were 719Ga naar eindnoot32 - you can but be struck on the one hand by the exquisite detail given of any clothes the child was wearing: colours - from the mundane ‘bleu’ or ‘rouge’ to more unusual ‘couleur de chair’, ‘couleur cendre’ or ‘couleur merdoie’ as quoted supra; types of cloth - there are over thirty kinds mentioned, sometimes with geographical provenance (Silesian cloth) or a particular function (winding sheet cloth)Ga naar eindnoot33 -, state of wear, shapes etc. at a time when baby garments, particularly in the poorer classes, were often gaudy patch- | |

[pagina 23]

| |

works fashioned out of bits of adult clothing like cuffs or sleeves. However there is no mention of physical characteristics, certainly for infants, unless they are ‘sickly’ or ‘dying’ or have some kind of visible handicap like a withered limb or a missing finger. Children were not weighed. There is no mention of them having a shock of hair or being bald, of the colour of their eyes etc. For a parent to be absolutely sure of getting back his or her child, nature could have helped if the infant had any kind of distinguishing feature like a birthmark. Otherwise the mother or father would have to take affairs into his or her own hands by branding the child as a farmer would his livestock. Archival evidence suggests that such practices existed in different walks of life. An unknown infant was abandoned in Rouen with the following message: ‘il est né aujourd'huy un enfant mâle qui est marqué sur La poitrine a droit de quatres fourchons de fourchettes on prie ces dames de Le faire baptiser et de Le nommer jean françois et on prie ces d'ames d'en avoir bien soin fait a roüen Le premier juillet 1775’.Ga naar eindnoot34 The child had not been christened. He had been marked. His parents were implicitly stating that their possibility of recognising him was more important than his baptism in a country in which Catholicism was the state religion, and identity was founded on parish registers. In a sense, whoever marked little Jean-François was using the age-old means of identifying the infant: creating that which passports used to call ‘distinguishing marks’. A literary parallel comes to mind, that of Ulysses' return to Ithaca. The first to recognise him was his old nurse who, called upon to wash his weary feet, could not fail to notice his scar. The second true case I should like to discuss briefly was the eighteenth-century equivalent of a sensational tabloid story. It involved a clandestine birth, a noble family, various accomplices and questions of inheritance. It is referred to in letters and newspapers but I initially came across it when reading the diary of Mathieu Marais, a chronicler of Parisian life in the first half of the eighteenth century.Ga naar eindnoot35 His entry for August 9th 1724 reads as follows: On a parlé d'une découverte faite dans l'affaire de Choiseul. Leduc, accoucheur, a tenu un registre des femmes qu'il a délivrées, et là, il a écrit qu'un tel jour, il a accouché Mme de Choiseul d'une fille, qu'il l'a fait baptiser à Saint-Étienne-du-Mont sous le nom de Julie et sous de faux noms de père et de mère; qu'il l'a portée à Meudon en nourrice; qu'il lui a fait trois incisions sous le jarret, où il a mis de la poudre à canon, pour servir à la reconnaître, et qu'il a fait tout cela à la prière de Mme de Choiseul. Ce registre s'est trouvé entre les mains de son neveu qui l'a porté chez un notaire. On a été à Saint-Étienne; on y a trouvé l'extrait de Julie; on a regardé sous le jarret: les incisions y sont. Sur cela, on crie miracle; et moi, je dis que tels registres doivent être brûlés et qu'il n'est pas plus permis à un accoucheur d'écrire ses secrets qu'à un confesseur la confession de son pénitent.Ga naar eindnoot36 | |

[pagina 24]

| |

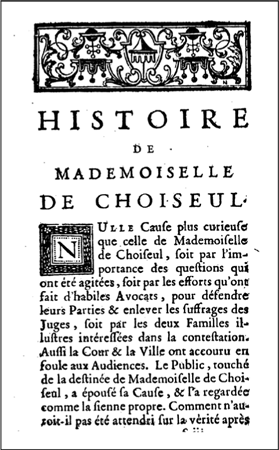

Let us leave Marais the responsibility for his judgement regarding medical secrecy versus public interest - though it does clearly indicate that identities can be hidden - but notice that the infant was tattooed in such a way as to make it impossible for her to be swapped for another girl. According to further entries in the diary, she may have been legitimate, but the child of a harsh father, the duc de Choiseul, who already had two daughters and did not want to share out the inheritance he hoped to leave to a son. Clearly, the idea was for the new-born child not to be mixed up with another, which is why she was marked, but it posed numerous questions. As a legal commentator observed: ‘On ne prend point de pareilles précautions pour conserver l'état d'un enfant qui naît dans le sein de la légitimité’.Ga naar eindnoot37 The conclusion is a sweeping one. It does underline the fact that such marking would not be necessary for a child brought up at home, by his or her parents: ‘ces marques ignominieuses [...] ne conviennent qu'à un enfant de ténèbres’.Ga naar eindnoot38 It is only when the doctor's register was discovered that ‘Julie’ aka ‘Mlle de Choiseul’ found out why she bore the mark, which was ‘imprimée réellement sur son corps’ - truly imprinted on her body -, a mark, which was clearly designed to identify her and is described by a commentator as ‘un signalement de reconnaissance si evident, qu'il ferme la bouche à l'incrédulité même’.Ga naar eindnoot39 Beyond the recourse to witnesses, whose reliability in identifying individuals was questioned in the course of the trial, the scar (as explained by the doctor's diary) was one of the elements used to ascertain the validity of Mlle de Choiseul's claim to her ducal lineage and inheritance as the judgment rendered on April 13th and June 6th 1726 shows.  Figure 14: Extract from the 1786 edition of the Causes célèbres et intéressantes

