Burgerhartlezing 2010. Global Equality and Inequality in Enlightenment Thought

(2010)–Siep Stuurman, [tijdschrift] Burgerhartlezing, [tijdschrift] Documentatieblad werkgroep Achttiende eeuw–

[pagina 7]

| |

Global Equality and Inequality in Enlightenment ThoughtGa naar eindnoot+

| |

[pagina 8]

| |

preliminary discourse of the Encyclopédie, d'Alembert wrote to Madame du Deffand, ‘I had posterity before my eyes at every line’.Ga naar eindnoot2 But how does our intellectual culture relate to the Enlightenment? At the present time, there are two major currents of thought and opinion that pretend to have the answer. In the dominant canon of history and politics in the West, the Enlightenment is depicted as the historical moment that laid the groundwork for today's hegemonic global culture of liberal democracy and human rights. Following the lead of Francis Fukuyama, many pundits have celebrated the final victory of those ideals, especially after the rise of Islamic Fundamentalism and the fall of the Berlin Wall. Others however, the postmodernists for short, have criticized the Enlightenment, arguing that the philosophical machinery of Enlightenment creates its own reality, reconfiguring human plurality in the homogenizing mold of universal reason. According to the postmodern critics, the Enlightenment tenet of improving the human condition according to a rational design led to the colonial project of a ‘civilizing mission’, and finally to the ghastly utopianisms of the totalitarian ideologies of the twentieth century. I will argue that both the liberal celebration and the postmodern critique of the Enlightenment are misguided. The historical evidence, I will show, offers us a richer, more ambiguous and less unified picture. The men and women of the eighteenth century were not the belated theorists of a well-defined modern world. They tried to make sense of the convulsions and birth-pangs of a modernity they only partly understood. The Enlightenment was not an ideology of modernity, but an ever ongoing series of debates, controversies and reappraisals.Ga naar eindnoot3 Probably the only feature of Enlightenment culture all its historians agree upon is a certain open-mindedness, often characterized as an offspring of the Cartesian autonomy of the mind or simply as esprit de critique.Ga naar eindnoot4 The heart of Enlightenment culture was a critical mentality rather than a catalogue of canonical ideas. As Georges Minois observes in his history of Ancien Régime censorship, you can censor specific, well-defined ideas, but you cannot censor a mentality.Ga naar eindnoot5 The Enlightenment was hard to pin down, not only for early-modern censors, but for latter-day historians as well. The Enlightenment is thus best seen as an ongoing series of debates. We should not, however, too readily equate disagreements and inconsistencies with weakness. The kaleidoscopic versatility of the esprit de critique also accounts for its remarkable staying power. | |

Enlightenment, Modernity and EqualityOur problem can be attacked from many different angles. Today, I will focus on the subject of global equality and inequality. This problem is well suited to review our relationship to the intellectual legacies of the Enlightenment. It divided eighteenth-century philosophers as much as present-day commentators. According to the postmodern critique, the universalistic claims of Enlightenment human science gave rise to a domineering mono-cultural worldview that eventually spawned the civilizing | |

[pagina 9]

| |

mission of the European colonial powers. This worldview admitted the ‘natural equality’ of all human beings on earth, but on those who were already ‘enlightened’ it bestowed a global pedagogical authority over those who had not yet seen the light. In the harsh realities of history, the equality of non-Europeans took the shape of a receding target, an everlasting ‘not yet’. Underpinning the vindication of pedagogical reason was a historical vision of European, or Western, civilization as the culminating stage of world history. The script for the future history of the rest of the world was already written in Europe.Ga naar eindnoot6 For today's liberal champions of ‘Enlightenment values’ the case is equally straightforward. In their opinion, a good society can only be erected on the foundations of the core values of liberty and equality. The Enlightenment being the repository of those values, it provides the indispensible moral and intellectual foundations of our liberal-democratic civilization, and has to be defended unreservedly. It follows that the adherents of ‘other cultures’ cannot claim full equality in today's global West, unless they agree to become ‘enlightened’, as a rule under the guidance of those who already are. Global enlightenment, the liberal defenders of the Enlightenment contend, is not only desirable but also unavoidable given the main trend of modern history, which they theorize as the emancipation and secularization of human individuals on an ever-increasing scale. In their view, that is the core of modernity. It is obvious that the two visions briefly outlined above are closely related and partly overlapping. The post-modern critique appears to acknowledge the Enlightenment values of liberty and equality; for otherwise it is hard to see on what moral or political grounds it can condemn colonialism or Western arrogance. On the other hand, the liberal celebration of the emancipation of humanity is wedded to a view of history that is hard to tell apart from the philosophy of history the postmodern critique depicts as the hard core of the Enlightenment's brief for global inequality. The two visions thus seem to share a basic model of temporality, even though it would be a rash overstatement to say that their discourses of time and history are identical. | |

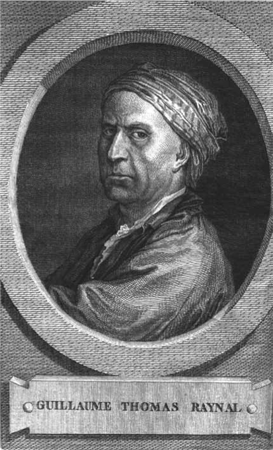

Enlightenment and EmpireWorld history is the history of the rise and fall of empires. That was true in antiquity, it was equally true in early-modern times, and it still holds true today. To inquire into the world-historical import of ideas is to examine their narratives, explanations and judgments of the empires of their times. This is a feasible enterprise thanks to the work of those historians and philosophers who have begun to recover a significant anti-imperialist strand in the thought of the eighteenth century. This is very much an ongoing and unfinished line of research. To give one, but very significant, example: the most impressive monument of the anti-imperialist turn is probably the Histoire des Deux Indes (1770, 1780), published under the name of Guillaume Thomas Raynal (the ‘Abbé Raynal’), but actually coauthored by Denis Diderot, who also presented his own anti-imperialist argument in the Supplément au voyage de Bougainville. Raynal's | |

[pagina 10]

| |

Histoire des Deux Indes (of which more below) was one of great European bestsellers of the late eighteenth century, but by the mid-nineteenth century it had fallen into oblivion. While one can buy pocket editions of Rousseau, Montesquieu or Diderot in every provincial bookshop in France, Raynal's work is difficult to locate, and it is only now, at the beginning of the twenty-first century, that a critical edition of the Histoire des Deux Indes is being published in Britain. That is remarkable, for if one wants to examine the late Enlightenment's views of the rise of European global power, Raynal is probably the best place to begin. Other important representatives of this cosmopolitan and anti-imperialist moment were the ethnologists of religious life Bernard Picart and Jean Frederic Bernard, and the philologist Abraham-Hyacinthe Anquetil-Duperron. Their writings, like Raynal's, are only available in academic libraries. The first major monograph on Picart and Bernard, by Lynn Hunt, Margaret Jacob and Wijnand Mijnhardt, was published in 2010.Ga naar eindnoot7 Likewise, there is no modern reprint of Anquetil Duperron's 1778 critique of European colonialism in India.Ga naar eindnoot8 Immanuel Kant, Johann Gottfried Herder, Edmund Burke and others also contributed to the anti-imperialist strand in Enlightenment thought, but studies focusing on that aspect of their ideas are few and far between.Ga naar eindnoot9  Jacobus van der Schley, Bernard Picart, in: Impostures innocentes, Amsterdam 1734.

