Burgerhartlezing 2011. The Enlightenment and the Origins of Religious Toleration

(2011)–Lynn Hunt, [tijdschrift] Burgerhartlezing, [tijdschrift] Documentatieblad werkgroep Achttiende eeuw–

[pagina 7]

| |

The Enlightenment and the Origins of Religious Toleration

| |

[pagina 8]

| |

Le novateur cupide, ambitieux,

Pour gouverner, arbore l'athéisme;

Sa rage insulte et la terre et les cieux,

En ne parlant que de tolérantisme.Ga naar eindnoot6

[The covetous ambitious innovator,

in order to govern, flies the flag of atheism;

His rage insults both the earth and the heavens

by speaking only of tolerationism.]

‘Tolérantisme’ was an eighteenth-century French neologism (it did not exist in English in the eighteenth century), and it originated as a term of opprobrium. It is defined in the 4th edition of the Dictionnaire de l'Académie française (1762) as ‘Characteristic or system of those who believe that one should tolerate in a state all sorts of religions’ - a seemingly bland definition written at a moment when the French government did not officially tolerate any other religion than Catholicism.Ga naar eindnoot7 The very existence of ‘tolerationism’ as a term testifies to the growing sentiment in favor of religious toleration; ‘tolérantisme’ would not have been the subject of attack - indeed, it would not have been invented as a term - if toleration was not considered a growing menace to the status of an established religion. Those who denounced ‘tolérantisme’ also attacked the Enlightenment. Important figures associated with the Enlightenment, from John Locke and Pierre Bayle at the end of the seventeenth century to Voltaire in the middle of the eighteenth, made impassioned arguments for religious tolerance, and they all embraced the term ‘tolerance’. Bayle's 1686 book Philosophical Commentary on these Words of Jesus-Christ: ‘Compel Them to Come In’ [Commentaire philosophique sur ces paroles de Jésus-Christ: ‘Contrains-les d'entrer’] was one of the first tracts in French to use tolerance of religious difference in a positive sense, and Locke's and Voltaire's titles themselves indicate the centrality of the concept: Letter concerning Toleration (1689) and Treatise on Tolerance on the Occasion of the Death of Jean Calas [Traité sur la tolérance à l'occasion de la mort de Jean Calas] (1763).Ga naar eindnoot8 Given the association of these key Enlightenment figures with religious toleration, it is not surprising that opponents of ‘tolérantisme’ would go after the Enlightenment more generally. An underground newsletter reported in 1763 on a pastoral instruction published by the Bishop of Le Puy en Velay against ‘philosophie moderne’, a term often used at the time to refer to what was only later known as the Enlightenment: ‘Esteem for the natural sciences, a doubting spirit, tolerationism, patriotism; these are the qualities that the Bishop of Le Puy attributes to modern philosophy and that he claims to refute in his pastoral instruction’. Indeed, the bishop had fulminated against ‘tolérantisme’ for nearly 50 pages of his 300 page-long tract, calling it the principle that was held ‘most dear’ by the ‘nonbelievers’ who espoused modern philosophy.Ga naar eindnoot9 By the end of the eighteenth century, in other words, the tables had turned. Those | |

[pagina 9]

| |

who opposed toleration increasingly felt challenged. In 1775, in his very successful play The Barber of Seville, Beaumarchais satirizes those who oppose ‘tolerationism’ by linking it with a whole series of other modern values. In Act One, Scene 3, Doctor Bartholo, Rosina's narrow-minded tutor, rails against the ‘barbarous century’ in which they are living: ‘What has it produced that one would want to praise? Rubbish of every sort: freedom of thought, attraction [referring to ideas about animal magnetism], electricity, tolerationism, inoculation, quinine, the Encyclopédie, and dramas’.Ga naar eindnoot10 Beaumarchais knew as well as anyone how to take the pulse of his times. | |

Freedom of ReligionEven as religious tolerance gained increasing legitimacy, its meaning began to change. Over the course of the eighteenth century, religious tolerance gradually turned into freedom of religion and became one of several rights that we would call human rights. The very first lines in the Bill of Rights of the new United States read: ‘Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof’.Ga naar eindnoot11 Of all the rights protected in the Bill of Rights of the United States, freedom of religion ranked first. The French revolutionaries spoke of it more tentatively but with perhaps even more influence. Article 10 of the Declaration of the Rights of Man and Citizen of 1789 proclaimed that ‘No one should be disturbed for his opinions, even in religion, provided that their manifestation does not trouble public order as established by law’.Ga naar eindnoot12 The ambiguity of the formulation (‘even in religion’ and as long as it does not disturb the peace) reflected the long history of conflict over religion in France. The British North American colonies had harbored religious dissidents of all kinds from their very establishment, whereas the French monarchy had only given up its centurylong policy of eradicating Protestantism in 1787. Within months of passing the Declaration in August 1789, the French National Assembly granted equal political rights to Protestants and two years later extended them to Jews as well. Because the individual states controlled access to voting in the United States, religious tests remained in force in some states well into the nineteenth century. New Jersey, for example, refused to let Catholics hold state office until 1844.Ga naar eindnoot13 Despite these limitations, freedom of religion came to be viewed - by some people in some places - as an absolute moral good. Religious tolerance, in contrast, had originated as a compromising and compromised solution to an intractable problem. As the examples of the United States and France indicate, revolutionary upheaval played a major role in this development. Whether initially intended or not, the Dutch Revolt of the late sixteenth century, the so-called Glorious Revolution of 1688-1689 in Great Britain, and the late eighteenth-century revolutions in the British North American colonies and France marked important steps in the transformation of religious toleration into freedom of religion. In each instance, rebels had to come to terms with religious differences in their ranks and rethink the customary relationship between church and state. Revolutions created extraordinary opportunities for rethinking the fundamental | |