In many cases where children were abandoned because they were illegitimate, their parents cared for them from afar, providing money for a wet-nurse, for instance, even when they did not own up to their identity. | |

[pagina 25]

| |

‘Julie’, Mme de Choiseul's daughter, was neither totally abandoned, nor afforded her birth-right - she was known as Mlle de Saint-Cyr, not a family name, and care for her was entrusted to a noblewoman close to her mother. No substitution of another girl, by someone seeking to claim a pension or reward, would have been possible thanks to the de facto tattoo on her knee. Fiction offers examples of children being marked. The most famous one is Beaumarchais' Figaro; he bears a blemish on his arm, which allows his parents to identify the adult he has become: Bartholo: Le fat! c'est quelque enfant trouvé! Figaro is Emmanuel - ironically ‘God with us’. Whilst the objects found with him are evidence of his identity, the scar is proof - as it was for the duchesse de Choiseul's daughter. It was created when his father, a medical student, branded him with a surgical instrument. Its ‘raison d'être’ and meaning become clear thanks to external ex- | |

[pagina 26]

| |

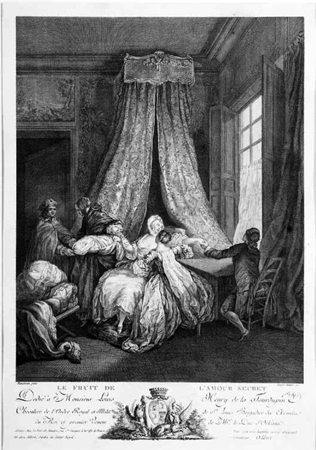

Figure 15: Baudouin, Le Fruit de l'amour secret, engraved by Voyer

| |

[pagina 27]

| |

planations, offered here by Marceline, his mother, in the same way as it only became clear to the duchesse de Choiseul's daughter why she had a tattoo on her leg when she read the accoucheur's notes about her birth. Figaro/Emmanuel has known both his parents but never recognised them as such, the ‘cri de la nature’ or ‘cri du sang’ has not rung out. Beaumarchais' late Enlightenment play shows a jaded approach to traditional tales in more ways than one. Figaro's dreams do not materialise. He does not have rich parents. He was not kidnapped for money. The mark confirms his illegitimacy, not his nobility. It ties him in to a family of surgeons by its very shape. | |

The call of NatureThe reference to nature which Marceline mentions, shows a third way in which Enlightenment societies thought of identity, beyond documentation and physical characteristics. They believed it in many ways to be innate. A child like the fictional Jeannette, whom I mentioned earlier, was wise beyond her years and, in a sense, whilst only small, possessed of a character, which set her apart from other foundlings. Implicitly, at the time, this would have been interpreted as the result of her being legitimate and from an honourable family, rather than the product of a casual relationship or a rape. This inner character, visible in her bearing, feeds in to the ‘nature vs nurture’ debate. It implies that there are true ties between a child, even cast out at birth, and his or her genetic family. Modern stories of twins separated as infants and brought up in different homes, often without knowing they had siblings, sometimes point to curious connections: they give their own children the same names, pursue the same course of studies, enter the same professions or, more mundanely, choose the same curtain material. In the eighteenth century, it was believed that one's blood could not remain insensitive to such close connections. In 1767, at the Salon of the French Royal Academy, Baudouin exhibited a painting the famous artist Chardin was to own. It showed a scene taking place in a well-appointed room. A midwife is handing a bundled-up child to a man in a cloak and hat whilst the mother who has just given birth, and the father who holds her hand are obviously reluctant to let it go. The title was Le Sentiment de la nature cédant pour un temps à la nécessité [The sentiment of nature giving way, for a time, to necessity], implying that parental feelings run high, but that the context made keeping the child at least temporarily impossible to envisage. The picture was engraved under a new title, Le Fruit de l'amour secret, and obviously struck a note with a number of contemporaries. Another Baudouin picture, La Fille qui reconnaît son enfant à Notre-Dame parmi les Enfants-trouvés, ou la force du sang, which Diderot comments on at length in his 1765 Salon, elaborates on this instinctive maternal love. Diderot suggests that rather than paint the girl holding and kissing her child, whom she has recognised in the foundlings' pew at the cathedral in Paris, this is what the artist should have shown: | |