The thought of these men does not fit into the rather complacent view of European progress and superiority vaunted by the likes of Adam Smith, Anne-Robert Turgot, and William Robertson. But neither does it make a clean break with their vision of historical progression and European advancement. The critics of imperialism as well as the apologists of a civilizing mission believed that Europe was passing through a transition of | |

[pagina 11]

| |

world-historical consequence that would determine the future trajectory of the rest of the globe. The critics of imperialism championed the equal dignity and rights of all human beings on the planet earth. We may summarize their ideal as global cross-cultural equality. But other important thinkers fundamentally disagreed or simply ignored the critique. The upshot is that the question, ‘did the Enlightenment advocate global equality?’ cannot be answered one way or another. Likewise, there is deep disagreement about the moral evaluation of European and worldwide ‘progress’. That much is clear. For all that, there seems to be a modicum of agreement on the direction of historical change. It is there that I propose to begin my discussion. | |

The Arrow of TimeIt is well known that not all Enlightenment thinkers subscribed to an optimistic view of modern history as blissful progress. Voltaire's Candide (1759) and Rousseau's Discours sur les sciences et les arts (1751) suffice to make the point. The immediate occasion for drafting Candide was the 1755 Lisbon earthquake, in which more than ten thousand people perished. This apparently senseless disaster occasioned widespread questioning of the belief in the guiding hand of divine providence in human history. As Voltaire exclaimed in his famous poem about the earthquake: Lisbonne, qui n'est plus, eut-elle plus de vices

Que Londres, que Paris, plongés dans les délices?

Lisbonne est abimée, et l'on danse à Paris.Ga naar eindnoot10

Others, however, would not so lightly abandon their faith in providence. At the very end of the century Thomas Robert Malthus flatly affirmed that nature's hardships were meant to incite humanity to greater industry and inventiveness. In this way, argued Malthus, ‘the gracious designs of Providence’ resulted in an increase of humanity's productive powers.Ga naar eindnoot11 The very same natural catastrophes could thus induce some to pessimism and others to optimism. We may assume that Voltaire, too, thought humanity capable of much ingenuity and industry, but for him the human costs were too high to warrant a complacent belief in divine benevolence. At a deeper level of self-questioning Rousseau wondered what all this industry and ingenuity was good for when it only incited humanity to persevere in its course of folly and delusion. All of this is well known. What is not always noticed, however, is how much the historical views of the ‘optimists’ and the ‘pessimists’ had in common. Juxtaposing, for instance, Jean-Jacques Rousseau and Adam Smith, who were contemporaries, it is obvious that they arrived at contrary appraisals of European civilization. Where Smith saw a gradual process of civil and material improvement, Rousseau was struck by the unstoppable advance of corruption, oppression and moral indifference. While Smith confidently asserted that a frugal European peasant enjoyed more material comfort than ‘many an African king, the absolute master of the lives and liberties of ten thou- | |

[pagina 12]

| |

sand naked savages’, Rousseau viewed the dissemination of European culture in the rest of the world with deep suspicion and dark foreboding. To him, the increase of knowledge and material comfort were but ‘the garlands of flowers adorning the iron chains’ of humanity.Ga naar eindnoot12 But their well-known fundamental discord easily hides from view what they have in common. Rousseau certainly did not believe in moral progress, but he shared with Smith a basic notion of historical time as development. Likewise, both men accepted the irreversibility of history and Rousseau knew as well as Smith that a ‘return to nature’ was beyond the reach of the civilized people of the eighteenth century. Responding to Voltaire's critique of the Discours sur l'inégalité, Rousseau clung to his conviction that all of human progression (‘tous les progrès humains’) is pernicious to the species, and that the advancement of knowledge and the mind, augmenting our pride and multiplying our derangements (‘égarements’), soon accelerates our misfortunes. However, he continues, we have now entered an epoch when the evil is of such a magnitude that its further increase can only be halted by a recourse to the very causes that brought it about. When I had followed my pristine vocation and had never read or written, I would undoubtedly be a happier man, laments Rousseau. But as things now stand, he concludes, ‘the annihilation of Letters would deprive me of the sole pleasure that is left’.Ga naar eindnoot13 Translated into our terms, Rousseau concludes that only modern remedies can cure the ills of modernity. Just like Adam Smith and the other thinkers of the Scottish Enlightenment, Rousseau conceives of humans as inventive and innovating beings. In contrast to the communication of animals, he observes, human languages are not instinctual but conventional: ‘Voila pourquoi l'homme fait des progrès soit en bien soit en mal, et pourquoi les animaux n'en font point.’Ga naar eindnoot14 Like the Scots, Rousseau discerns several stages in the evolution of humanity: first come the ‘savages’ who are hunters, then the ‘barbarians’ who are pastoral nomads, and finally the ‘civilized men’ who are tillers of the soil.Ga naar eindnoot15 While Rousseau disagrees with most of his contemporaries about the moral evaluation of human progress, he shares the temporal framework underpinning their visions of the history of humanity in a world-historical perspective that is of capital importance. In Enlightenment developmental time, all peoples are destined to progress along the same path. In a less elaborated fashion, the point was already made by seventeenth-century philosophers of natural law, such as Samuel Pufendorf and John Locke, as well as by a host of other thinkers, among them the Cartesian François Poulain de la Barre and the Gassendist François Bernier.Ga naar eindnoot16 All of them assumed that the ‘American savages’ represented the dawn of humanity. In the eighteenth century, this view of history was couched in the widely held four-stage theory of world history. As Adam Smith tersely summarized it in his Glasgow lectures on jurisprudence (1752-1764): ‘The four stages of society are hunting, pasturage, farming, and commerce.’Ga naar eindnoot17 According to the four-stages theory, the Americans were still in the first stage, the no- | |

[pagina 13]

| |

madic peoples of the Eurasian steppe dwelt in the second stage, the great civilizations from Egypt and Rome to Iran, India, China and Japan had reached the third stage, but only eighteenth-century Europe had entered the fourth and final stage, usually named ‘commercial society’. This grand vista of the evolution of humanity, known as histoire philosophique in the francophone Republic of Letters and as conjectural history in Britain, provided the temporal frame for virtually all Enlightenment thinking about history and social development. Time was identified with progression and development.Ga naar eindnoot18 The catch in this theory of historical progression was let out of the bag by Bernard le Bovier de Fontenelle, one of the emblematic figures of the early French Enlightenment. It was Fontenelle who coined the expression ‘progrès de l'esprit humain’, a key concept underpinning all later Enlightenment philosophies of history.Ga naar eindnoot19 In De l'origine des fables (drafted 1691-99, published 1724) he declares that there is ‘an astonishing conformity between the myths of the Americans and those of the Greeks’. All peoples begin their historical career with myths, and the early Greeks had been ‘savages’ just as the ‘American savages’ in Fontenelle's day. He concludes ‘that the Americans would finally have come to think as rationally as the Greeks, if they had been left the time [“loisir”]’.Ga naar eindnoot20 And there is the catch, for the Americans were deprived of their ‘time’ in the most literal sense. The European conquest obliterated the future of their present, and identified their present itself with the distant past of the European future. Later on, even the American present would be downgraded. According to the Scottish historian William Robertson, whose highly influential History of America was published shortly after Smith's Wealth of Nations, the greater part of the American lands ‘were almost in the same state as if they had been without inhabitants’.Ga naar eindnoot21 Even Mexico and Peru, he observed, hardly merited ‘the name of civilized’.Ga naar eindnoot22 America had a future, but the Americans had not. Economically considered, America was terra nullius, a vast expanse of uncultivated soil, ready to be appropriated by enterprising Europeans. Two centuries before, José de Acosta, whose Historia Natural y Moral de las Indias (1590) was the result of fifteen years of observation in Peru, had marveled at the grand causeways and the countless cities of the Inca, but Robertson declared that apart from Cuzco there were only villages and isolated hamlets in Peru.Ga naar eindnoot23 Acosta's work, soon translated into Italian, French, German, English, Dutch and Latin, was probably the most influential handbook about America in de seventeenth century, but in the next century a new, secular vision of America replaced Acosta's providential explication of sacred history with the four-stage philosophy of history. Some authors, most notoriously Cornelius de Pauw, even maintained that the animals and people of America were caught in an ongoing process of degeneration. Robertson, like Buffon, did not go quite as far as that, but neither did he envisage a meaningful role for the native Americans in the future trajectory of humanity. In the temporality of histoire philosophique, the Americans still existed in geographical space, but philosophically speaking their time was over. As in America, so in many other parts | |

[pagina 14]

| |

of the world. In this way, Enlightenment conjectural history paved the way for the nineteenth-century theories that presented the ‘primitive races’ with the choice between ‘civilizing’ themselves out of existence or to suffer the cruel fate of extinction.Ga naar eindnoot24 | |