[pagina 10]

| |

relationships that shaped emerging national identities, including religious affiliations. The crystallization of freedom of religion as a constitutional right would not have occurred without revolutions. The late eighteenth-century revolutions in British North America and France enshrined freedom of religion in the law, but they did not invent the notion, and they certainly did not inherit it full blown from their Dutch or English predecessors. The Union of Utrecht of 1579 established freedom of conscience but not freedom of public worship for Protestant dissenters or Catholics; after the 1640s, Jews in the Dutch Republic enjoyed greater freedom of worship than Catholics or even some Protestant dissenters.Ga naar eindnoot14 The English Toleration Act of 1689 extended freedom of worship to Protestant dissenters but not to Catholics or Unitarians. The law itself justified toleration as ‘an effectual means to unite their majesties' Protestant subjects in interest and affection’.Ga naar eindnoot15 How, then, did religious freedom (as opposed to toleration) get on the agenda in the first place? Is all credit (or blame) due to the Enlightenment, as both its adherents and its detractors argued? Without unduly minimizing the impact of Enlightenment writings on the subject, I will argue for a broader explanation that calls attention in particular to the influence of visual representations of the diversity of religious practices around the world. The Enlightenment of the eighteenth century did play a major role in turning religious toleration, a grudging government policy, into freedom of religion, a human right. It did not do this all on its own, however, or all at once, or everywhere at the same time. Moreover, the doctrine of freedom of religion as formulated by thinkers and politicians neglected some of the qualities of religious toleration that would have been worth maintaining. Freedom of religion was a policy of non-interference but not necessarily one of greater accommodation. Those advocating freedom of religion simply insisted that religion was a private matter. Religious toleration, for all its defects, implied that differing religious communities had to live together, even when they did not want to do so; it emphasized accommodation within the broader community rather than the presumed privacy of religious choices. As we have seen throughout history and especially in recent years, religion rarely remains private, and acceptance of religious difference continues to be an aspiration more than a reality. It is important to avoid the pitfalls of hindsight in any historical argument and perhaps especially in this one. Freedom of religion did not grow naturally or inevitably out of religious tolerance. Freedom of religion is a fundamentally different understanding of the place of religion in a community's life. No one thinker paved the way to freedom of religion, not even Bayle, Locke, or Voltaire, because none of them could possibly have imagined the freedom of religion that would be formulated at the end of the eighteenth century. Bayle, Locke, and even Voltaire focused their arguments against intolerance, explaining why tolerance would not have the evil effects so long considered inevitable. They made essentially defensive arguments rather than positing a foundational freedom of religion. Bayle did not consider religious proces- | |

[pagina 11]

| |

sions or public worship essential to religious freedom. Locke denied tolerance to those who taught intolerance (which may or may not have included Catholics), to Muslims (because they served a foreign prince, the Ottoman emperor), and to atheists, though he argued against denying civil rights to those defined as idolatrous, including the ‘pagans’ in America.Ga naar eindnoot16 Although Voltaire argued that Christianity was uniquely intolerant among the world's religions, he did not advocate complete freedom of religion; he believed that Protestants in France should be treated like Catholics in England, that is, be allowed to practice their religion in private but not have access to public office.Ga naar eindnoot17 Freedom of religion required nothing short of a change in world view and that change was only partly intellectual, not to mention only partly successful. Vociferous and even violent reactions against toleration of religious minorities could be found almost everywhere in Europe in the eighteenth century. In 1753 popular agitation forced the English Parliament to repeal a bill for the naturalization of Jewish immigrants, and in 1780 reaction against the Catholic Relief Act led to days of rioting in London, pillaging of known Catholic properties and then government buildings, and nearly 300 deaths. This fury was directed at a Relief Act that did not allow Catholics to vote, hold public office, take university degrees or even worship freely. Half of the regional parlements (high courts) in France originally opposed Louis XVI's edict of 1787 granting limited toleration to Calvinists.Ga naar eindnoot18 The courts' opposition and a flurry of hostile pamphlets forced the government to reassure the magistrates that religious toleration was not implied by the edict. Calvinists gained the right to civil status (their births, marriages, and deaths would be officially registered), to property, and to entrance into various trades and professions except those concerned with teaching, but they could not worship in public or hold public office.Ga naar eindnoot19 In the early years of the French Revolution, when the rights of Jews came up for debate, some communities in Alsace rioted against their Jews and a few towns petitioned the government against the proposed emancipation of the Jews, urging their expulsion instead.Ga naar eindnoot20 | |