[pagina 28]

| |

Veut-on faire sortir la force du sang dans toute sa violence et conserver à la scène son repos, sa solitude et son silence? voici comme il fallait s'y prendre et comme Greuze s'y serait pris. Je suppose qu'un père et qu'une mère s'en soient allés à Notre-Dame avec leur famille composée d'une fille aînée, d'une soeur cadette et d'un petit garçon. Ils arrivent au banc des enfants trouvés; le père, la mère avec le petit garçon, d'un côté; la fille aînée et sa soeur cadette de l'autre. L'aînée reconnaît son enfant; à l'instant emportée par la tendresse maternelle qui lui fait oublier la présence de son père, homme violent à qui sa faute avait été cachée, elle s'écrie, elle porte ses deux bras vers cet enfant; sa soeur cadette a beau la tirer par son vêtement, elle n'entend rien. Pendant que cette cadette lui dit tout bas: Ma soeur vous êtes folle, vous n'y pensez pas; mon père... la pâleur s'empare du visage de la mère et le père prend un air terrible et menaçant: il jette sur sa femme des regards pleins de fureur et le petit garçon pour qui tout est lettre close, bâille aux corneilles. La soeur grise est dans l'étonnement; le petit nombre de spectateurs, hommes et femmes d'un certain âge, car il ne doit point y en avoir d'autres, marquent, les femmes de la joie, de la pitié, les hommes de la surprise; et voilà ma composition qui vaut mieux que celle de Baudouin. Mais il faut trouver l'expression de cette fille aînée, et cela n'est pas aisé.Ga naar eindnoot41 In this example, the mother has no doubt who her child is. She has what we would call, in demotic English, a ‘gut feeling’. Obviously, however, there was a modicum of uncertainty if you returned five or ten years after abandoning your child to take him or her back: there could have been a mix-up at the hospital and there were cases of dishonest nurses substituting infants for others to ensure they received payment for their services even if their original charge had died - this was why special numbered collars were fitted to foundlings and there were even plans in certain institutions to mark them physically.Ga naar eindnoot42 Referring to Mme de Luxembourg's attempts to locate his firstborn, Rousseau admits to his worries: Si à l'aide du renseignement [his copy of the cipher] on m'eût présenté quelque enfant pour le mien, le doute si ce l'était bien en effet, si on ne lui en substituait point un autre, m'eût resserré le coeur par l'incertitude, et je n'aurais point goûté dans tout son charme le vrai sentiment de la nature.Ga naar eindnoot43 As Diderot and Rousseau's remarks show, eighteenth-century commentators took the question of nature and inner feelings in ascertaining identity seriously. Just before the start of the century, it was used as means to confirm blood ties between a mother and her adult child in a court case in Lille in 1696. Recognition was based on various elements but feelings are presented as paramount in this indication of the mother's reactions: | |

[pagina 29]

| |

elle recoynoissoit la même Anne Fouré pour sa fille naturelle, [...], et de l'avoir engendré des ouvres dudit Charles Fouré et mis au monde dans la forme et manière prescrite et prédite, adjoustant de plus que icelle Fouré saditte fille resemble à son père Charles Fouré dans les traits du visage pour laquelle elle confesse et dépose de ressentir toute la tendresse, mouvements et marques naturelles d'une mère envers son vrai et véritable enfant, et que c'est la même Anne Fouré qu'elle déclare et institue héritier universelle de ses biens, comme elle a déclaré et institué par son testament du 22 mars 1672.Ga naar eindnoot44 Anne looks like her father Charles Fouré. The mother's feelings and family likeness had also been an important factor in recognising the identity of Bernard, comte de Saint-Géran et de La Palice (1641-1696), who had been kidnapped at birth by jealous relatives and christened under a false name. As there were titles and properties involved, a trial was necessary for his rights to be recognised, which they duly were, by Parliamentary decisions in 1663 and 1666. Such public cases sparked much debate and the question of how to ascertain a child's parentage was hotly contested. As Fontenelle recalls, alluding indirectly to the Saint-Géran affair: ‘Les uns tiennent pour la ressemblance contre la certitude de la naissance, les autres pour la certitude de la naissance contre la ressemblance’.Ga naar eindnoot45 The Parisian archives even indicate an extraordinary eighteenth-century case in which a familiy was called upon to identify a foundling simply by instinctive reactions in the absence of sufficient clues.Ga naar eindnoot46 This shows that there were two possible ways of ascertaining who an individual was, apart from circumstantial or documentary evidence (like the ribbons and notes left with foundlings): by his outer self, his build, colouring, features and so on, which could be read or deciphered just by looking at him, or by relying on internal feelings which went beyond the rational. | |

Found(lings) in writingAs some of the parallels I have drawn between archive material and fiction show, foundlings played an important role in Enlightenment literary imagination, and I should now like to turn briefly to that aspect of things. It is worth recalling that a Latin name for a foundling is ‘inventus’, the discovered one, but also the invented one. Referring to a word used to denominate a writer who chooses prose over verse, ‘Prosateur’, which was created by Ménage, Dominique Bouhours, a famous grammarian, observed that ‘ce mot n'est pas un de ces enfans trouvez, dont on ne connoit ni le père, ni la mere’.Ga naar eindnoot47 In addition, a figurative meaning for ‘Enfant trouvé’ as included for instance in the 1752 ‘Supplément’ to the Dictionnaire de Trévoux, was that of a newly rediscovered author or text.Ga naar eindnoot48 Certain commentators, from the eighteenth century to the present, have stated that Rousseau's offspring never existed.Ga naar eindnoot49 He is said to have passed off as his own children whom Thérèse Levasseur may have had with others, or even to have invented the five foundlings for various reasons, possibly to cover up his own sexual inadequacies. Paule Ada- | |