Enlightenment Critiques of European ImperialismEven so, the Enlightenment spawned powerful critiques of imperialism. We should not fall prey to the facile belief that all the philosophers of the eighteenth century Enlightenment fully endorsed the European conquest of the globe. The picture that has emerged over the last decades is more complicated than that. Several early-modern intellectual trends contributed to a less sanguine view of European advancement as well a greater appreciation of the importance of other, in particular Asian, civilizations to world history. The first point to note is the emergence of challenges to the Eurocentric view of history. Since the sixteenth century, most literate Europeans knew that the entire world was habitable, and that Europe contained only a small part of the world's population.Ga naar eindnoot25 Admittedly, many Europeans were more interested in power and profit than in knowledge of the non-European world for its own sake.Ga naar eindnoot26 Such instrumental Eurocentrism did not disappear in the eighteenth century, but it now coexisted with a growing awareness that world history transcended the traditional canon of Judaea, Greece and Rome. Less than half of the seventeenth-century ‘universal histories’ discussed China, but the great majority of eighteenth-century world histories included it, even though many still sought to comprehend the new global history within a biblical framework.Ga naar eindnoot27 Voltaire's Essai sur les Moeurs gave pride of place to European history, but its message was that one had to acquire some grasp of world history to understand what Europe had become and where it was going. Voltaire made fun of historians who pretended to write ‘universal history’, but who mostly copied one another while being completely ignorant of the history of three-quarters of the globe.Ga naar eindnoot28 Admittedly, Voltaire's view of world history was marred by his anti-Judaism, but his affirmation of a universal morality went beyond such narrow visions: ‘Les rites établis divisent aujourd'hui le genre humain, et la morale le réunit’.Ga naar eindnoot29 The Essai seeks to combat a vulgar Eurocentrism it assumes in its readers. The true lesson of world history, Voltaire intimates, is universal toleration.Ga naar eindnoot30 The three elements that explain the course of world history, he concludes, are climate, political regimes and religion. All religions contain numerous absurdities (‘sottises’), but their moral precepts are everywhere the same: ‘Soyez équitables et bienfaisants.’Ga naar eindnoot31 Religion is thus a countervailing power to the universal ‘esprit de guerre, de meutre et de destruction’ that has reigned in Europe and the Orient alike. Beyond that, however, Voltaire noted major differences between Europe and the Orient. In Europe, government is less despotic and its arts and sciences are in the process of surpassing those of Asia.Ga naar eindnoot32 Finally, the greatest difference between East and West concerns the position of women. They are more esteemed in Europe than in the Orient, even though Voltaire disputes the (fairly com- | |

[pagina 15]

| |

mon) view that identifies Oriental matrimony with female slavery.Ga naar eindnoot33 Karen O'Brien has observed that Voltaire's account of non-Western civilizations are ‘appreciative but not fully developmental’.Ga naar eindnoot34 That seems a reasonable verdict. Toleration and a rational approach to religious difference was also the message of the massive, seven-volume Cérémonies et coutumes réligieuses de tous les peuples du monde, published by Bernard Picart and Jean Frederic Bernard from 1723 to 1737, and translated and reprinted throughout the eighteenth century. It was the first encyclopedic treatment of all the major religions of the world that was not dominated by Christian apologetics, although the Protestant background of the authors informed their narrative in many places.Ga naar eindnoot35 Their fairly neutral and open-minded discussion of the world's religions marked the emergence of a new subject, the comparative study of religion. Other religions were simply other religions: different, but not necessarily pernicious, ‘pagan’ or satanically inspired. According to Hunt, Jacob and Mijnhardt, the Cérémonies discuss ‘idolatry’ as a phenomenon found in virtually all religions (except Protestantism), and they are more interested in analysis and comparison than in condemnation. Likewise, ‘Bernard and Picart exhibit little interest in aligning peoples along a spectrum running from primitive to civilized. They find civility, modesty, and politeness in virtually all cultures’.  Bernard Picart, Ixora, Divinité des Indes Orientales, 1722, in: Cérémonies et Coutumes réligieuses des Peuples idolâtres.

| |

[pagina 16]

| |

Generally, Bernard and Picart ‘are more concerned with the similarities between peoples than with their differences’.Ga naar eindnoot36 In the section on China, they underline the common elements found in all creeds: ‘All religions resemble each other in something. It is this resemblance that encourages minds of a certain boldness to risk the establishment of a project of universal syncretism. How beautiful it would be to arrive at that point and to be able to make people with an overly opinionated character understand that with the help of charity one finds everywhere brothers’.Ga naar eindnoot37 Bernard and Picart's universal syncretism seems to be based on the conviction that the existence of one God or divine principle could be expressed in the languages of different religions. The emphasis on universal brotherhood provides a counterpoint to European arrogance and the alleged Christian monopoly of truth. One encounters a similar approach to cultural difference in the writings of Abraham-Hyacinthe Anquetil Duperron, one of the pioneers of Oriental philology, who spent seven years in India to collect and translate the ancient Persian Zoroastrian sacred books. During his travels Anquetil developed a measure of respect for Indian civilization and a hearty aversion to European arrogance and greed. On his passage to India, he was shocked to discover that many men on his ship were released criminals, on their way to become proud colonists. But what struck him most of all was the enormity of European ignorance. To put things right, Anquetil proposed a global traveling academy, whose members should collect first-hand knowledge of the languages, religions and customs of peoples all over the world.Ga naar eindnoot38 In his Législation Orientale (1778), Anquetil vehemently criticizes the theory of ‘Oriental Despotism’ found in François Bernier's 1671 travelogue on Mughal India and popularized by Montesquieu's Esprit des Lois. Citing Mughal legal documents, he demonstrates that private property is respected in India. Anquetil regards the theory of Oriental Despotism as a thinly veiled apology for European conquest and land-grabbing in Asia. The argument of Législation orientale proceeds along two theoretically distinct lines, the first anthropological and historicist, the second moral and universal. The first line of argumentation exhorts the Europeans to consider ‘that every people, even if it differs from us, can have a real value, and reasonable laws, customs and opinions’.Ga naar eindnoot39 If one would take into account the mentality of peoples, the state of human knowledge and the nature of climate in the seventh century, Anquetil contends, one would perhaps come to see in Muhammad something else than a fanatical impostor.Ga naar eindnoot40 The second line of argument admonishes the Europeans to recognize the common humanity of all the peoples and nations in the world. Most Europeans, Anquetil avers, seem to think that people of different color and customs are inferior and can be mistreated with impunity. They do not consider that beneath the varieties of skin color there is a uniform human nature. Anquetil concludes that all peoples have the same basic needs and faculties, and consequently deserve the amity and respect of all decent men. Regrettably, he notes, the practice of the European colonists permanently violates this | |

[pagina 17]