Freedom of Religion and Human RightsGiven all this opposition to religious toleration, how did freedom of religion get enough traction to make its way into the U.S. Bill of Rights and the Declaration of the Rights of Man and Citizen? It is impossible to deny that Bayle, Locke, Voltaire and a host of other intellectuals played an important role in changing the European and Euro-American view of religion. Locke, in particular, advocated drawing a clear boundary line between the civil power and religion (that is, the separation of church and state). His argument is so influential that it is worth repeating: The Civil Power can either change every thing in Religion, according to the Prince's pleasure, or it can change nothing. If it be once permitted to introduce any thing into Religion, by the means of Laws and Penalties, there can be no bounds put to it.... Whereas if each of them [the church and state] would con- | |

[pagina 12]

| |

tain itself within its own bounds - the one attending to the Worldly welfare of the Commonwealth, the other to the Salvation of Souls - it is impossible that any Discord should ever have happened between them.Ga naar eindnoot21 The ability to imagine church and state in separate spheres was an essential element in the development of a notion of freedom of religion. Locke helped put a change in world view into motion, but the change depended as well on alterations in experience more widely shared than just among a small intellectual elite. What did change over the eighteenth century and among which groups? It now seems clear that the once standard narratives, inherited from the Enlightenment itself, are flawed. Reason did not triumph over religion, and Western societies did not secularize from top to bottom. Few scholars would now argue, as Herbert Butterfield did, that ‘a colossal secularisation of thought in every possible realm of ideas’ took place at the end of the seventeenth and beginning of the eighteenth century.Ga naar eindnoot22 Although established churches lost some of their power, and educated elites began to seek secular explanations for natural phenomena and political events, religion never became an entirely private affair and certainly did not cease to matter in the lives of the vast majority of Europeans and Euro-Americans.Ga naar eindnoot23 To say that nothing changed, however, would be equally mistaken. Although secularization may have been - and still is - only partial, new ways of thinking about religion had a profound effect, at least for the educated classes of the eighteenth century. Religion became one of many categories of thought, like politics or society, rather than being the foundation of all other categories of thought. It could thenceforth be conceptualized as a manifestation of underlying cultural patterns rather than as a way of life based on an inner conviction of absolute truth. As is often the case, it was a critic of this development who made clear the radical nature of the development. Wilfred Cantwell Smith, an academic specialist in Islamic studies and an ordained Presbyterian minister, argued in his influential 1962 book, The Meaning and End of Religion, that religion was a Western concept that fundamentally distorted the meaning of religious experience. ‘Religion, as a systematic entity’, he wrote, ‘as it emerged in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, is a concept of polemics and apologetics’. It is an abstraction, a depersonalization, and a reification undertaken when ‘one does not oneself see the meaning or appreciate the point, let alone accept the validity’ of another system of belief. It follows for Smith that ‘religion can become an enemy to piety. One might almost say that the concern of the religious man is with God; the concern of the observer is with religion’.Ga naar eindnoot24 Smith is wrong on many counts, in my view, but his analysis has the virtue of calling attention to the significance of externalizing religious belief, that is, of creating the plural ‘religions’ that arises, according to Smith, when religion is contemplated from the outside. There are elements of abstraction, depersonalization, and yes, even reification, involved in this process of distancing, just as there are in the concepts of | |

[pagina 13]