[pagina 30]

| |

my-Fernandez, one of the more recent exponents of the theory that the abandoned children were wholly fictitious affirms that: ‘Rousseau, en un mélange de conscience malheureuse et de certitude d'innocence, a inventé des enfants abandonnés’.Ga naar eindnoot50 Let us suppose, for an instant, that she is right. Rousseau's imaginary foundlings could thus be equated with his literary works: they are products of his imagination. We know he attempted, on February 24th 1776, to abandon the manuscript of his dialogues, Rousseau juge de Jean-Jacques by the high altar in Notre-Dame - the cathedral in which the Parisian ‘enfants trouvés’ had their pew -, and foundlings were often left on an altar or on the steps of churches. The work was given its own letter of introduction, which starts in a way not dissimilar to notes found with some abandoned children: Protecteur des opprimés, Dieu de justice et de vérité, reçois ce dépôt que remet sur ton autel et confie à ta Providence, un étranger infortuné, seul, sans appui, sans défenseur sur la terre, [...] daigne prendre mon dépôt sous ta garde, et le faire tomber en des mains jeunes et fidèles.Ga naar eindnoot51 One might add that Rousseau, who was unable to abandon the manuscript as the high altar was not accessible on the very day on which he chose to make his way there, is more specific about the date on which he attempted to leave his work, and the text of the note he was intending to leave with it, than about the children he abandoned at some imprecise time, one of them with an undisclosed cipher, the others with nothing to distinguish them... Etymologically, a ‘plagiarist’ is one who steals children: the equation between the child and the written work is a common one. Besides the tradition of depicting the begetting of an artist's oeuvre as similar to giving birth or of using the metaphor of rediscovery to justify referring to written works or their authors as foundlings, the launching of a text into the wider world is sometimes presented as akin to abandoning a child to the mercy of society - the analogy I proposed for Rousseau is not a mere conceit. A book with a title page, by a famous author, is like a foundling left with its full identity and complete sets of clothing. Anonymous works are more like infants left naked on a backstreet, their parents fearing they might disappear without trace, but hoping to see them picked up by a rich patron. Encouraging him to recognise his Essay on the right of property in land, Thomas Reid wrote to William Ogilvie on April 7th 1789: ‘Mr. George Gordon [...] is much pleased with An Essay on Landed Property, and cannot see a reason (neither can I) why it should go about like a foundling without its father's name’.Ga naar eindnoot52 Failure to recognise one's writings could lead to them being claimed by others. Voltaire complained in a letter to his friend Nicolas Claude Thieriot, dated 17th June 1770, that, in Paris, people often made wild guesses at the fathers of abandoned children, that is of anonymous works. The term is also used by the authors themselves about their own texts. In 1760, the marquis de Caraccioli, a defrocked Oratorian who wrote a number of books, from | |

[pagina 31]

| |

religious essays to epistolary fiction, addressed his very own Livre à la mode in the following terms: ‘Je vous abandonne comme un enfant qu'on expose, qui devient tout ce qu'il peut, et dont on ne connaît point la mère’.Ga naar eindnoot53 Brument, in a novel whose title underlines the success of Rousseau's own bestseller Julie ou La Nouvelle Héloïse, to which he pays lip-service from the outset, Henriette de Wolmar ou la Mère jalouse de sa fille, makes a similar remark in his ‘Avertissement’: ‘c'est un bâtard que j'expose;Ga naar eindnoot54 qu'il devienne ce qu'il pourra’.Ga naar eindnoot55 The work is a bastard child of Rousseau's imagination since it is Brument's imitation, not the master's work. It might please the public who could not get enough of Julie and Saint-Preux's adventures. It might, on the other hand, not make its mark, like a foundling dying in infancy. To give another, slightly later example, a post-revolutionary pamphlet includes a ‘Lettre d'envoi ou passeport donné à cette brochure pour se rendre chez MM. les Rédacteurs des Journaux’ signed by its (purported) author: Messieurs,  Figure 16: Note with a Biblical quotation (Foundling Hospital, London)

| |

[pagina 32]

| |

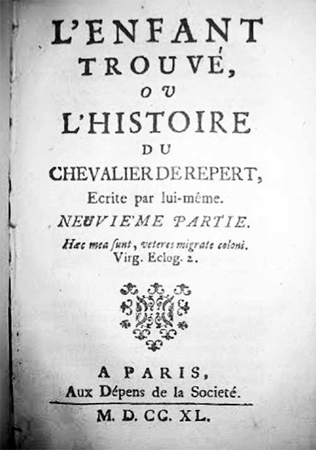

J'ai l'honneur d'être, Messieurs, avec la considération la plus distinguée, Votre très humble serviteur, The identity of the author - the father - can be disclosed in the fullness of time. Montesquieu for instance revealed that he was the author of the anonymous Lettres persanes after they had met with popular success and become, in a sense, a child he could recognise with pride. The prefatory letter signed Villiaume bears some resemblance to the notes left with actual foundlings and which enclose fragmentary elements of information.  Figure 17: Title page of a volume of the anonymous L'Enfant trouvé, ou L'Histoire du chevalier de Repert

It could be added that one of the ways to become famous in the republic of letters in the eighteenth century was to take part in academic contests. Both Voltaire, who submitted a commended poem to the French Academy, and Rousseau, whose first Discours, the one on Sciences and Arts, was written in answer to a question posed by the Académie de Dijon, used such an approach as part of a career strategy. Participants had to submit their texts anonymously. Their name was replaced by a ‘devise’, that | |