| |

universal right. Their conquests and, most horrendous of all, the slave trade, fly in the face of ‘the inalienable rights of humanity’. Consequently, Anquetil rejected territorial colonies. India, he asserted, is already inhabited, so that there can be no right to occupy parts of it without formal concession of its proprietors, the native peoples and their rulers. The only type of colonies that might be useful to both Indians and Europeans are ‘simple commercial establishments’.Ga naar eindnoot41 Interestingly, Anquetil's critique of imperialism is not confined to a defense of the Asian high civilizations against European encroachments. In the 1770s he began to work on a massive treatise in defense of the Arctic peoples of America and Eurasia, reacting to Cornelius de Pauw's Recherches philosophiques sur les Américains (1769), which represented the native Americans as an inferior and degenerate division of humanity, as well as to Buffon's partial critique of De Pauw, where Buffon rejected the thesis that all Americans were degenerates but maintained his disdain for the Arctic ‘savages’.Ga naar eindnoot42 The greater part of Anquetil's Considérations philosophiques, historiques et géographiques sur les deux mondes, which was ready for publication in 1799 but never saw print, is devoted to a comparison between Siberia, Alaska and northern Canada. He concludes that the way of life, technology, and beliefs of the Arctic peoples of America and Eurasia a roughly similar. It follows that the inhabitants of these northern lands have developed analogous means to cope with the harsh climate. Cultural diffusion has further contributed to this outcome. Anquetil reports that Russian ethnographers think it highly probable that there was early communication between Siberia and Alaska.Ga naar eindnoot43 Anquetil concludes that the alleged ‘racial’ traits of the Arctic peoples are actually the result of a long process of successful adaptation to their environment. Among his examples are the Eskimo, whom most Europeans considered almost subhuman. Diderot's Encyclopédie depicts them as ‘the savages among the savages’ and as ‘veritable man-eaters’.Ga naar eindnoot44 European travelers, Anquetil relates, dwell on the primitive customs of the Eskimo, but they fail to notice that three quarters of the inhabitants of Europe live in equally miserable circumstances. Most travelers unthinkingly apply the yardstick of their own comfortable milieu to the rest of humanity. They do not appreciate that the Eskimo have developed the skills to navigate the stormy Arctic seas and to hunt seals and whales. In reality they possess great ingenuity, as evidenced by their invention of wooden snow goggles, a device also seen in northern Siberia but never yet invented in the deserts of Arabia. Anquetil remarks in passing that such goggles would be very useful to the French soldiers in the blinding glare of the Egyptian desert.Ga naar eindnoot45 Again and again, Anquetil reverses the usual perspective that considers the sedentary as normal and the nomadic as deviant. Much of what appears primitive to the average European is perfectly appropriate, and often more effective, in the arctic environment. Likewise, the reluctance of the northerners to engage in commerce on the unequal terms offered by the Europeans is eminently rational, though many travelers have reported it as further evidence of their ‘ferocity’. The assertion that the harsh environment explains the way of life of the arctic peoples can, of course, be read as | |

[pagina 18]

| |

exculpatory: in such circumstances they cannot help being ‘savage’. But Anquetil goes beyond that, for he affirms that the northerners can live a satisfying and happy life. That Europeans call them ‘miserable’ only reveals their own parochial outlook. In reality, peoples like the Icelanders and the Lapplanders like their own country the best. The Tungusians greatly prefer their native ways to those of the Russians. The Kalmuks only seem ‘ugly’ according to European standards of beauty, not, of course, in their own eyes.Ga naar eindnoot46 Anquetil consistently practices an inversion of the traveler's gaze. He invites his European readers to reflect on their own ethnocentrism: they should consider that ‘every nation has its proper theogony, situating the creation, the origin of the world and the human species in its own territory’.Ga naar eindnoot47 We may conclude that the Eurocentric developmental view of Adam Smith, William Robertson, Montesquieu and numerous others was not the only global discourse circulating in the eighteenth-century public sphere. Other voices, critical of the emerging Euro-global empire, made themselves heard as well. The critics of European imperialism marshaled several arguments. One, voiced by Edmund Burke in the British debates about its incipient Indian empire, concerned the corrupting feedback of imperialism on the political culture of the metropolis. Another frequently heard argument was that, given the limited means of travel and communication, worldwide empires were ungovernable, or could only be governed despotically. Those arguments harked back to Ancient historians, such as Polybius and Herodotus, who had maintained that great power corrupts even the best rulers, condemning all grand empires to a process of moral corruption and final ruin. The rise and decline of empires throughout human history, with the fall of Rome as its most dramatic example, seemed to set the seal on all dreams of everlasting empire. The despotic nature of imperial states could also be presented as an incontrovertible truth. History offered no examples of empires with a republican or representative regime. Finally, the tenet of the ungovernability of global empires looked very convincing in an age when the running horse and the sailing ship were the fastest means of long-distance travel. Actually, the latter theme tied in with the despotism argument. When an empire is so vast that people from the towns are not able to visit the capital, Diderot asserted in his observations on Russia, it cannot be a true political society. In such cases, despotic rule is the only alternative to dissolution.Ga naar eindnoot48 The two most principled arguments against empire moved on a more philosophical and lofty plane. The first condemned European conquest and overseas rule because they violated the natural equality of human beings. This argument was often couched in the novel language of ‘universal’ or ‘inalienable’ human rights. The second, anthropological, argument questioned the ideology of European superiority that was often unthinkingly invoked to justify European rule over ‘other peoples’. Drawing on history, geography and ethnography, it posited that Europe was only one civilization amidst others, and that other ways of life might be as reasonable and valid as the Christian standards of the European home culture. In many cases, it was the combi- | |

[pagina 19]

| |

nation of universal equality and the anthropological vindication of cultural pluralism that accounted for the robustness of the anti-imperialist argument. | |

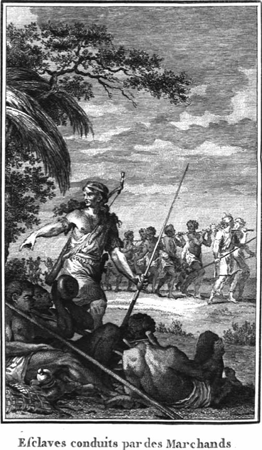

The Histoire des Deux Indes: Raynal and DiderotThe Histoire philosophique et politique des Établissemens et du Commerce des Européens dans les Deux Indes, first published in 1770, was one of great bestsellers of the late eighteenth century and a remarkable book in more than one respect. First, there was its sheer size and scope. Raynal's energy seemed endless. According to Diderot, the Abbé was ill ease when he could not hold forth on colonies, politics and commerce.Ga naar eindnoot49 In the definitive 1780 edition, the ten volumes of the Histoire des Deux Indes offered a global history of European expansion, beginning in the late fifteenth century, preceded by a world-historical prologue that went from Antiquity to modern times. Second, it comprised a history of commerce, documented with impressive statistical tables, but also philosophically celebrated as the means to the peaceful unification of the globe and an antidote to despotism and intolerance.Ga naar eindnoot50 Third, the narrative history of European expansion was consistently intertwined with a critique of European imperialism, racism and the slave trade. Finally, the concluding volume sought to assess and judge the historical consequences of the European global venture, in particular the conquest of the Americas. The grand narrative of the Histoire des Deux Indes opens with the Portuguese, Dutch, English and French exploration and colonization around the Indian Ocean. It continues with a treatment of the explorations and conquests undertaken by the Danes, Swedes, Prussians, Spaniards and Russians in the Old World. The discussion of the Russian conquest and colonization of Siberia is the longest section of this part of the work. Thereafter, Raynal proceeds to discuss the European conquest and settlement of the Americas, which fills six of his ten volumes. The American part of the Histoire follows the Spaniards from the Caribbean, to Mexico and Peru, and finally to Chile and Paraguay. Next, we encounter the Portuguese in Brazil, and the French, the English and the Dutch in the Caribbean, followed by an extensive treatment, and categorical condemnation, of the Atlantic slave trade. There, Raynal foretells the rise of a ‘new Spartacus’ who shall lead the slaves to their liberation, a passage that inspired the young Toussaint l'Ouverture who was, in 1791, to lead the successful slave revolt in the French colony of Saint Domingue (present-day Haiti). The chapter on slavery is followed by a further discussion of the activities of the Spaniards, the Dutch, the Danes, the French and the English on the islands in the American seas. The last two narrative volumes tell the story of the French and English colonization of North America. The story concludes with a glowing account of the American War of Independence and the founding of the United States of America. The final volume contains Raynal's judgment of European expansion and its feedback effects on Europe itself. Nothing on this scale had ever been attempted before. John Pocock has characterized the Histoire des Deux Indes as one of the first attempts to write the history of | |

[pagina 20]

| |

the emerging world system (the neologism ‘world system’ was coined by Immanuel Wallerstein in the 1970s).Ga naar eindnoot51 Modern historians as well as contemporaries have berated Raynal for his inconsistencies and his rhetorical exuberance. Michèle Duchet has called the Histoire des Deux Indes a polyphonic text. Others have taken Raynal to task for eclecticism or called him a miserable compilateur. I do not deny that there is something to that, and neither do I wish to rehabilitate the poor Abbé. Even so, we are justified to ask if anyone at the time could have done better. The first edition of the Histoire went to the press in 1770, six years before the Wealth of Nations; the definitive edition was published in 1780. The world market was not, at that time, an ready-made available historical concept.  Abbé Raynal, Histoire philosophique et politique des Établissemens et du Commerce des Européens dans les Deux Indes, volume I, Genève, 1781.