| |

politics, society, and culture. In the case of religion, these elements produce not only heuristic value, as with politics, society, and culture, but also political, social, and cultural changes. For religion to become a category like the others, to lose its foundational status, meant nothing less than a revolution in world view. The legitimacy of the political, social, and cultural order then had to be built on different grounds that were not given supernaturally. Human rights - the idea that rights are inherent in human beings, not granted by an outside authority - constituted one potent response to this challenge. The notion of freedom of religion as a human right - a political, social, and cultural notion - depends on the emotional distance created by the abstraction of religion as a category. Freedom of religion would be meaningless if individuals were not conceivable as agents making choices about belief, and they could only be conceived as such if religion was something external to them. The distance required by the abstraction of religion was not produced by any one factor, such as the religious conflicts of the Reformation, the intellectual arguments for religious tolerance, or the growing knowledge of the customs and ceremonies of far distant peoples.Ga naar eindnoot25 All of these entered into the equation. I want to emphasize here the influence of sympathetic portrayals of other religions, not in the texts of those writing about the religions of the world outside western Christianity but rather in the actual pictures made of other religions. While I believe that Smith is right that religion as a category requires abstraction and even a certain depersonalization and reification, this is only a partial truth. Viewing religion as a ‘systematic unity’ or category on a par with others, only contributes to religious tolerance if it also includes an ability to imagine another religion from the inside. The observer must be able to comprehend those who practice other religions and thereby re-personalize the religious experiences of other people and undermine their reification as heretical, schismatic, pagan, savage, barbarous, immoral or ridiculous. Thus while externalization of religion opens the way to freedom of religion, internalization facilitates religious tolerance. Travel literature has long been recognized as an important influence on Enlightenment thought and, in particular, on the origins of comparative religion.Ga naar eindnoot26 It expanded exponentially as a genre across the sixteenth, seventeenth, and eighteenth centuries, and by the end of the sixteenth century, printed images - intaglio prints produced on a printing press with movable type - began to accompany the texts. Prints, in particular engravings and etchings, conveyed knowledge about other religions that could not be gleaned in the same way from texts. The immediacy and impact of prints, especially for late seventeenth and early eighteenth-century viewers, is brought home by the influential French art theorist and critic Roger de Piles. Unusually for someone writing at the time about painting, the highest of the arts, he praised the utility of printmaking, one of the lowest of the arts, in a chapter in of his 1699 book, The Art of Painting, and the Lives of the Painters: Containing, a Compleat Treatise of Painting, Designing, and the use of Prints. In addition to accurately depicting art, scientific information, or any other form of knowledge, prints ‘[i]nstruct by a more forcible | |

[pagina 14]

| |

and ready manner than Speech’. They also ‘represent absent and distant Things, as if they were before our Eyes, which otherwise we cou'd not see without troublesom Voyages, and great Expence’. Perhaps even more important for our purposes here, prints afford ‘an easy way of comparing several things together’.Ga naar eindnoot27 Prints thus could pull viewers into scenes of faraway places and strange peoples, making possible either identification or revulsion or even both at the same time. Prints, I argue, set up a simultaneous process of familiarization with strange things and, through comparison, a possible distancing from one's own habits and customs. It is difficult now to recapture the experience of early eighteenth-century people looking at prints of other religions, even those close to home. Visual images so saturate our own culture that it is hard to imagine what a print might mean in a culture where images, especially of faraway places one would never visit, were much rarer, often expensive, and located at the interface between art, diversion, curiosity, and knowledge. There is no way to definitively prove the impact of the prints that will be presented here, but a closer look at them can at least start the process of unpacking the multiple messages incorporated into them.Ga naar eindnoot28 | |

Picart and Bernard's

| |

[pagina 15]

| |

publishing circles in Amsterdam and that he had an influential intellectual agenda, especially concerning religion, religious tolerance, and also religious syncretism. The seven volumes of Bernard and Picart's big book began provocatively with Judaism and Catholicism, and in the order of publication then moved to the Americas and India, Asia and Africa, only then to turn to the many forms of Protestantism, before finally tackling Islam. No previous work had offered such a grand panorama of the varieties of religiosity; indeed few other works even deigned to consider all these forms of practice to be truly religious. No previous work had insisted on such a sympathetic rendering, especially in visual terms, of Judaism, Islam or of ‘idolatry’ in its multiple forms.  Figure 1: The frontispiece of Banier and Le Mascrier's Histoire générale des cérémonies (1741).

Since it is impossible to discuss 250 folio pages of engravings in any meaningfully systematic fashion, I have chosen to focus on five images that capture important aspects of Picart's visual program. The first of these [Figure 3] is perhaps Picart's single best known engraving, his rendition of a Passover seder of the Sephardic Jews of Amsterdam. He spent four years pleading for access to the ceremony, and the importance of it to him is evident in his signature on the lower left hand corner, ‘dessiné d'après nature et gravé par B. Picart’, which signaled that Picart himself not only drew the image from real life but also personally engraved the image. Such a signature was most unusual for him; he often signed simply as having directed the engraving though he | |

[pagina 16]

| |

sometimes took credit for the original drawing. Here he insisted on both roles. In a brief biographical note about Picart, one of the few sources available about his life, his close friend Prosper Marchand remarked on the importance of the Jewish engravings to the artist and the impact that they had on viewers at the time. When Alvaro Nuñes da Costa (known as Nathan Curiel in Dutch), a leader in the local Sephardic community, finally relented and allowed Picart to attend a Seder at his home, he also ‘had the kindness’, according to Marchand, ‘to explain very exactly to [Picart] all the details. Synagogues, furniture, clothing, ritual enclosures, etc., everything was drawn from life and since nothing had yet been done in this manner, Jews and Christians, everyone was charmed by them’.Ga naar eindnoot30  Figure 2: Title page of volume 1 of Bernard and Picart's Cérémonies et coutumes (1723)