[pagina 33]

| |

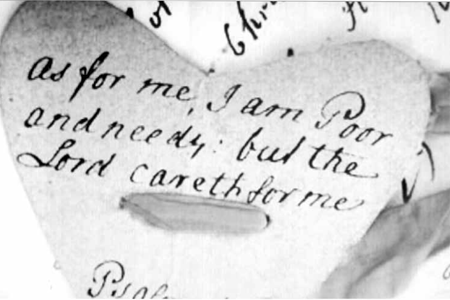

is a short sentence, usually a quotation. Voltaire, for instance, used a line by Virgil for his 1714 poem, an ‘Ode sur le voeu de Louis XIII’. Others used Biblical texts like extracts from the Psalms. In academic competitions, the author's name - assuming he chose to admit to it - was then indicated in a separate envelope, which bore the same quotation. It would only be opened if the submission was awarded a prize. Parents leaving their child with a note which is sometimes a simple sentence like ‘Guidez ma jeunesse’, the words embroidered in silver on baby Louise Victoire Polycarpe's blue silk bracelet, could act in exactly the same way as wannabe writers: it was up to them to decline their full identity if they so wished. As an English example, ‘As for me, I am Poor and needy: but the Lord careth for me’, on a blue heart-shaped paper with a pink ribbon indicates, as far as foundlings were concerned, the practice was not confined to France. As Jan Herman has pointed out in his perceptive study Le Récit génétique au XVIIIe siècle, prefaces of Enlightenment novels are often misshapen pieces whose origin is not really stated, and they precede fictional tales of foundlings, as though the paradigm of the abandoned child was both generically right to describe the contents and the ideal subject matter for the tale itself.Ga naar eindnoot57 This would appear to be more than a mere coincidence, as though the generic proximity to a metaphorical foundling made the fate of such a hero the ideal subject matter for novels of the time. We all know Marthe Robert's proposal to classify literature according to two primeval structures, the one based on the narrative of the foundling, the other on that of the bastard. The foundling escapes from reality and invents a new world in which he can believe he has rich parents and will ultimately come into his birth-right. Otto Rank pointed out the importance of the foundling myth in many heroic and religious traditions - figures like Moses spring to mind for the major monotheistic faiths and Cyrus or Romulus and Remus for political narratives.Ga naar eindnoot58 One could add that foundlings are major characters in many early works of fiction, whatever the literary tradition, as when Diodorus Siculus wrote of Semiramis or when Heliodorus penned Theagenes and Chariclea. In fictional foundling narratives, the tale is usually one of triumph over adversity. For instance in L'enfant trouvé, ou L'histoire du chevalier de Repert, Écrite par luimême, a 1738 novel, we know from the title that all is well: the former foundling has become the ‘chevalier de Repert’, an individual with a name and an identity, and a nobleman to boot.Ga naar eindnoot59 There is no suspense in that respect: the reader will find out how he goes from being an abandoned child to a knight of the Realm, but will not worry that he might remain anonymous. There are fewer tales, like Kleist's subsequent Der Findling (The Foundling), written circa 1805-1806, in which the child is the image of external infection spreading to a healthy body. As a result, stories about foundlings are, on the whole, reassuring ones, which tend to suggest that you cannot be deprived of your birth-right and true identity, even if the odds are stacked against you from the start, but also that your own feistiness, like that of Marivaux's Marianne, will ultimately pay off. Literature is play- | |

[pagina 34]

| |

ing its traditional role of showing that you should not expect the worst and that there is a better life to hand, at least in the world of fiction.  Figure 18: Document allowing Michel Auguste to be fostered by François de Lavoix (Rouen, 1792)

As a genre, the Enlightenment novel was without true letters patent, unlike tragedies, for instance, or epic poems, whose roots and genealogy stretched back through the centuries to Antiquity, shaped by great practitioners and by literary theorists like Horace or Aristotle. It was, in many ways, a bastard form or at least a genre with dubious parentage that had sort of happened and come to particular prominence in Enlightenment Europe, because its narrations, in particular of the fate of seemingly ordinary human beings, hit the right note at the time:Ga naar eindnoot60 eighteenth-century novels increasingly examined the individual's path just as the individual was becoming responsible for his or her own destiny. The downfall of Louis XVI, put to death, according to the narrative produced for his contemporaries, by the collective will of his people - his metaphorical children - turned the French into orphans, de facto. It was in some ways the culmination of the archetypal novelistic narration in which the child, like Marivaux's Marianne, had to overcome obstacles and regain his or her identity. The | |

[pagina 35]

| |

difference was that there was no longer an inheritance or a family to discover, rather the discovery had to be that individuals were to stand on their own two feet, not as children of anyone. Freudian psychology grants the figure of the foundling considerable importance, showing that, as part of growing up, individuals will pass through a process in which they deny reality and fantasize that they could be someone else's child, that they do not belong with parents whose faults they grow to see all too clearly after having adulated them. | |

Whose child are you?If one connects these fictional stories and psychological archetypes to the world-shattering events which followed the storming of the Bastille on July 14th 1789, with the execution of the king on January 21st 1793,Ga naar eindnoot61 one can only wonder at the possible consequences of the conception of fatherless children - artificial insemination means that in many cases the identity of the sperm-giver is not known - and recourse to surrogate mothers. At a time when DNA can tell each of us precisely where our ancestors hailed from and whose hair was left at a crime scene, paradoxically modern science is creating generations of semi-foundlings - not just in the conventional sense as baby-boxes, child abandonment on doorsteps and so on concern far smaller numbers than in the eighteenth century,Ga naar eindnoot62 but in the sense of individuals who are deprived of some of the knowledge to which most of us have access about our parentage.