Comparing Raynal's treatment of it with the historical chapters of the Wealth of Nations shows parallels as well as differences, but overall Smith is no less eclectic than Raynal. Both sought to make historical sense of a new reality. Both had read their Montesquieu with its powerful notion of the doux commerce as a counterpoint to war and conquest. Raynal's explicit celebration of the civilizing impact of trade and Smith's ironic explanation of the demise of the feudal magnates make the same point. But there is a huge difference as well. Raynal's subject, the global expansion of European economic and political power, was a long-winded and tortuous historical process, in which both doux commerce and not-so-doux military power had their role to play. It was here that Raynal had his work cut out for him: how to tell a consistent story of the simultaneous and intermeshing operation of those dissimilar factors. The celebration of commerce as a peaceful world-unifying agent and the condemnation of European arrogance and arbitrary use of military power, as well as the slave trade, make an ambiguous and contradictory pair. It was a disconcerting thought that | |

[pagina 21]

| |

commerce was perhaps not uniformly beneficial. Raynal depicts commerce as a world-historical force, joining the different parts of the globe in a new web of interdependence. But from the outset he is well aware that commerce is only a part of a broader process of global exchange: The products of equatorial climates are consumed in lands near the pole; the industry of the North is transported to the South, the raiments of the Orient have become the luxuries of the Occidentals, & everywhere men (‘les hommes’) have mutually exchanged their opinions, their laws, their customs, their maladies, their remedies, their virtues & their vices.Ga naar eindnoot52  Abbé Raynal, Histoire philosophique et politique des Établissemens et du Commerce des Européens dans les Deux Indes, volume X, Genève, 1781.

| |

[pagina 22]

| |

The most obvious case of non-civilized commerce is, of course, the slave trade. But even apart from that, it was obvious that the flesh-and-blood Europeans engaging in global trade did not always bring peace and happiness to the remote coasts they visited. They also carried illnesses and vices, and the European trading companies seldom hesitated to use armed force when it served their interests. Moreover, the rapid spread of world trade called forth new desires and appetites in the peoples drawn into the new global commercial network. Beyond its purely economic consequences, commerce affected the cultural and psychological habits of Asians, Africans and Americans.

The ideal of a mutually advantageous ‘free trade’ Raynal extols with so much gusto is a theoretical model posited by political economy (a burgeoning new science in the mid-eighteenth century) rather than a historical reality. All governments in the world, European or not, adhered to the mercantilist maxim that commerce should be deployed to bolster the power of the state. Monopolies, protectionism, and other economic barriers were the rule, free trade was very much the exception. So it was in the nineteenth century, and much more so in Raynal's days.Ga naar eindnoot53 That explains why Raynal often sings the praise of commerce and the civilizing impact of European ‘reason’, but equally often compares the Europeans in Asia, Africa and America with ‘swarms of starving and cruel vultures, with as little morality and conscience as those birds of prey’.Ga naar eindnoot54 The abstraction ‘commerce’ brings peace and happiness, but over and over again the European merchants are censured for their insatiable greed. In the concluding section of his great work, Raynal looks back on the history he has written and addresses his readers in the first person: Let us pause here, & let us place ourselves in the time when America & the Indies were unknown. I address myself to the most cruel of the Europeans, & I tell him: There exist countries that will provide you with precious metals, commodious garments and delicious food. But read this history, & behold the price of their discovery. Do you want, or don't you want that discovery to be made? Can we believe that there is any creature so infernal as to answer: I WANT IT. Well! In the future, there will not be a single moment when my question shall not have the same urgency.Ga naar eindnoot55 After this rhetorical question, Raynal goes on to say that he has raised his voice for the benefit of all men without distinction, for all are equals in his eyes, as they are ‘in the eyes of the Supreme Being’. He looks forward to a future when all civilized nations (‘nations policées’) will be united by bonds of benevolence instead of exporting the example of vice and oppression to the ‘savage nations’. But the author harbors no illusions about the real answer to his rhetorical question. The concluding sentences of the book are gloomy and resigned. The time of the ‘heureuse révolution’ he has just evoked is undoubtedly far distant, Raynal declares, and his name shall be forgotten when it ever arrives. | |

[pagina 23]

| |

Let us pause in our turn at Raynal's peroration. The first point to note is that he addresses himself to the Europeans, not to the peoples oppressed by them. The second concerns the dichotomy of the ‘civilized’ and the ‘savage’ nations. The former are exhorted to bring ‘union’ and ‘benevolence’ to the latter. In Raynal's historical vision, the Europeans are the prime movers of world history. Next come the other ‘civilized’ (mostly Asian) nations who also have a role to play, even though Raynal frequently declares that their superstitious and irrational beliefs will soon be superseded by Enlightenment reason. Finally, we encounter the ‘savages’ who apparently have no agency at all. Pocock observes that the Histoire des Deux Indes denounces the Europeans ‘for their invasions and destructions of worlds not belonging to their history, but does not equip those worlds with history, or any positive agency, of their own’.Ga naar eindnoot56 Applied to the peoples of America and Africa, Pocock is mainly right, even though Raynal's call for a new Spartacus clearly evokes the possibility and the desirability of African agency. The case of Asia is still more complicated. For example, Raynal presents the arguments of the European admirers as well as the detractors of the Chinese empire, but he refrains from resolving the issue in his usual peremptory manner. Instead, he posits that European knowledge of China is not sufficient to decide the matter, and calls for fieldwork by Europeans who, having mastered the Chinese spoken and written language, must conduct their investigations among Chinese from all walks of life, in the cities as well as on the countryside.Ga naar eindnoot57 Here, his attitude is comparable to Anquetil Duperron's insistence on the enormity of European ignorance. Pocock rightly points to the absence of an autonomous history of non-European peoples in Raynal's work, but fails to note that precisely in this respect the Histoire des Deux Indes is a liminal work. It stands on the brink of, and sometimes points to, a non-Eurocentric world history. Its critique of European arrogance will have opened the mind of some of its readers, though not, perhaps, the majority. Raynal himself sponsored an essay prize contest on the question ‘Has the discovery of America been beneficial or harmful to the human race?’. Of the eight submissions that have survived, four were deeply pessimistic about the prospects of European civilization, but even these pessimists were waxing lyrically about the ‘shining exception’ of the young United States.Ga naar eindnoot58 We may conclude that the Histoire des Deux Indes did much to destroy the complacent celebration of European imperialism, but was ultimately unable to escape from the deterministic logic of the histoire philosophique its title claimed so unreservedly. | |

Diderot's Tahitian Anti-ImperialismDenis Diderot is a key figure in the Enlightenment critique of imperialism. He contributed to the Histoire des Deux Indes, he drafted or revised many of the ethnographic entries in the Encyclopédie, and finally he offered his own thoughts on European expansion and cultural difference in the Supplément au voyage de Bougainville, written in the years he collaborated with Raynal. Moreover, Jonathan Israel has recently shown | |