No Christian artist had ever before depicted Jewish ceremonies in such a detailed, accurate, and sympathetic fashion. According to Richard Cohen, these images | |

[pagina 17]

| |

were considered so ‘accurate and objective’ among Jews, that they ‘became a reliable source for visually depicting Jewish life for the next two centuries’. Picart's scenes later appeared on pewter plates displayed in Jewish homes in Central Europe and are still reproduced in the present in monthly calendars, wedding invitations, and other items of commercial Judaica.Ga naar eindnoot31 The accuracy of the portrayal was enhanced by the carefully drafted captions. In this case, the caption below the engraving lists seven ritual dishes and implements and describes their role in the ritual.Ga naar eindnoot32  Figure 3: The Passover Seder (1725), volume 1, first part, page 120a of Picard and Bernard's Cérémonies et coutumes.

Picart's image is much more than an accurate, objective, scientific depiction, however. The artist clearly aimed to make Sephardic Jews of Amsterdam seem familiar, that is, much like Dutch Christian families. The warm fire in the grate, the shimmering chandelier, the beautiful display cabinet, the dining furniture, plates, and cutlery create a cozy interior scene that would be recognizable to any Dutch viewer. The quiet decorum of the family identifies it as from the prosperous middle classes. Black servants, such as the one shown here, appeared quite often in individual, family, and group portraits and signaled prosperity.Ga naar eindnoot33 Hardly anything in this scene could be considered threatening, even if the religious rituals are unfamiliar. Although the artist positions the viewer just outside the space of the scene, the viewer feels drawn in; all the faces are visible, and the spaces on either side of the servant invite access to the table. | |

[pagina 18]

| |

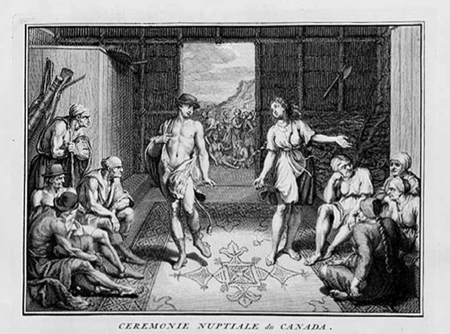

Figure 4: Canadian Marriage Ceremony, volume 3, page 92a of Picard and Bernard's Cérémonies et coutumes.

At the same time, with the caption on this engraving Picart also begins to establish the comparability of religious practices. One element of comparability that intrigued him was ritual implements. Among the 20 plates of Jewish ceremonies in volume one are no less than three full-page engravings devoted to ritual instruments and items of dress, ranging from the taled or prayer shawl to the Sefer Torah and its ornaments known as Rimonim. Picart sought out comparable ritual instruments in every part of the world. In the section on the natives of the North America, for example, he included a full page engraving of Indian ritual items that included the hut for the initiation of young men, two kinds of peace pipes, a tomahawk and a ‘casse-tête’ or instrument for cracking heads. In the section on the religion of the Lapps, he included a full page on the decorations of ritual drums alongside their hammers and ritual rings.Ga naar eindnoot34 By far the greatest emphasis on ritual elements, however, came in the long section on Catholicism that ranged across part of volume one and all of volume two. Picart included thirty-five scenes (with as many as nine scenes on one folio page) showing the different stages in the celebration of an ordinary Catholic mass, which basically reproduced prints by his Paris teacher Sébastien Leclerc, and scores of ceremonies from baptism, marriage, and funerals to rituals such as the ordination of priests based on images in the official books of Catholic ceremony in his own library, e.g., the Roman Pontifical, the Roman Processional, and the Ceremonial of Bishops.Ga naar eindnoot35 Picart intended viewers to see the similarities across the rituals, thus developing the category of religion as a cross-cultural practice, but he also rammed home the point that in certain | |

[pagina 19]

| |

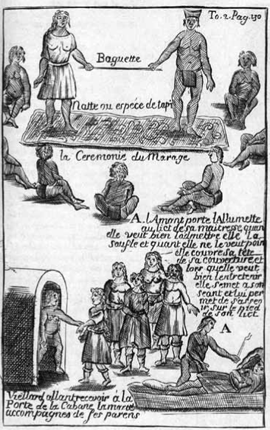

religions, in particular Catholicism, ceremonialism threatened to distort the nature of religious experience.  Figure 5: Canadian Courtship and Marriage in Lahontan, Nouveaux voyages de Mr. le Baron de Lahontan dans l'Amérique Septentrionale (1703).