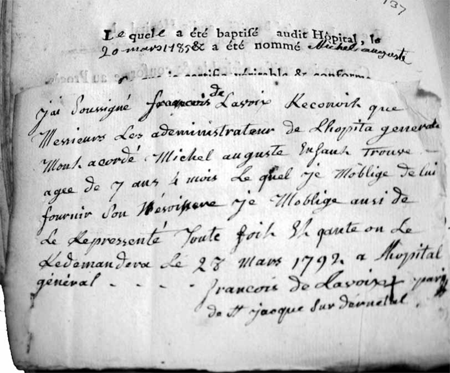

Foundlings were sometimes released by hospitals in the eighteenth century. In 1780, in Rouen, the marquis Denel, equerry to the king's sister-in-law and colonel-in-chief of an infantry regiment, applied successfully to adopt little Marguerite Anne Rose, a 5-year-old girl who had been abandoned some years earlier at the hospital gate. The official documents salute his generosity and judge that the child was particularly deserving of his attention, ‘la nature l'ayant partagée d'une figure agréable et intéressante’.Ga naar eindnoot63 Were this a novel, she would probably have been his illegitimate daughter. Nothing allows us to know whether there were in fact any connections between the marquess and the foundling, or whether he was simply obeying Enlightenment codes of sensitivity and gratuitous benevolence. Such generous gestures sometimes led to a happy life for the foundling. Madeleine Belliard, for instance, was withdrawn from the Paris foundling hospital, at the age of 5 years by the duchesse de Tallard. She spent 18 years with her patroness and married Jean-Michel Bullot, described as a ‘bourgeois de Paris’. Madeleine Belliard was given a job in the Royal household, tending to linen for the princes. When Louis XVI became king, he rewarded her for her services. It is unlikely she would have had such a career had she remained in care.Ga naar eindnoot64 At times, too, the foster parents who had been paid to bring up the child applied to keep him or her as part of the family. Such applications were usually granted conditionally, the hospital retaining the right to call the foundling back, for instance if the birth parents wished to recuperate him or her, as in 7-year-old Michel Auguste's | |

[pagina 36]

| |

1792 document, which the adopting father, François de Lavoix of Saint-Jacques sur Darnétal in Normandy, has signed with a cross.  Figure 19: A mother abandoning her baby in a foundling wheel (Nouveau Larousse illustré, 1898)

Regarding the question of who can claim a child, there is an interesting case in Rouen in January 1788: rich but as yet unmarried parents entrusted their new-born | |

[pagina 37]

| |

daughter Suzanne Augustine Elisabeth to the surgeon present at the birth, Blanche asking, that she be left at the foundling hospital with a luxurious trousseau, a note, a length of pink ribbon and funding for her upkeep. It was always intended they should claim her back. The Mother Superior was not impressed by Blanche calling for the child a few months later and refusing to own up to the names of Suzanne Augustine Elisabeth's mother and father who had left to get married in Paris as soon as they could:Ga naar eindnoot65 he stated that as he had left the child, he alone could sign the disclaimer on her being released by the foundling hospital. He would be the only person, apart from the parents, able to connect the daughter of a well-heeled married couple with an illegitimate foundling. One can but feel that the Mother Superior was motivated by the same prurient curiosity which makes modern readers rush for their copies of the latest scandal sheet to read about the king of the Belgians' illegitimate daughter or whether Justin Bieber really has fathered a love-child: she was interested not in returning the right infant - there was no apparent problem in locating her -, but in knowing the girl's true identity and birth-right. Excessive precautions were taken in Suzanne Augustine Elisabeth's case. The layette left with her had shown that she was the child of wealthy parents. In Ducray-Duminil's novel, which I quoted, little Jeannette, who had been abandoned naked in an alley-way, is, unlike Michel Auguste referred to earlier, adopted by Monsieur and Madame d'Eranville ‘sans que père, mère, supérieurs quelconques, aient jamais le droit de la réclamer’.Ga naar eindnoot66 To a modern reader, the conditions are problematic: the child is being assigned to a foster family and, with no form of consent, renouncing her birth-right should her flesh and blood relatives come forward. There are echoes for us of cases like those of the Haitian ‘orphans’ due to be flown out to the United States by a Baptist group from IdahoGa naar eindnoot67 in the aftermath of the 2010 earthquake. They were discovered in most cases to have living relatives unaware of their possible departure. There are also I think elements to ponder with regard to current overseas adoptions. It is not for me to go into the obvious psychological trauma, which any abandoned child must feel. I am sure that future neuro-scientific research will demonstrate the importance of what the child hears or feels in utero and possible influences of things as different as the food his or her pregnant mother ate, the language(s) spoken around him or her, or indeed the climate in which he or she lived whilst still in the womb. I am more concerned here with the problem evidenced by Jeannette's case: the decision to sever all ties with a child's birth family, with or without consent. The intense, one might say conjoined or fused relationship between mother and child is obvious in some of the messages left with eighteenth-century foundlings through the choice of pronouns: often the person writing the note will do so in the child's name, using a first-person pronoun. There are many such instances: ‘Je suis née de ce jour 11eme fevrier 1777 à une heure après minuit. Je demande le baptême et pour nom Scolastique’.Ga naar eindnoot68 There are also cases in which, movingly, the same pronoun is used for mother and child: ‘Je suis Baptisé du dix-huit septembre 1775 Je mappelle | |