[pagina 24]

| |

that Diderot was in many ways the most influential thinker of the Radical Enlightenment in the third quarter of the eighteenth century.Ga naar eindnoot59 Diderot did not publish the Supplément, but its main themes are also found, though in less provocative language, in the Histoire des Deux Indes.Ga naar eindnoot60 When Diderot drafted the Supplément, his philosophy had evolved from Deism to a materialist monism. Life, including human life, he asserted, was nothing else than complex and highly organized matter. Accordingly, he maintained that human beings should follow their natural impulses and pleasures, only bridling them in order to respect the ‘natural right’ of their fellow humans to do likewise. That did not imply, however, a lifestyle of boundless gluttony and debauchery, for human happiness was best served by moderation and a measure of rational self-control. On the other hand, Diderot categorically rejected the mortification of the flesh, the vilification of physical pleasure and the double standard of Christian sexual morality. Bougainville's account of his Tahitian experiences provided him with an ideal case study to combine his anti-imperialist argument with his critique of Christian sexual morality. In the years 1766-69 the French savant and traveler Louis-Antoine de Bougainville sailed around the world. The journal of this voyage, published in 1771, contained a chapter about Tahiti, in which Bougainville described the simple and ‘natural’ way of life of the islanders, dwelling in particular on their uninhibited and ‘free’ sexual mores, including their custom of ‘offering’ their wives and daughters as sexual companions to visiting strangers. Bougainville's account of the Tahitians attracted the attention of readers all over Europe. Diderot, who himself never left Europe, used Bougainville's account as a foil for an ironic and playful philosophical argument. An exchange in the introductory section of the Supplément announces the anti-imperialist argument. When A opines that the European powers sent out only decent and benevolent men as commanders in their overseas territories, B (who speaks for Diderot) promptly retorts that he is mistaken; in reality, the European governments could not care less, an observation that parallels Anquetil Duperron's indignation about his criminal shipmates destined for a colonial career.Ga naar eindnoot61 Apart from this moral lesson, the introduction alludes to the temporality of philosophical history, explaining that the Tahitians are close to ‘the origin of the world’ while the Europeans approach its old age.Ga naar eindnoot62 Tahiti represents the first stage and Europe the final stage of the history of humanity. Then, the scene changes dramatically. We find ourselves on the shore of Tahiti. The French are about to leave. Many Tahitians are sad and tears flow copiously. But then an old man severely berates them: Weep, wretched natives of Tahiti, weep. But let it be for the coming and not the leaving of these ambitious, wicked men. One day you will know them better. One day they will come back, bearing in one hand the piece of wood you see in that man's belt, and, in the other, the sword hanging by the side of that one, to enslave you, slaughter you, or make you | |

[pagina 25]

| |

captive to their follies and vices. One day you will be subject to them, as corrupt, vile and miserable as they are.Ga naar eindnoot63 Here, the truths of philosophical history take on the hue of a prophecy of doom. The old man calls Bougainville a poisoner of nations (‘empoisonneur des nations’) and likens the French arrival among the Tahitians to an infection.Ga naar eindnoot64 Literally, his words refer to venereal diseases, but metaphorically to the introduction of European cultural practices and ideas. In language that brings to mind the biblical story of the Fall, the old man relates how the European notions of private property and sexual conquest are perverting the minds of the young Tahitians. It seems far easier to ingest European culture than to get rid of it. The other theme of the old Tahitian is to expose the hollowness of European morality. We, he says, have ‘respected our own image in you’, seeing that we are all ‘children of Nature.’ The Frenchmen, for their part, willingly accepted the gifts of the Tahitians, but when a Tahitian took some ‘miserable trinkets’ from a French ship, they cried havoc and reacted with violence. In other words, the Tahitians acknowledged the natural equality of all human beings, while the French did not. In an elegant inversion of imperialist discourse, the old man exclaims: Orou, you who understand the language of these men, tell us all, as you have told me, what they have written on that strip of metal: This land is ours. So this land is yours? Why? Because you set foot on it! If a Tahitian should one day land on your shores and engrave on one of your stones or on the bark of one of your trees, This land belongs to the people of Tahiti, what would you think then?Ga naar eindnoot65 The Europeans talk about morality, the old man intimates, but at the same time they are conspiring to steal an entire country. In the end, it is only raw power that counts. The European's global greed and land-grabbing shows them for what they really are. A large part of the Supplément is devoted to a critique of Christian sexual morality. The importance of the theme is already clear from the subtitle: ‘Sur l'inconvénient d'attacher des idées morales à certaines actions physiques qui n'en comportent pas’. The subject is discussed in a lengthy conversation between the Tahitian Orou and the chaplain of the French expedition, interrupted by the nightly seduction of the chaplain by Orou's daughter Thia. At first, the chaplain had refused the offer of sexual hospitality, and even in Thia's arms he continued to exclain ‘but my religion, but my holy orders!’. The morning after, Orou inquires into the meaning of those cries. The chaplain explains the Christian prescriptions governing sexuality and marriage. Orou objects that sexual desire is a part of human nature and cannot be erased by morality and laws. Moreover, sexual attraction is volatile and unpredictable, so that the Christian command of lifelong monogamous marriage will always founder on the rocks of human nature. Finally, the natural end of sexuality is procreation A healthy society | |

[pagina 26]

| |

welcomes children who assure the continuity of the people. Questioned by Orou, the chaplain has to admit that in practice all the Christian sexual interdictions are frequently violated in every Christian country. On the face of it, Orou seems to argue that the Tahitian morality is simply a matter of letting everyone freely follow his or her natural desires. On closer inspection, there turn out to be two ‘natural’ impulses: pleasure and procreation. The Tahitians disapprove of, and sometimes punish, sexual relationships that cannot produce offspring. In particular, old sterile women who nevertheless seek the sexual favors of men are exiled or sold into slavery. The limitations on sexual liberty and the imposition of draconian punishment on licentious old women demonstrate that the Tahitian sexual regime entails something more than freely following one's natural urges.Ga naar eindnoot66 For Diderot, culture is everywhere at work and no human society is ever ‘natural’. Even so, he is able to argue convincingly that the Tahitian code is less anti-sexual and therefore closer to ‘nature’ than the Christian one. He attributes to Orou his own maxim that it is best to judge all cultures by a common standard: You can't condemn the ways of Europe in the light of those of Tahiti, nor consequently the ways of Tahiti in the light of those of your country. We must have a more reliable standard, so what will that be? Do you know a better one than the general welfare and individual utility?Ga naar eindnoot67 The Europeans, Diderot shall finally conclude, are forced to live under three codes: Nature, Christian morality, and the Laws of the State. Since the three codes contradict one another, they are inevitably in disharmony with themselves.Ga naar eindnoot68 The solution is not, however, to transplant the Tahitian code to Europe. Instead, the Europeans should seek to reform bad laws and to weaken the hold of the Christian churches on public affairs. What is the upshot of Diderot's Tahitian argument for his view of European expansion? In the first place, he admonishes the Europeans not to measure all peoples in the world by the narrow yardstick of their own mores. Different ways of life can be imagined, and all of them have their drawbacks and strong points. In this connection, it is important to take note of Diderot's discussion of the limits of Tahitian sexual freedom. Tahiti may be closer to ‘nature’ than Christian Europe, but it is not equated to ‘nature’. What Diderot is saying is not ‘follow Tahiti’, but rather: ‘observe and seek to understand, and do not condemn unthinkingly’. His message to the Europeans, voiced by B in the concluding section of the Supplément, tells them to reform their own laws according to the maxims of the general welfare and individual utility. For Diderot, those maxims possess a universal, cross-cultural validity, but their high level of abstraction leaves ample room for different cultural elaborations. In Diderot, there is something like a universal philosophical standard, but it does not entail a universal culture. His mindset is tentative and empirical rather than deductive and apodictic. | |

[pagina 27]

| |

Elsewhere, he followed up on the dialogical cultural theory of the Supplément by envisaging the possibility of a way of life that would sagely mix ‘civilized’ and ‘savage’ elements.Ga naar eindnoot69 Even so, the philosophical conceivability of cultural variation sits ill with the prophecy of doom voiced by Diderot's Old Tahitian. The old sage expected Europe to make over the world in its own perverted image. His dark vision of the future shows that Diderot is well aware of the overwhelming force of Enlightenment developmental time, both as an intellectual idée-force and as a mobile of political and economic history. Contrary to Rousseau, Diderot identifies despotism as the main corrupting force in history, while he sees ‘industry’ and the ‘arts’ as potentially liberating forces. However, even when it comes to the arrow of time, Diderot cannot commit himself unreservedly to one view. Much of what he says is imbued with the developmental temporality of philosophical history, but he also conceives of history in terms of a ‘natural law’ that drives all human societies towards ‘despotism and dissolution’, caught in the iron cage of the eternal rise and decline of empires that no human efforts can withstand.Ga naar eindnoot70 Diderot thus invokes both the ancient Herodotean political cycle and modern developmental temporality. In the end, the contradictory trends and ideas of eighteenth-century global history remain unresolved in Diderot's labyrinthine philosophical discourse. Quite fittingly, the Supplément ends with an open question rather than an apodictic truth claim. | |