Picart let his pictures talk for him. Near the end of his life he wrote a brief ‘Discourse on the Prejudices of Certain Collectors [he used the word Curieux] Concerning Engraving’, but it was entirely devoted to vaunting the virtues of fine art engraving, that is, prints of great paintings. He said nothing in it about his vast production of polemical prints or book illustrations.Ga naar eindnoot36 Yet the choices he made visually are hardly hidden. His representation of ‘Canadian marriage’ [Figure 4], for instance, speaks volumes about his views of ceremonialism. There is no priest officiating over marriage among the ‘Canadians’ (most likely the Iroquois and Hurons of New France), and the marriage is not taking place inside anything that resembles a church. Representatives of the two families sit on either side watching as the young couple, holding a kind of baton, make their promises to each other. The message is evident: marriage is universal, but the need for liturgy, clergy and churches is not. Picart's multiple aims in this image come into clearer focus when it is contrasted to the model that he must have used, a crude etching found in Baron de Lahontan's account of his voyages in North America published in The Hague in 1703.Ga naar eindnoot37 The Lahontan etching [Figure 5] is a rudimentary representation of the marriage ceremony, though it does include the baton, some kind of carpet, and the young man's hat. Other than his hat, however, the young man in Lahontan wears only a loincloth; the young woman's nipples show through her flimsy dress; and the witnesses are nearly | |

[pagina 20-21]

| |

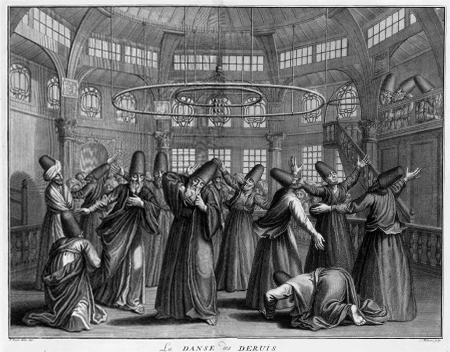

naked too. European viewers would find Lahontan's Canadians entirely strange. The contrast with Picart's rendition could not be more dramatic, for Picart has chosen to make everyone in the scene more familiar. His bride and groom have taken dance or theater postures like those known at any European court. They stand on an Oriental carpet - hardly an accurate depiction, no doubt, but it serves the purpose of familiarization. The features of the young couples' faces are clearly visible and distinctly European as are those of the family elders. The classical musculature of the men's bodies is not accidental, either, since our young man is wearing not a loincloth but a lion cloak, the classic attribute of Hercules. Picart's Canadians are not savage; they are more like heroes of the ancients or figures in the paintings and drawings of his favorite artists Rafael, Ludovico Caracci, and Guido Reni.Ga naar eindnoot38  Figure 6: The Dance of the Dervishes (1731), volume 7 pages 226d and 226e, of Picard and Bernard's Cérémonies et coutumes.

Some of Picart's images of indigenous peoples of the Americas are much more vio- | |

[pagina 22]

| |

lent than this pastoral one. Though the peoples of New France are portrayed in almost entirely peaceful terms, human sacrifice appears in the images of ‘Mexicans’ (Aztecs). Still, given the repertory of horrific and often cannibalistic images available to Picart, he clearly chose to tone down the violence, and when he depicts human sacrifice, it is almost invariably a priest who does the deed.Ga naar eindnoot39 He shows natives before going into battle or mourning their losses afterward; he does not depict them in combat. He refers to the sacrifice of the first born among the ‘Floridians’, but he chooses to focus on the moments of ritual dancing beforehand, not the deed itself.Ga naar eindnoot40 Picart worked from a model, like that in Lahontan, when he had one to hand, but he picked his models carefully. The only engraving on Islam that he drew himself (he died while the volume was in preparation) is the double plate engraving of dancing dervishes [Figure 6] that he copied from an engraving published in 1715. The plate had been added in 1715 to a collection of 100 engravings about Islam first published in Paris the year before. The original engravings had been made after paintings by the Flemish artist Jean-Baptiste Vanmour that had been commissioned by the French ambassador to the Ottoman Turks from 1699 to 1710, Marquis Charles de Ferriol. Picart changed the title of this engraving, which in the original read ‘The Dervishes in their Temple at Pera [a district of Istanbul], having just finished whirling’, to the more generic, ‘Dance of the Dervishes’.Ga naar eindnoot41 His aim was to generalize as much as possible; he wanted to draw attention to dervishes as a type and not just to a specific groups of dervishes in one place and time. Picart's choice of this engraving showed much more respect for Islam and especially for Sufism than was common in Europe at the time. Europeans were fascinated by whirling and howling dervishes, but most commentators focused on their supposed libertinism, considering them immoral, drunk, and frenetic.Ga naar eindnoot42 Picart's choice of engraving demonstrates his desire to take Sufism seriously. The dervishes are dancing, and their faces exhibit trance-like features, but nothing about them is frenzied or bacchanalian. The mysticism of the Sufis, moreover, required no high priest or church. From Picart's personal library, it is possible to infer that he had a serious interest in Islam, for he owned a 1649 edition of the first translation of the Koran into French by André du Ryer, Ludovico Marracci's 1698 Latin translation of the Koran, and a 1717 Latin edition of Adriaan Reland's groundbreaking work on Islam (first published in 1705). Reland was a professor of Oriental languages at Utrecht University and one of the first European scholars to write about Islam in an objective manner. Bernard reproduced large sections of Reland's book in the text of the volume on Islam. Picart prepared the vignette for the title page of the 1721 French translation of Reland's work.Ga naar eindnoot43 Picart also owned a copy of Guillaume Postel's De cosmographica disciplina et signorum coelestium [Cosmography and Celestial Signs], which tried to incorporate Arabic astrology and Greek hermetic philosophy into a universal religion. Did Picart share Postel's heretical dream of a reconciliation of Christianity and Islam? Had he read François Bernier's published letter of 1688 comparing Sufism and Quietism, a | |