[pagina 38]

| |

Jean Baptiste Bernard je pris ses dames en cas qu'il soit Baptisé qu'il lui fasse porter Le mesme nom Je prie ses Dames d'an avoir soin’.Ga naar eindnoot69 The three first first-person pronouns (Je, je, m') are to be attributed to the newborn child. The two subsequent occurrences of ‘je’ refer to the mother's requests. I would contend that these sentence structures, which would make the brief message difficult to parse, are clear indications of a relationship in which mother and child are still one in many ways, as they have been for the 9 months of gestation. It seems to suggest that, metaphorically speaking, the umbilical cord has not been cut. I believe that this purely grammatical observation denotes psychological realities for the mother, but also for the child for whom total severance from his or her mother in the immediate after-birth can only be a wrench with potentially serious consequences. There is, I think, another aspect to consider with that of foundlings and identity: it is the question of the extent to which knowing one's genetic past is a right. Many of us know that we have poor circulation like our paternal grandmother or a good singing voice like our maternal great-grandmother. Imagine going along to the doctor and being asked about whether there is a history of heart disease or cancer in your family. Most of us can readily answer the question for our parents, grandparents, aunts and uncles, brothers and sisters. If you do not know your identity, you cannot. A foster parent or an adoptive parent may have lavished great love and attention on you - more perhaps than your birth parents would -, but he or she will not be able to account for your genetic makeup, whether in regard to the colour of your eyes or the incidence of asthma in your family. Obviously if you have been found on a doorstep and no manner of enquiries makes it possible to ascertain your parentage - or in circumstances similar to the eponymous heroine of Marivaux's La Vie de Marianne who survives a terrible carriage accident in which her mother is killed - there is no solution. In a not so distant past, young women in Ireland who became pregnant when unmarried were sent to homes where they gave birth and were forced to let their baby be taken away, often with no possibility of seeing them ever again or maintaining any kind of contact. In Franco's Spain, religious orders would pretend that the offspring of families with suspicious political tendencies had been stillborn and farm them out to be adopted by upstanding members of the community. The same thing happened in various South American countries - in Argentina the ‘Grandmothers of the Plaza de Mayo’ aim to locate children wrongly taken from their families - often opposition activists who disappeared or were put to death during the 1976 to 1983 dictatorship. They recently announced that Pablo Javier Gaona was the 106th they had recovered.Ga naar eindnoot70 Forced adoptions may be rare, but they are obviously to be condemned. | |

Secret LivesDNA-testing has, in various cases, like that of Pablo Javier Gaona, made it possible to confirm, more accurately than any torn playing card or piece of ribbon, the identity of children adopted sometimes without parental knowledge. Beyond these startling | |

[pagina 39]

| |

cases in which consent was, more often than not, not given, the question remains of assessing at once the child and the parent's rights. In systems like the Babyklappe or Babywiege set up in Germany, a child can be abandoned, with no questions asked. He or she will be given a legal identity but have no means of finding out who his or her birth parents were. These baby-boxes are intended for desperate cases: teenagers who are in fear of what their parents or teachers might say, women from ethnic minorities in which sex outside marriage is still frowned upon and so on. They are, like the foundling wheels of yesteryear, ways of making sure that the child has every chance of surviving, which might not be the case were he or she to be dumped on church steps. The German ethics committee has expressed concern about the negation of children's rights if they are abandoned in a Babywiege and questions have been posed by the UN Committee on the Rights of the Child.

What though of mothers who give up their child for adoption in the clinical environment of a hospital or through social services networks? Must they be prevailed upon to state who they are? Are the child's rights paramount? France has a system rather like that prevalent during the Ancien Régime in which a woman can give birth without admitting to her identity. It is called ‘accouchement sous X’ and became law on September 2nd 1941: hospitals are compelled to take in without charge, pregnant women who can decide not to indicate their identity - the point, during the war, was to protect the family's honour. ‘Safe haven laws’ or ‘Baby Moses laws’ with similar approaches exist elsewhere in the world.  Figure 20: Instructions for operating a modern Babyklappe.