Conclusion: How to Assess the Enlightenment Critique of ImperialismWhere do we go from here? What meanings can we discover in the Enlightenment critique of European imperialism? And what is their significance, if any, to our presentday discussions of globalization and Western dominance? What is their relevance to our controversies over universalistic moral principles and the stubborn persistence of cultural difference, both outside and within the ‘West’? The first thing to notice is that history did not begin with the Enlightenment. Far more than to us, antiquity was a living presence to the men and women of the eighteenth century. Even as they were confidently going beyond its intellectual legacy, the ideas of ancient Greece and Rome were still significant and meaningful to them. It is only against the backdrop of antiquity than we can fully appreciate the novelty of Enlightenment philosophical history. To the Greek historian Herodotus, the Chinese historian Sima Qian, and the Arabic philosopher of history Ibn Khaldun, the differences between sedentary civilization and the ways of the nomadic peoples of the steppe and the desert were of great significance, but none of them looked forward to a future transition from ‘nomadism’ to ‘civilization’.Ga naar eindnoot71 The boundary zone between the two cultures constituted the Great Frontier of the old world. No one questioned its permanence. Enlightenment thinkers, however, situated the nomadic peoples not only in space but also in time. They were now designated as ‘barbarians’ dwelling in the second stage of the evolution of humanity. This vision represented a major new | |

[pagina 28]

| |

departure. I have sought to show how deeply it constrained the range of future cultural variation in Enlightenment thought, even in the case of critics of European imperialism such as Anquetil Duperron, Raynal and Diderot. Their critique often sounds like a spectral lament about the inevitable destruction of non-European cultures, as in Raynal's impotent rhetorical outcry in the final pages of the Histoire des Deux Indes. A second point concerns the modernization of inequality. Besides modern, universal equality, the Enlightenment spawned several equally modern discourses of inequality. The new science of political economy demonstrated that a certain amount of material inequality was a necessary condition of economic progress. Novel bio-psychic theories of sexual difference defined the ‘nature’ of women as complementary to male nature and contested the arguments for gender equality of other Enlightenment thinkers. The radical Enlightenment regarded human beings as the most advanced animal species and accordingly applied biological taxonomy to humans as it did to plants and animals. The result was a new science of racial classification that could be invoked to criticize those Enlightenment thinkers who advocated racial equality. Finally, numerous philosophers claimed a pedagogical authority for enlightened elites, who were called upon to educate and civilize the rest of humanity. Consequently, it would be a serious misreading of the historical record to equate Enlightenment reason, even in its radical varieties, with the discourse of modern equality. What we find in the Enlightenment is an ever-shifting balance between discourses of modern equality and modern inequality. For all that, we should not underestimate the sincerity and vigor of the anti-imperialist critique. It derived its strength from the combination of two discourses, one philosophical or religious, the other anthropological. The first discourse posited universal equality, grounded in nature, in the divine order of created being, or in the cumulative impact of both. In its radical formulations, the discourse of natural equality ruled out of court all hierarchical claims based on rank, gender, race, religion and culture. No one could claim privileges on account of tradition, gender, religious belief or skin color. No one was entitled to say that others were of lesser worth because they had different customs and manners. There certainly were limits, but these had to be rationally demonstrated. Pending the debate on such matters, equality had the benefit of the doubt. Measured against the yardstick of natural equality most of the prevailing justifications of European imperialism were found wanting. Even so, natural equality was not sufficient. It was too abstract to effectively nullify the ‘self-evident’ power of imperial common sense. That is where the anthropological turn comes into play. Questioning the naturalness and superiority of European civilization, or of any other great imperial power, it urged an intellectual engagement with the cultures of extra-European peoples that went further than the abstract acknowledgment of their humanity. What Anquetil Duperron says about the Eskimo, for instance, is not noble-savage mythology but the sober attestation that their adaptation to the arctic environment constitutes a valid way of life that is neither more nor less | |

[pagina 29]

| |

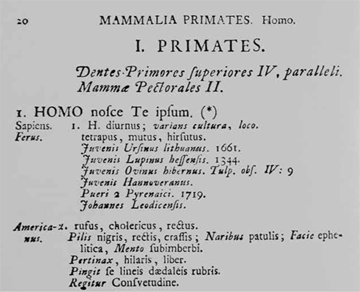

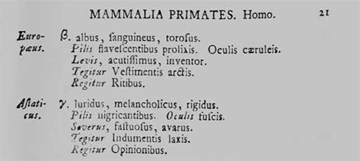

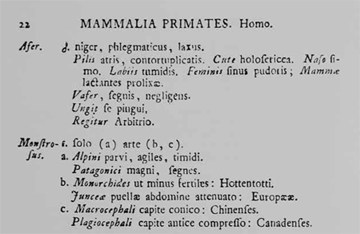

Carolus Linneaus, Description Homo sapiens, in: 10th edition Systema naturae (1758).

| |

[pagina 30]

| |

reasonable than what Europeans have accomplished in quite different circumstances. The anthropological turn stimulates an open-minded curiosity about other cultures, as in Bernard and Picart's review of the religious ceremonies of people worldwide. Instead of peremptory dismissal it calls for an emphatic understanding of the how and why of other cultures. That is not to say that it precludes a critical evaluation of other peoples' customs and beliefs, but it seeks to replace unthinking condemnation with well-informed and reasoned judgment.

It is the combination of a natural-rights ethics with the anthropological turn that accounts for the robustness of the global egalitarianism of Enlightenment anti-imperialism. A moderately positive appreciation of cultural diversity is wedded to a strong affirmation of the unity of human nature at an underlying level. Diderot's double yardstick of common welfare and individual utility cannot be applied when one is ignorant about the social arrangements people start from and the ecological and political challenges they are facing. Universal values, such as liberty and equality, are always applied in specific historical circumstances. To arrive at realistic and reasonable judgments, both sides of the equation must be taken into account. The upshot of Diderot's thesis that one cannot judge Tahiti by a European yardstick nor Europe by a Tahitian yardstick, is that no society or culture is beyond critique, but also that reasonable and sincere judgment always includes self-criticism. The most intractable issue of all, however, concerns the relationship of the anti-imperialist discourse outlined above with the unfolding truth of philosophical history. I use the expression ‘unfolding truth’ advisedly. According to the stadial theory of philosophical history, European ‘commercial civilization’ represented the future of the rest of humanity. However, the progression through the stages of history was also theorized as the ‘progress of the human mind’, a standing expression in Enlightenment historical terminology. Knowledge and power advanced in tandem. Kant boldly asserted that the ‘progress towards perfection’ inhered in human nature. It might falter and slow down for long periods, but it could never be entirely halted.Ga naar eindnoot72 Seen in that light, the progression of world history would ultimately result in global enlightenment. Raynal repeatedly affirmed that ‘reason’ would in due course put an end to all the wild superstitions and religious deliriums of the peoples of the world. In practical terms, that could only mean that Europe would - as Condorcet later announced - educate and enlighten the rest of the world. The future fulfillment of philosophical history thus bestowed a universal pedagogical authority on the European global vanguard. This view of history was most emphatically underwritten by the Radical Enlightenment, because it deemed all religious beliefs incompatible with the rule of reason. To the radicals, global Enlightenment was the inevitable corollary of the anticlerical struggle they waged at home. Diderot's anti-imperialism assumed as a matter of course that the Christianization of the rest of the world was part and parcel of European imperialism (let us recall that the Old Tahitian prophesied that the Fre- | |