[pagina 23]

| |

mystical version of Catholicism found in France? Was Picart looking for some kind of universal syncretic religion? Such questions cannot be answered definitively on the basis of the evidence available, but his choice of images and selection of books in his library are certainly suggestive. At the very least, it is indisputable that Picart wanted to show that Islam could be fruitfully compared to other religions. The engravings in the volume on Islam demonstrate that Muslims too had marriage and death ceremonies, ritual clothing, festivals and carnivals, and even ‘temples’ such as the Grand Mosque at Mecca.Ga naar eindnoot44 Although Europeans had begun to consider a less disparaging view of Muhammad and Islam, Picart definitely took his distance from much of the scholarship of the time. Marracci explicitly produced his new Latin translation of the Koran in order to refute it. The English translator of Reland's more sympathetic account of Islam claimed that his only interest was to ‘expose this Deceiver, and his Reveries, to the Laughter and Contempt of all the sensible part of Mankind’.Ga naar eindnoot45 When George Sale produced an English translation of the Koran in 1734 (the year after Picart's death), he granted that Muhammad could not be considered equal to Moses or Jesus because their ‘laws came really from heaven’. Muhammad gave his people ‘the best religion he could, as well as the best laws, preferable, at least, to those of the ancient pagan lawgivers’.Ga naar eindnoot46 Picart had no interest in exposing Islam ‘to the Laughter and Contempt’ of mankind, quite the contrary. Portraying religious practices outside of Christianity with respect and even a certain amount of sympathy was essential to the deeper purposes of the grand endeavor of Bernard and Picart. They wanted readers and viewers to grasp the commonalities of religious ceremonies and customs across the globe. The use of generic titles for images made this clear: everyone had marriages and death rituals, and most cultures had festivals, processions, ritual instruments, and temples. The commonalities established the category of religion as something that could be observed across cultures. Bernard defined the object quite clearly in his opening pages: [A]ll men together, however extravagant they are in their worship, always have in mind a Being or Beings that they fear or respect and which are consequently above them. Whether these Beings are called Gods, Demons, Spirits, etc. it remains certain that they are regarded as very powerful since they are respectfully accorded what all peoples concur in calling religious worship.Ga naar eindnoot47 For the 1720s, indeed even for the 1820s, this was a remarkably forthright conception of religion as a culturally relative category. Underlying the emphasis on commonality, however, was a Protestant and perhaps even deistic critique of excessive ceremonialism. Bernard and Picart seemed to prefer the ‘customs’ of their title to the ‘ceremonies’.Ga naar eindnoot48 They took Catholic ceremonies, in particular, as a special target. Yet Picart did not render the Catholic ceremonies in | |

[pagina 24]

| |

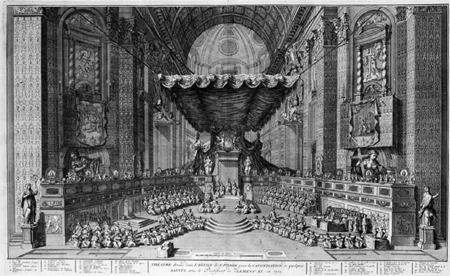

volumes one and two pictorially ridiculous; he took them, after all, from Catholic sources. His visual criticism is more subtle and relies on the process of comparison that De Piles had attributed to engraving more generally. Those comparisons could not be established literally side by side, as each religion was treated separately. Still, viewers would no doubt have been especially struck by the double page folio engravings, which form a kind of running thread of the work. There are 31 of them dispersed over seven volumes. Two very different ones show how the process of comparison could work to make Catholicism seem like ‘idolatrous’ religious practices [Figures 7 and 8].  Figure 7: The The Ceremonial Stage of St. Peter's 1712, volume 1 second part, Picard and Bernard's Cérémonies et coutumes.