| |

[pagina 40]

| |

The idea of maintaining secrecy around a person's origins supposes that someone could be harmed by the knowledge. It could be the infant him- or herself - for instance if he or she is a criminal's child or the product of a rape or incest. It could be - and indeed is more often - the child's parents, usually his or her mother. Sorry stories of so-called ‘honour killings’ in ethnic minority groups in Western Europe show that, for instance, an unmarried Turkish or Indian girl who gives birth can become the victim of primal punishment meted out by family members or their entourage. To give up a child - and try, inasmuch as possible, to pretend he or she never existed - may be the only way for a mother to survive - literally. Those who promote maintaining total secrecy tend to uphold the traditional position that infanticide can be avoided thanks to such processes - and the French system has the advantage of allowing mothers to give birth in the secure environment of a hospital, with no fear about the cost -; they are however sometimes radical feminists who feel women must not be subjected to the obligation of disclosing their identity if they give birth; they can also be staunch defenders of the ‘nurture’ side of the eighteenth-century ‘nature vs nurture’ debate, believing that the only true parents are those who bring up a child.Ga naar eindnoot71 On January 22nd 2002, Ségolène Royal, future socialist candidate for the French presidency, saw her white paper on origins adopted as law. It recognises the importance for each and every one of us to have access to our origins and history inasmuch as possible. Mothers who avail themselves of the ‘accouchement sous X’ are invited to leave any information they wish the child to know about themselves, their family, their background, in a sealed envelope entrusted to a committee dedicated to the question of family origins, the Comité National pour l'Accès aux Origines Personnelles (CNAOP). Should the child subsequently desire to make contact with his or her mother, the CNAOP will contact her, should she have left details, to ask whether she accepts the principle of communicating with her offspring, either anonymously (for instance to reveal details of medical history), or by lifting her prior request for secrecy. This allows both mother and child to draw back at any point and to decide not to go ahead with a disclosure they may feel to be painful. It seems an acceptable halfway house - at least to someone like myself who has no direct personal implication in such cases. It may appear harsh to certain mothers, if their offspring are not interested, and to some children, who may discover that nothing has been left for them, but the balance is probably the least unfair way of approaching the problem. There are cases where this possibility of encountering biological parents has led to a satisfactory relationship on both sides and not had any negative impact on the ties between the child and those who brought him or her up. | |

Overseas ‘adoptions’ then and nowInstitutionalised confinements, as in the ‘accouchement sous X’ make it easier to know the child's status than when he or she is abandoned in a public place, be it a baby-box or a hospital entrance. A foundling's future with a new family, being adop- | |

[pagina 41]

| |

ted or fostered, may depend on available details concerning his or her birth parents. The complications do not end there. Adoptions are like coins: they have a flip side. On the one hand, there is the generous interpretation: the fictional Jeannette is a foundling who is lucky enough to be taken in by a wealthy noble couple - in modern terms, a comfortably-off Western family wants to give a poor child a better future. The flip side is that the Western parents' desire for a child allows them to uproot a boy or a girl, often to give him or her a new identity - sometimes attempting to remove any obvious connection with his or her past. There are arguments in favour of this: if you are different, for instance in height, build, hair or skin colour, you may welcome the fact of being helped to blend in by not having a name, which stands out. On the other hand, surely if you have been known by a name, even before you are yourself able to use language, there must be some form of trauma involved in suddenly being called something else, even for the best of reasons. Mme de Duras' 1823 title-character Ourika bears the name of a Senegalese girl given to the princesse de Beauvau by her nephew the chevalier de Boufflers: the little girl had returned with him from Africa when she was about 2 years old in 1786. The fictional heroine, also brought back from Senegal before the Revolution and educated by a noble French family, is caught between two cultures and two societies, no longer belonging to either. Does literature not have something to teach us in this respect? And am I too much of a cynic if cases such as that of Chifundo ‘Mercy’ James, brought over to the West from Malawi, with a bedroom designed with Gwyneth Paltrow's help and Stella McCartney for Gap clothes in her wardrobe, paraded around by Madonna much as a fashion accessory, bring to mind the tale of Zamor, who was born in Chittagong - currently a town in Bangladesh - around 1762? He was Mme du Barry's page-boy, apparently gifted to her by Louis XV. He was baptised Louis-Benoît Zamor in 1770 with the prince de Conti's son, Louis-François-Joseph de Bourbon, as his godfather and the king's mistress as his godmother. She brought him up, had him educated, clothed him in fine garments - as the tailor Carlier's accounts and the boy's portrait by Marie-Victoire Lemoine show - and, by all accounts, spoiled him rotten, treating him in some ways as a trophy. He certainly lived a life of luxury as compared with that which he would have had if Mme du Barry had not taken him up. When the French Revolution came, the reader of Rousseau that Zamore had become - thanks to the learning acquired through the comtesse du Barry's liberalities -, espoused the new democratic ideals. He was to turn against his patroness and betray her to the authorities.  Figure 21: Zamor, by Marie-Victoire Lemoine.

| |

[pagina 42]

| |

When Madonna goes to Malawi and brings back a small child from a poor family, is she actually helping little David or baby Mercy? Is she not, under the guise of cultural relativism, exercising some form of 21st-century neo-colonialism not so different to that of our eighteenth-century ancestors who were proud to show off their black servants and to argue that they were much better off in Manchester or Amsterdam with fine liveries on their backs and three hearty meals a day than they would have been living half-naked and eking out a meagre existence on the African coast? Would it not be preferable - or more logical at very least -, in a case like that of Madonna's ‘daughter’ for the singer to fund schools and orphanagesGa naar eindnoot72 and allow the child to be brought up by her relatives, rather than displayed like a favourite pet or plaything? I am aware that I am taking an extreme case as an example. I do feel however that, like caricatures, it bears a profound truth. I am not sure that there will not one day be payback time for foreign adoptions, in particular celebrity ones. | |