[pagina 31]

| |

nch would be back, carrying the sword and the cross). It remains true, however, that in Enlightenment philosophical history, even in its most impeccably radical incarnations, the extra-European peoples have little agency. European expansion is the main vector of world history. It is here that I cannot agree with Jonathan Israel's impressive and admirable history of the Radical Enlightenment. Israel's discussion of the noble savage theme is a case in point. He invokes Spinoza, Bayle and Fontenelle as radicals who ‘laid the basis of a fully-fledged radical early-Enlightenment anti-imperialism’, and who ‘encouraged greater appreciation and more extensive study of primitive societies’. Israel quotes Nicolas Guedeville's vision of the noble savage as ‘un de ces hommes qui suivent le pur instinct de la nature’.Ga naar eindnoot73 Israel is surely right to draw our attention to the egalitarian effects of the radicals' vision of the ‘savages’ as he is also right to point to the use of the noble savage as a vehicle for a critique of European society, and to the categorical denial of a bio-racial hierarchy by the radicals. What he fails to discuss, however, is that the depiction of the culture of the savages as ‘natural’ also situated them at the dawn of human history. The customs of the savage are used as a moral mirror, but the real savages are already superseded by the subsequent course of history. They are still physically present in the world of the eighteenth century, but philosophically their time is over. Fontenelle, cited by Israel as a protagonist of early anti-imperialism, did not at all sing the praise of any noble savage, but asserted that the American savages could have equaled the cultural level of the ancient Greeks, if given the time. Writing more than two centuries after Columbus, Fontenelle and his readers knew full well that the ‘time’ for future autonomous development was precisely what the American Indians had been robbed of. Presenting a much stronger and far more explicit anti-imperialist agenda, Anquetil Duperron says precisely the same at the end of the eighteenth century. The Inca and the Aztecs, he contends, might have played a role comparable to that of Rome and China in Eurasian history, but the Spaniards annihilated their civilizations and thus destroyed the germs of future indigenous American progress.Ga naar eindnoot74 Natural equality and philosophical history are not easily disentangled. If humanity consisted of differentially endowed and inalterable biological races, the whole scheme of philosophical history would collapse. It is precisely because all humans are endowed with the same needs and capacities that a historical pattern of slower and faster development through the same ‘universal’ four stages becomes thinkable. Again, this observation applies with particular force to the Radical Enlightenment, because the radicals, denying all religious transcendence, had dismantled all extra-temporal Archimedean points. Consequently, they were compelled to argue their case exclusively in terms of the operation of cognitive and moral ideas within the confines of secular history. Natural equality provides them with a moral standpoint to criticize European imperialism, but it was also the anthropological bedrock of the mighty edifice of philosophical history. In that sense, the secularization of intellectual life and the increase of world-historical knowledge made the critique of imperialism at the same time more | |

[pagina 32]

| |

powerful and more difficult. What of global equality? What did it mean to assert the equality of all the inhabitants of the earth? To the Enlightenment mind, universal equality was both an abstract moral principle and a historical trend. As a moral principle it offered a foundation for the censure of European arrogance and greed. As a historical trend, it entailed that the non-European peoples would attain equality by coming to resemble those who ‘were already equal’; that is, by becoming like the Europeans. In the turbulent history of the last two centuries, this vision of becoming equal has gone under the names of ‘modernization’ and ‘development’. The economic vision underpinning it was grounded in political economy, one of the major Enlightenment discourses of inequality. In the second half of the eighteenth century, political economy boomed as never before. Raynal's enthusiastic encomium of commerce was part of larger trend in economic publishing.Ga naar eindnoot75 Development was, and still is, the goal of virtually all state-elites in the world. In terms of wealth and power, however, it has frequently assumed the shape of a receding target. This notion of becoming equal proved to be part and parcel of a global process of modernization dominated by Europe, and later ‘the West’. It is not enough (as Jonathan Israel does) to quote the egalitarian declarations and conclusions of the Enlightenment critics of imperialism. One must also examine their insertion and elaboration in the Enlightenment vision of society and history. Only then can we fully understand why so much of the critique of imperialism is impassionate and sincere, but also frequently exculpatory (‘they cannot help being savages’), mournful (‘history may obliterate them in the end’), and commanding (‘they must follow the path of reason, or else...’). The foregoing is, of course, written with the benefit of hindsight. To the men and women of the eighteenth century things were not so clear. To them, the scenario of philosophical history was probable, frequently also desirable, but by no means certain. In this connection, the coexistence of two philosophies of history in the eighteenth century is a tell-tale sign. One, in the long run the most powerful, was philosophical history, but the other, as we have seen, was the ancient vision of the rise and decline of empires. Let us recall that, next to Smith's Wealth of Nations, Robertson's History of America and Raynal's Histoire des Deux Indes, Gibbon's Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire was one of the most influential books of the late Enlightenment. Gibbon reminded his European readers - if they needed reminding - of the precariousness of all world empires, including the nascent European one. With the benefit of hindsight, the advance of Europe to world power may seem retrospectively inevitable, but to the contemporaries of Diderot and Gibbon the future course of history was probably less than self-evident. They were living in a world of weak and unreliable long-distance communication. Economic growth was conditioned by the pace of agricultural productivity, which according to Malthus was already approaching its limits in eighteenth-century England. Beyond these economic and logistic considerations there always lurked the dangerous imperial feedback on Europe itself. At times, Di- | |

[pagina 33]

| |

derot and Raynal were almost obsessed by the decivilizing effects of imperialism. The overseas Europeans, feared Raynal, were prone to turn into a new species of global barbarians. The metamorphosis of the overseas European, he observed, was a ‘strange phenomenon’.Ga naar eindnoot76 This was not a confident vision of boundless imperial expansion. It is true that Emmanuel Sieyès, who would become the most influential political thinker of the first phase of the French Revolution, declared in his notebooks (around 1780) that ‘the net product of the arts is unlimited’, but we may doubt whether even Sieyès realized the full revolutionary implications of his own words.Ga naar eindnoot77 To most eighteenth-century observers, the great leap in the productivity of agriculture that was to come in the early decades of the nineteenth century was well-nigh unthinkable. We should be careful not to project nineteenth-century accomplishments back into the Enlightenment. The eighteenth-century horizon of economic and technological expectations was limited and frequently somber. It gave the ancient critique of world empires a relevance that can easily escape us, accustomed as we are to see the Enlightenment as the scaffolding of modernity. Universal equality and the anthropological turn were powerful and valuable vehicles of anti-imperialism, but they should be judged in the context of the new Enlightenment ‘human science’ of which philosophical history was an integral part.Ga naar eindnoot78 In thinkers like Diderot and Anquetil Duperron, we can identify a subtext that leaves room for cultural diversity as a vital component of global equality, containing the germs of a vision of the future that was less constrained by the imperative of global enlightenment in the European mould. We should not, however, pretend that Spinoza, or the eighteenth-century radicals, already theorized the principles and concepts that we should adopt in today's global politics. Neither the economic and political nor the intellectual continuities between the eighteenth century and our time are sufficient to make that a feasible intellectual project. That is not to say that we can simply say good bye to the Enlightenment as we did to Aristotelian physics or the phlogiston theory of fire. A careful scrutiny of the tensions in Enlightenment anti-imperialism and its incipient theorizing of the global may help us to identify and come to grips with analogous tensions in our present-day controversies over global equality and cultural difference. In particular, it might enable us to see that global enlightenment does not need to be an all-or-nothing game. In some respects, such as rights and liberties, a more homogeneous world is probably desirable, but cultural uniformity across the board is an altogether different matter. Over the past two centuries, its relentless drive has destroyed the way of life of entire peoples, and in some cases the European modernization of the world resulted in the genocidal extermination of the very peoples it purported to ‘save’ from savagery and barbarism.Ga naar eindnoot79 In the eighteenth century, radical materialists, dualist philosophers (Cartesians or Kantians), as well as enlightened religious thinkers approached this problematic from different perspectives. The critique of imperialism was not a monopoly of the radical materialists. The Jansenist Anquetil Duperron and the Deistic post-protestant Immanuel Kant were as critical of European | |

[pagina 34]

| |

expansion as the materialist Diderot. As in the Enlightenment, so it carries on today. Contrary to radical secularist expectations, religious thought and, for example, Confucian philosophy continue to inspire numerous thinkers worldwide. Cultural and intellectual pluralism are a permanent feature of our globalizing world. The debates over these matters remain unresolved at the beginning of the twenty-first century. The legacy of the Enlightenment is a series of controversies that are ‘good to think with’. Final certainties and absolute truths are not to be had. |

|