Following his usual practice of seeking the most authentic models, Picart took the ceremonial staging of St. Peter's for the canonization of four saints on May 12, 1712 [Figure 7] from an impeccable Catholic source, an etching drawn by Pietro Ostini and engraved by Federico Mastrozzi, perhaps at the behest of Pope Clement XI himself, a noted patron of the arts.Ga naar eindnoot49 Only when viewed side by side with another double plate engraving of a very different religious practice [Figure 8] do the elements of possible comparison emerge. Picart's double plate engraving of the Temple of 1,000 Idols (the temple of Sanjūsangen-dō in Kyoto still stands today) is based on a print in Arnoldus Montanus's collection of voyages to Japan that was first published in Dutch in 1669.Ga naar eindnoot50 In this case, Picart did not simply copy his predecessor. He changed the placement of the human figures and added to them in order to create a greater sense of vivacity, and | |

[pagina 25]

| |

he filled out the shadowy sculptural reliefs on the top tier in Montanus's version with much scarier half-human, half animal figures.  Figure 8: The Temple of 1000 Idols in Japan (1726), volume 4 of Picard and Bernard's Cérémonies et coutumes.

Some viewers now would see in this last image an example of European ‘orientalizing’ of unfamiliar religions, especially with the rather riotous pseudo-statues found in front of the god identified in the text as Amida (now known as one of many incarnations of the Buddha). Picart was following Montanus in his renditions of these figures. When compared to the image of the canonization ceremony, moreover, the techniques are not all that different. In the canonization ceremony, many of the statues in niches in the wall seem strangely lifelike too (they are that way in the Mastrozzi original), and more important still, the human figures in the Catholic ceremony are completely dwarfed by the ceremonial décor, whereas in the Japanese temple, the ‘idols’, representations of Canon [Kannon], the son of Amida, according to the text, are lifelike and similar in size to the humans in the scene. In fact, the ordinary worshippers in the Japanese temple are much more natural and interesting than the clerics at the canonization ceremony. At the canonization ceremony, the church interior overwhelms the humans participating in the ritual. The humans do not seem like agents, unlike the people in the Japanese scene. The implications of the comparison are subtle but unmistakable. Religions, as they become more invested in priests, churches, and ceremonies, threaten to erase their | |

[pagina 26]

| |

original human elements. The size of the prints - each consists of two folio pages - underlines the point of the exercise. Bigness, that is, big buildings with large architectural volumes, distances humans from their internal emotions and their capacity to share (as in the Passover seder) and to celebrate their human qualities together (as in the Canadian marriage). Worst of all are the Catholics, in particular the high priesthood of the Roman church. Although every known religion, including Judaism, had a tendency to degenerate into empty ceremonialism, according to Bernard's text, Catholics seem to have pushed this ritualism furthest. The supposedly familiar - Catholicism - has been rendered strange, like pagan idolatry. The supposedly strange - Japanese Buddhism, we would call it - seems not so strange after all.Ga naar eindnoot51 The Japanese are dressed differently but their actions are recognizable; a father walks with his son, porters carry incense, some men talk together while others bow reverently. The gods may be strange, but the people in the temple are not. With their explicit and implicit forms of comparison, the images in Cérémonies et coutumes make the category religion visible to any viewer. To some extent, then, the images do externalize religion and make it a category of understanding like politics, society, and culture. But they also create new kinds of identification with religious practices previously considered pagan, heretical, barbarous, and scandalous. The viewer can imagine being there, not necessarily as a Canadian about to marry or a cardinal about to witness a canonization but as an observer of the ceremony. The disposition of the images puts the viewer right outside the scene; the viewer is invited to identify. Both these processes - externalization and internalization or identification - were vital elements in developing a new attitude toward religion. They did not necessarily entail disengagement from religion in the form of indifference, deism, or atheism, though they could have those consequences for some people. Picart himself appeared more interested in finding universal qualities in religion and in seeking a more interior form of religiosity than he did in distancing himself from religion altogether. The obvious aesthetic effort he put into certain engravings demonstrates his deep interest in religious experience. One book, even one with 250 plates of all the known religions of the world, did not bring about religious tolerance or freedom of religion. These goals have yet to be completely attained, even in our own time. One book can nonetheless exemplify the process by which a shift in world view took place in the eighteenth century. Europeans and Euro-Americans had to be able to envision and to some extent identify with other religious practices, if they were to get any distance on their own. Enlightenment figures such as Locke, Bayle and Voltaire helped to set the process in motion by raising questions about the validity of intolerance. Books such as Cérémonies et coutumes invited readers and viewers to broaden their horizons, consider the inner logic of other peoples' beliefs, and thereby reassess the place of their own creeds. It was a long leap from the 1720s to 1789 and the first formulations of freedom of religion, and there are | |

[pagina 27]

| |

still many stories to be told about that development. Picart's images made viewers stop and wonder and, in some cases, think, and that inspired some of them to take steps along the path of accepting religious difference and imagining that religion could be a choice, rather than a given. The place of religion, and therefore of religious tolerance and freedom, was not just a question of belief or organized systems of thought. It was also a matter of vision, envisioning, and insight. |

|